American Heritage New Illustrated History of the United States

In 1963, I was ten years old. I still vividly remember television ads for the American Heritage New Illustrated History of the United States. Imagine that, kids, TV ads for a set of illustrated books on American history! No DVDs, no music or interactive graphic displays, just books with pictures and text. The books were sold at grocery stores (in my case, Publix) and it was Publix’s ads that I saw. Being an avid reader from the age of five, my ten-year-old heart raced at the thought of devouring these heavily-illustrated histories. Imagine my joy when, on Christmas morning, I found all sixteen volumes under the Christmas tree!

As I write this, I realize that this makes incredibly hip me sound like some kind of ancient geek. Yo, what can I say, baby? I likes me some his-to-ry!

The books were read and re-read by my younger siblings and me throughout our childhood. Together with a myriad of “biographies of great Americans,” these books fed my interest in our nation and its history—an interest that continues to this day.

A few years ago, I had a number of immigrants working for me in an engineering firm. Some of them inquired of me as to how they might best study American history, since it was something they were interested in both as a general topic of interest and, more particularly, as a necessary part of their becoming an American citizen. I remembered these books and brought them to the office. I brought them because the books were written at what was, I suppose, an eighth-grade level, as measured in 1963. Based on what I’ve seen in American schools these days, I would now put them at a college freshman level (Oh, how we’ve dumbed down academics in this country over the last forty years!). Anyway, these young engineers, for whom English was a second language, found the books to be at an appropriate, and very accessible, level.

American Heritage magazine, the creator of these books, has, for over fifty years, sought to be a popularizer of American history—if not necessarily for the masses, at least for the apirational middle class. However, in 1963, they had only been around for nine years. An earlier magazine, American Heritage: A Journal of Community History, had existed in a more subdued form from 1947 to 1954 but the modern magazine, known for its slick, colorful illustrations, was produced with help from former Time-Life magazine personnel commencing with the December 1954 edition. The magazine was founded under the guidance of Allan Nevins, a well-regarded Civil War historian who had assembled a group of academics to promote American history to the general population. Mr. Nevins, although not necessarily a populist, believed that the American people needed to know their own history and sought to wrest control of our nation’s historical narrative from the arid grip of academia. He successfully navigated the change from an academic publication to a more popular magazine and, as far as I can tell, remained associated with American Heritage until his death in 1971.

As it happened, American Heritage magazine decided to publish this set of sixteen volumes for young readers and hired one of the great historians of the era, Robert G. Athearn, of the University of Colorado, to assemble the books. Mr. Athearn (1914-1988) was a well-regarded historian known most for his histories of the West, which were written in a particularly engaging, accessible style. It was this talent for bringing together great historical themes with interesting insights into the lives of individuals that made Mr. Athearn’s histories popular with both the general public and academics. From my vantage point, both as a ten-year-old boy and as a much older adult, he was the right man for the job. These volumes are a brilliant summary of the United States of America, from the arrival of the first European explorers in the New World through the early years of the space program (A revised edition, released in 1988, apparently adds more current history, including the Viet Nam War, the moon landing, Watergate, etc.).

As I re-read these books, I am struck by the confidence in our “manifest destiny” that permeates the text. It is easy to forget now that the people who contributed to the creation of these volumes had been on the winning side in World War II, successfully beating back barbarism for another generation in the west, had overcome extreme economic depression, and had established a dominant culture on the world stage. The confidence expressed in these volumes is refreshing at a time now when even many of our own people assume malevolent, ulterior motives for our government’s every action.

Perhaps a sign of the times was best illustrated by the choice of author for the first volume’s foreword—President John F. Kennedy. Tragically, his foreword was written mere months before he was struck down in November, 1963.

As I re-read these books, I am struck by the confidence in our “manifest destiny” that permeates the text. It is easy to forget now that the people who contributed to the creation of these volumes had been on the winning side in World War II, successfully beating back barbarism for another generation in the west, had overcome extreme economic depression, and had established a dominant culture on the world stage. The confidence expressed in these volumes is refreshing at a time now when even many of our own people assume malevolent, ulterior motives for our government’s every action.

