Wayne Cochran

"Going Back to Miami"

On December 10, 1967, Otis Redding was killed in a plane crash just as his career was crossing over to a new audience in a big way. Otis was already considered one of the greatest soul singers in the business, but had yet to reach “Motown”-sized respect and payback. His audience was still primarily black. With the release of “Dock of the Bay” four months after his untimely demise, all of that would change.

A short time later, I was watching “Where the Action Is,” one of the few shows dedicated almost exclusively to rock and roll in the late sixties. Paul Revere, of Paul Revere & the Raiders fame, was the host. He introduced the next performer as one of Otis's closest and oldest friends and said “He'll be performing Otis Redding's big hit “Dock of the Bay” as a tribute. Here he is...Mr. Wayne Cochran!”

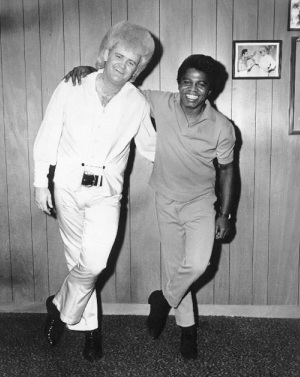

Cochran appeared on screen, an unsettling vision with the face and frame of a heavyweight pugilist. His pug nose and coiffed, seismic-pompadour, dyed a white-blonde were like James Brown's, only bigger—much bigger. Cochran was also a head taller than Brown and gave the impression of some fantastic Afro/Saxon hybrid. I watched with awe, unable to take my eyes off of him. Of the actual performance, I remember almost nothing, but my memory of the man is still vivid.

A few years later I moved to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida with my family and Wayne Cochran and the C.C. Riders were appearing at Bachelors III, a local nightclub that was partly owned by Joe Namath. Namath was, at the time, the hottest thing in football, having won the Super Bowl in 1969 as quarterback for the New York Jets. He was also a national sex symbol and budding actor, who had just finished making the biker flick “C.C. And Company” with co-star Ann Margret and Cochran in a supporting role.

Bachelors III was intended to be a showcase for the best musical talent in the business, featuring acts like Miles Davis, Blood Sweat and Tears, Lou Rawls and Buddy Rich, among others, who performed there on a weekly basis. Although I was too young to get in, my parents went after seeing Cochran and the C.C. Riders on Jackie Gleason's weekly television show. For my parents, the freaks, the hippies, the sheer electricity of it all offered an unforgettable front row seat to the counter culture. This wasn't Johnny Ray or even Elvis. This was a wild man, some audacious mixture of black soul man and white-trash hillbilly. According to their account, Cochran and company stormed the stage and did not relinquish it until all social barriers had fallen and the audience's world-view had been altered—if only for the night. For me, I could only imagine what had been denied me as the result of my age deficiency.

A short time later, I was watching “Where the Action Is,” one of the few shows dedicated almost exclusively to rock and roll in the late sixties. Paul Revere, of Paul Revere & the Raiders fame, was the host. He introduced the next performer as one of Otis's closest and oldest friends and said “He'll be performing Otis Redding's big hit “Dock of the Bay” as a tribute. Here he is...Mr. Wayne Cochran!”

Cochran appeared on screen, an unsettling vision with the face and frame of a heavyweight pugilist. His pug nose and coiffed, seismic-pompadour, dyed a white-blonde were like James Brown's, only bigger—much bigger. Cochran was also a head taller than Brown and gave the impression of some fantastic Afro/Saxon hybrid. I watched with awe, unable to take my eyes off of him. Of the actual performance, I remember almost nothing, but my memory of the man is still vivid.

A few years later I moved to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida with my family and Wayne Cochran and the C.C. Riders were appearing at Bachelors III, a local nightclub that was partly owned by Joe Namath. Namath was, at the time, the hottest thing in football, having won the Super Bowl in 1969 as quarterback for the New York Jets. He was also a national sex symbol and budding actor, who had just finished making the biker flick “C.C. And Company” with co-star Ann Margret and Cochran in a supporting role.