Perhaps a sign of the times was best illustrated by the choice of author for the first volume’s foreword—President John F. Kennedy. Tragically, his foreword was written mere months before he was struck down in November, 1963.

President Kennedy established, as it were, the intent of the books in his opening paragraph, “There is little that is more important for an American citizen to know than the history and traditions of his country. Without such knowledge, he stands uncertain and defenseless before the world, knowing neither where he has come from nor where he is going. With such knowledge, he is no longer alone but draws a strength far greater than his own from the cumulative experience of the past and a cumulative vision of the future.”

No doubt there was a time when such sentiments would have been accepted as obvious. However, it is no longer obvious today. In an age of ever-increasing societal stratification, with claims of victimhood from every corner, such a straightforward statement of intent is not often asserted so easily. The simple phrase “traditions of his country,” for example, would today be attacked by feminists for being chauvinistically male oriented, would be assailed by minorities as being reflective of a white, Eurocentric vantage point, and would be regretted by limp-wristed Northeastern Liberals as being “hurtful” of others. May God have mercy on us all!

No doubt many of those who would object to President Kennedy’s statement were children in 1963. Like me, they read these books and internalized lessons from them. However, also like me, they grew up in a world that offered many lessons to the contrary of the noble ideals expressed in President Kennedy’s foreword or, indeed, in the histories themselves.

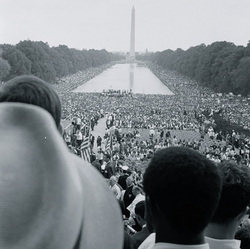

To defend Baby Boomers a bit, I submit that there was a profound cognitive dissonance between the noble ideals contained in histories written at the time and the reality of the civil rights movement that so consumed our formative years. A country with a dominant population and culture that viewed itself as the defender of freedom around the world had largely turned a blind eye to racial injustice at home. This moral rot at the center of our nation was exacerbated by a personal allegiance to the “appearance of righteousness” rather than actual righteousness. For example, growing up in the rural South, everyone but “white trash,” of which there was less than you might imagine, attended church religiously. However, the other six days of the week, many of those devout churchgoers lived anything but a godly life. The faith they claimed to hold dear was actually nothing more than a social obligation, unmatched by any moral obligation such as “love your neighbor as yourself.”

No doubt there was a time when such sentiments would have been accepted as obvious. However, it is no longer obvious today. In an age of ever-increasing societal stratification, with claims of victimhood from every corner, such a straightforward statement of intent is not often asserted so easily. The simple phrase “traditions of his country,” for example, would today be attacked by feminists for being chauvinistically male oriented, would be assailed by minorities as being reflective of a white, Eurocentric vantage point, and would be regretted by limp-wristed Northeastern Liberals as being “hurtful” of others. May God have mercy on us all!

No doubt many of those who would object to President Kennedy’s statement were children in 1963. Like me, they read these books and internalized lessons from them. However, also like me, they grew up in a world that offered many lessons to the contrary of the noble ideals expressed in President Kennedy’s foreword or, indeed, in the histories themselves.

To defend Baby Boomers a bit, I submit that there was a profound cognitive dissonance between the noble ideals contained in histories written at the time and the reality of the civil rights movement that so consumed our formative years. A country with a dominant population and culture that viewed itself as the defender of freedom around the world had largely turned a blind eye to racial injustice at home. This moral rot at the center of our nation was exacerbated by a personal allegiance to the “appearance of righteousness” rather than actual righteousness. For example, growing up in the rural South, everyone but “white trash,” of which there was less than you might imagine, attended church religiously. However, the other six days of the week, many of those devout churchgoers lived anything but a godly life. The faith they claimed to hold dear was actually nothing more than a social obligation, unmatched by any moral obligation such as “love your neighbor as yourself.”

The hypocrisy inherent in these attitudes seems to have had two primary effects upon my generation. First, it caused many to question the value and truthfulness of their Christian faith. Second, it caused them to distrust the authority figures, parents, teachers and government officials that ruled over them.

The tragedy of the first part is this: God was rejected because His creation, man, failed. This is an unreasonable position in that it assumes we can, or even have the right to, judge God. If there is, in fact, a God who created everything and who gave that creation to us, along with a free will, then He is the creator and we are merely part of His creation. As such, who are we to declare Him a failure because He permitted mankind to choose its path and it has often chosen poorly?

The tragedy of the second part is, perhaps, more understandable. Although all children would like for their parents and other authority figures to be always commendable and correct, it is a sad fact of life that every human being is fallible. Even the most loving and well-intentioned parents will inevitably disappoint their children at some point in their lives. Sadly, many of us encountered parents, police, teachers and others who not only failed to live up to our nation’s ideals, but who never even tried to do so.

One might conclude then that the American Heritage histories are of little value, based on the foregoing statements. Au contraire, these histories of our nation remain classic works, well worth reading by Baby Boomers and their children and grandchildren. What is often missed in this era of societal conflict, of political argument and personal attack, is this: in spite of our many disagreements, Baby Boomers remain largely united in their love of country and confidence in the ideals of our nation, as expressed in our formative documents and as lived by our forebearers. Regardless of color, regardless of social status, most of this generation is keenly aware of the significance of our nation and its success on the world stage.

Although the Baby Boom generation has much to answer for as a consequence of their often extreme self centeredness; grotesque levels of governmental and personal debt, a culture of easy marriage and easy divorce, casual cynicism towards authority, etc., they, at least, were taught the fundamentals of civics in school and had American history drilled into them. Sadly, this can no longer be assumed as a given for our children and their children.

This is not to denigrate those born in the last thirty years but, rather, to note the value of an appreciation for the struggles of those who came before. Many millions worked to create and maintain a society that exemplifies the noble ideals expressed in our Declaration of Independence, Constitution and Bill of Rights. Knowing from whence we came allows us to evaluate where we are and make adjustments based on the experience of ourselves and our ancestors—treasuring those verities which have stood the test of time and discerning that which is merely a distraction of the moment.

Having recently read portions of the American Heritage New Illustrated History of the United States again for the first time in many years, I was amazed by the easy way in which great themes were explained. I marvel that these works were designed for children. For example, in the first volume, The New World, Mr. Athearn briefly describes the conditions existing in the Old World of Western Europe that made exploration of the New World possible. The descriptions are brief, penetrating and wise. He then contrasts the relative success of the English colonies with those of the Spanish, noting that, “Spanish colonial administration was characterized by extreme control, which helps account for the fact that Spain had colonies in America longer than most of its European neighbors. It also explains in part why once the colonies of Spain had freed themselves, they had difficulty in establishing stable, self-sustaining governments. So long a time under such rigid and centralized control killed much of the initiative seen in the English colonies, where a measure of self-government existed from the outset.”

In this brief passage Mr. Athearn summarizes a critical element of our nation’s strength, government for and by the people, and contrasts it with the more totalitarian, centralized system of Spain. However, it could have just as easily been a critique of the Soviet Union’s system versus ours during the Cold War—a war that was in full swing in 1963. To his credit, Mr. Athearn leaves it to his readers to make that association if they choose. He merely continues with the history of the American colonies.

As I noted above, I marvel that these books were written for children. I asked my daughter, who recently graduated from the University of Miami, if any of her teachers had ever made such observations on American history and she said, “No.” While she is only one product of South Florida’s public schools—and an honor student at that—her surprise at this insight being provided in a so-called children’s history was palpable. She said that she had never heard this taught in class nor discussed with her friends.

Of course, being her dad, I pointed out to her that I had tried to get her to read these books many times over the years, only to be met with, “Oh, Dad!” from her! But I digress…

Hopefully, I’ve made the case for the value of knowing our nation’s history, for teaching our children (some of mine listened!), and for the quality of this series of histories. A casual search online revealed that both the 1963 and 1988 editions of the American Heritage New Illustrated History of the United States are available at very affordable prices. If you have a “reader” in the household, get them these books, read them together and discuss them, it will be rewarding for you and your child. We, as parents, are responsible for the next generation. If we present our nation’s history to our children, we will help to instill our nation’s values in them, will demonstrate our own appreciation for those values, and may even find a new resolve to do as President Kennedy so famously said in his inaugural speech, “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”

Thomas A. Hall

The tragedy of the first part is this: God was rejected because His creation, man, failed. This is an unreasonable position in that it assumes we can, or even have the right to, judge God. If there is, in fact, a God who created everything and who gave that creation to us, along with a free will, then He is the creator and we are merely part of His creation. As such, who are we to declare Him a failure because He permitted mankind to choose its path and it has often chosen poorly?