Bachelors III was intended to be a showcase for the best musical talent in the business, featuring acts like Miles Davis, Blood Sweat and Tears, Lou Rawls and Buddy Rich, among others, who performed there on a weekly basis. Although I was too young to get in, my parents went after seeing Cochran and the C.C. Riders on Jackie Gleason's weekly television show. For my parents, the freaks, the hippies, the sheer electricity of it all offered an unforgettable front row seat to the counter culture. This wasn't Johnny Ray or even Elvis. This was a wild man, some audacious mixture of black soul man and white-trash hillbilly. According to their account, Cochran and company stormed the stage and did not relinquish it until all social barriers had fallen and the audience's world-view had been altered—if only for the night. For me, I could only imagine what had been denied me as the result of my age deficiency.

Gleason, who lived in Ft. Lauderdale, caught his act at a local club called “The Barn” where Wayne would swing from the rafters and generally create mayhem with what was easily one of the deadliest bands around. It featured a who's who of local jazz, rock and soul talent, including a young unknown genius of the bass named Jaco Pastorious. With a few appearances on national television under his belt, Wayne Cochran became one of the most sought after singers in the business, leading to gigs in Vegas, television and film.

By the early seventies, the pompadour was gone, replaced by shoulder length white-blonde hair that was slightly less jarring to the senses and more in keeping with the changing youth culture. The clothes were blue-jean, American-flag from head to toe, which, at the time, was interpreted as un-American—since American flags were to be saluted, not worn. Having an American flag patch on your behind, was, for social dissidents, a backlash against American foreign policy in general and Vietnam in particular. To the older generation, it was seen as something akin to treason.

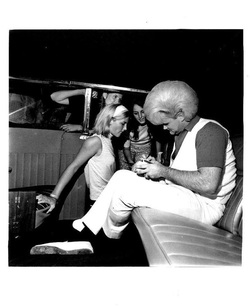

More than Cochran's stage appearance changed as well, he went from soul-revue, chitlin'-circuit act (that's what the C.C. Rider stood for) to rock and soul-biker-hippie front man. He rode the bus with his band across endless gigs and one-nighters, taking advantage of the open doors that celebrity had made possible. If that meant not sleeping, that was the price to be paid for fame—fueled by amphetamines and cocaine, with downers at the end of the night in an attempt at sleep. What sleep there was came sitting upright on a bus. (Duke Ellington, the godfather of all jazz musicians slept in an upright position even in the most comfortable bed after spending his life on the road.) For Cochran and crew it was no different.

A few years later, Wayne and the C.C. Riders were appearing along with the original Drifters, minus Ben E. King, at the “Seven Seas Lounge” which was on Miami Beach. North Beach was the place to be, then. South Beach, remarkably, had been reduced to a blighted neighborhood following the 1960s. By the 1970s the once modern paradise became known as “God's waiting room.”

Beachfront, Art Deco masterpieces were turned into cheap retirement homes for the severely elderly. As South Beach waited for revival, the action moved northward and the Seven Seas Lounge, with its futuristic look and neon lighting was a hipster's paradise. So, we quickly made our plans to see the man and his band in action.

We showed up ready to be lifted on high, first by a polished set from the Drifters, and then by Wayne Cochran and the C.C. Riders. After the Drifters set ended, the band, sans Cochran, took the stage and managed to rock and swing like a symphonious dynamo, probably the best R&B/rock band that I've seen before or since. Then the man was introduced and proceeded to mesmerize and cauterize the crowd, part James Brown, part Hell's Angels-rocker, driving the band relentlessly, without ever losing the groove. It was the kind of performance that needed to be seen as well as heard. The kind that didn't easily lend itself to the recording process, which is probably why so few of his records actually got close to his live shows. But, it was more than smoke and mirrors. It was the airtight musicianship, with a band that was run like a machine and a front man that had spent years honing his craft in clubs performing for unforgiving white and black audiences from Harlem to Tobacco Road.

By the early seventies, the pompadour was gone, replaced by shoulder length white-blonde hair that was slightly less jarring to the senses and more in keeping with the changing youth culture. The clothes were blue-jean, American-flag from head to toe, which, at the time, was interpreted as un-American—since American flags were to be saluted, not worn. Having an American flag patch on your behind, was, for social dissidents, a backlash against American foreign policy in general and Vietnam in particular. To the older generation, it was seen as something akin to treason.