The tragedy of the second part is, perhaps, more understandable. Although all children would like for their parents and other authority figures to be always commendable and correct, it is a sad fact of life that every human being is fallible. Even the most loving and well-intentioned parents will inevitably disappoint their children at some point in their lives. Sadly, many of us encountered parents, police, teachers and others who not only failed to live up to our nation’s ideals, but who never even tried to do so.

One might conclude then that the American Heritage histories are of little value, based on the foregoing statements. Au contraire, these histories of our nation remain classic works, well worth reading by Baby Boomers and their children and grandchildren. What is often missed in this era of societal conflict, of political argument and personal attack, is this: in spite of our many disagreements, Baby Boomers remain largely united in their love of country and confidence in the ideals of our nation, as expressed in our formative documents and as lived by our forebearers. Regardless of color, regardless of social status, most of this generation is keenly aware of the significance of our nation and its success on the world stage.

Although the Baby Boom generation has much to answer for as a consequence of their often extreme self centeredness; grotesque levels of governmental and personal debt, a culture of easy marriage and easy divorce, casual cynicism towards authority, etc., they, at least, were taught the fundamentals of civics in school and had American history drilled into them. Sadly, this can no longer be assumed as a given for our children and their children.

This is not to denigrate those born in the last thirty years but, rather, to note the value of an appreciation for the struggles of those who came before. Many millions worked to create and maintain a society that exemplifies the noble ideals expressed in our Declaration of Independence, Constitution and Bill of Rights. Knowing from whence we came allows us to evaluate where we are and make adjustments based on the experience of ourselves and our ancestors—treasuring those verities which have stood the test of time and discerning that which is merely a distraction of the moment.

Having recently read portions of the American Heritage New Illustrated History of the United States again for the first time in many years, I was amazed by the easy way in which great themes were explained. I marvel that these works were designed for children. For example, in the first volume, The New World, Mr. Athearn briefly describes the conditions existing in the Old World of Western Europe that made exploration of the New World possible. The descriptions are brief, penetrating and wise. He then contrasts the relative success of the English colonies with those of the Spanish, noting that, “Spanish colonial administration was characterized by extreme control, which helps account for the fact that Spain had colonies in America longer than most of its European neighbors. It also explains in part why once the colonies of Spain had freed themselves, they had difficulty in establishing stable, self-sustaining governments. So long a time under such rigid and centralized control killed much of the initiative seen in the English colonies, where a measure of self-government existed from the outset.”

In this brief passage Mr. Athearn summarizes a critical element of our nation’s strength, government for and by the people, and contrasts it with the more totalitarian, centralized system of Spain. However, it could have just as easily been a critique of the Soviet Union’s system versus ours during the Cold War—a war that was in full swing in 1963. To his credit, Mr. Athearn leaves it to his readers to make that association if they choose. He merely continues with the history of the American colonies.

As I noted above, I marvel that these books were written for children. I asked my daughter, who recently graduated from the University of Miami, if any of her teachers had ever made such observations on American history and she said, “No.” While she is only one product of South Florida’s public schools—and an honor student at that—her surprise at this insight being provided in a so-called children’s history was palpable. She said that she had never heard this taught in class nor discussed with her friends.

Of course, being her dad, I pointed out to her that I had tried to get her to read these books many times over the years, only to be met with, “Oh, Dad!” from her! But I digress…

Hopefully, I’ve made the case for the value of knowing our nation’s history, for teaching our children (some of mine listened!), and for the quality of this series of histories. A casual search online revealed that both the 1963 and 1988 editions of the American Heritage New Illustrated History of the United States are available at very affordable prices. If you have a “reader” in the household, get them these books, read them together and discuss them, it will be rewarding for you and your child. We, as parents, are responsible for the next generation. If we present our nation’s history to our children, we will help to instill our nation’s values in them, will demonstrate our own appreciation for those values, and may even find a new resolve to do as President Kennedy so famously said in his inaugural speech, “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”

Thomas A. Hall