More than Cochran's stage appearance changed as well, he went from soul-revue, chitlin'-circuit act (that's what the C.C. Rider stood for) to rock and soul-biker-hippie front man. He rode the bus with his band across endless gigs and one-nighters, taking advantage of the open doors that celebrity had made possible. If that meant not sleeping, that was the price to be paid for fame—fueled by amphetamines and cocaine, with downers at the end of the night in an attempt at sleep. What sleep there was came sitting upright on a bus. (Duke Ellington, the godfather of all jazz musicians slept in an upright position even in the most comfortable bed after spending his life on the road.) For Cochran and crew it was no different.

A few years later, Wayne and the C.C. Riders were appearing along with the original Drifters, minus Ben E. King, at the “Seven Seas Lounge” which was on Miami Beach. North Beach was the place to be, then. South Beach, remarkably, had been reduced to a blighted neighborhood following the 1960s. By the 1970s the once modern paradise became known as “God's waiting room.”

Beachfront, Art Deco masterpieces were turned into cheap retirement homes for the severely elderly. As South Beach waited for revival, the action moved northward and the Seven Seas Lounge, with its futuristic look and neon lighting was a hipster's paradise. So, we quickly made our plans to see the man and his band in action.

We showed up ready to be lifted on high, first by a polished set from the Drifters, and then by Wayne Cochran and the C.C. Riders. After the Drifters set ended, the band, sans Cochran, took the stage and managed to rock and swing like a symphonious dynamo, probably the best R&B/rock band that I've seen before or since. Then the man was introduced and proceeded to mesmerize and cauterize the crowd, part James Brown, part Hell's Angels-rocker, driving the band relentlessly, without ever losing the groove. It was the kind of performance that needed to be seen as well as heard. The kind that didn't easily lend itself to the recording process, which is probably why so few of his records actually got close to his live shows. But, it was more than smoke and mirrors. It was the airtight musicianship, with a band that was run like a machine and a front man that had spent years honing his craft in clubs performing for unforgiving white and black audiences from Harlem to Tobacco Road.

About a decade later, I finally met the man in person. He'd given up the road and the drugs, become a Christian pastor and radically changed his life. But, you could still see the old performer just beneath the surface, held in check, if ever so slightly, working hard to never give the devil an opening. The competitor was still there, the gravelly voice, the fiery, primal artiste. I spent a couple of years playing with his new band, listening to him teach, watching him perform. He was, like all artists, an amalgam of his past. Of all the things he was born into and all the things he chose to be. He was still the guy from Tobacco Road—the white-trash kid singing in black clubs for black patrons. He was also an intelligent and studious man, with a love of reading and a deep urge to teach anyone who would listen.

Eventually, I left the fold, but I returned a few years later to play at his 50th birthday party. I can still remember laying into a hot bluesy solo and watching Wayne crank his head and lift his eyes to hear and see where that sound was coming from. I had clearly gotten his attention. It wasn't much, but it was high enough praise from one of the toughest sons of bitches in show business.

For me, Wayne is living proof that there is redemption for all who ask—a fresh start for a willing heart. He still preaches every Sunday and every Wednesday at his church in Miami. You can hear him for free, still singing and still swinging from the rafters—if not literally, he continues to lift his hands and eyes upward nonetheless.

Mark Magula

Eventually, I left the fold, but I returned a few years later to play at his 50th birthday party. I can still remember laying into a hot bluesy solo and watching Wayne crank his head and lift his eyes to hear and see where that sound was coming from. I had clearly gotten his attention. It wasn't much, but it was high enough praise from one of the toughest sons of bitches in show business.

For me, Wayne is living proof that there is redemption for all who ask—a fresh start for a willing heart. He still preaches every Sunday and every Wednesday at his church in Miami. You can hear him for free, still singing and still swinging from the rafters—if not literally, he continues to lift his hands and eyes upward nonetheless.

Mark Magula