Judy Garland "Soul Singer"

The term “Soul Singer” has, for me, always meant something more than just another R&B singer, singing with a Gospel feel; although, that would be a reasonable enough definition. There have been more than a few great soul singers that never sang R&B or Gospel music. The two forms combined are generally considered necessary to have “True” soul music. As is often the case with words applied to living, breathing things, a single rigid definition will never do.

Years ago, I remember reading an interview with Lonnie Mack, the one-of-a-kind guitarist for whom the term “Roadhouse Rocker” seems to have been invented. He also happened to be a much underrated singer who tackled everything from early Rock and Roll to Country music—and even Otis Redding-style soul ballads—before anyone knew who Otis was. When he was asked who he thought of, when he thought of great soul singers, without hesitation he said “George Jones” and then followed with, “If George Jones ain’t a soul singer, I’ll kiss your ass!” George may not have fit the traditional definition of the term, but he more than fit its deeper meaning.

For my money, Judy Garland was a soul-singer—and I’m not sure that anyone, not even Ray Charles or Aretha Franklin, were any better. Few performers had her chops, and fewer still could begin to match her musical range. From swinging big band tunes to maudlin movie music, she made it all sound good. She could sing the same ballad two or three times a night, over a thousand nights and still break your heart.

Like most great musicians, she had an intuitive sense about words, melody and rhythm. If the lyric had the potential for a deeper subtext, she found it. If it lacked any meaningful subtext, she found it anyway. As is the case with all great singers, she didn’t merely interpret what was written. She possessed it, embodied it, and breathed her life into its shell. That’s how a few chords, a melody and rhythm become “Standards.” The standard by which other singers and songs are held to.

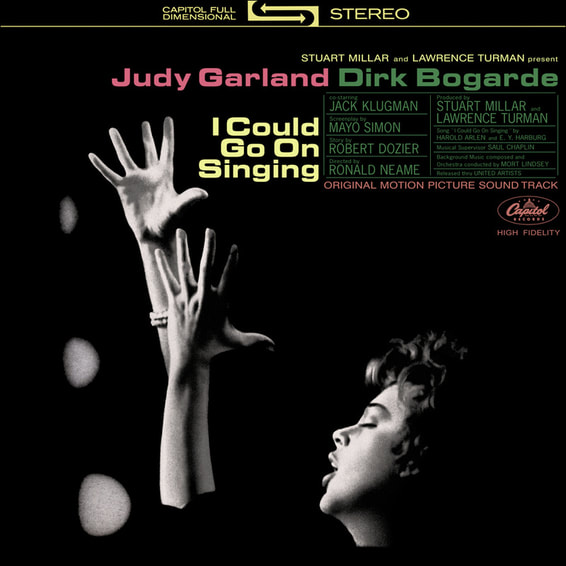

Along the way, great performers carve out a repertoire, by taking a body of songs and turning them into their personal property. There are “Sinatra Songs,” music that is so closely associated with the man that it can only be done in tribute. This was no less true of Judy. "The Man That Got Away," "Over the Rainbow," and "The Trolley Song" are just a few of the songs that are “Garland Songs.”

Years ago, I remember reading an interview with Lonnie Mack, the one-of-a-kind guitarist for whom the term “Roadhouse Rocker” seems to have been invented. He also happened to be a much underrated singer who tackled everything from early Rock and Roll to Country music—and even Otis Redding-style soul ballads—before anyone knew who Otis was. When he was asked who he thought of, when he thought of great soul singers, without hesitation he said “George Jones” and then followed with, “If George Jones ain’t a soul singer, I’ll kiss your ass!” George may not have fit the traditional definition of the term, but he more than fit its deeper meaning.

For my money, Judy Garland was a soul-singer—and I’m not sure that anyone, not even Ray Charles or Aretha Franklin, were any better. Few performers had her chops, and fewer still could begin to match her musical range. From swinging big band tunes to maudlin movie music, she made it all sound good. She could sing the same ballad two or three times a night, over a thousand nights and still break your heart.

Like most great musicians, she had an intuitive sense about words, melody and rhythm. If the lyric had the potential for a deeper subtext, she found it. If it lacked any meaningful subtext, she found it anyway. As is the case with all great singers, she didn’t merely interpret what was written. She possessed it, embodied it, and breathed her life into its shell. That’s how a few chords, a melody and rhythm become “Standards.” The standard by which other singers and songs are held to.

Along the way, great performers carve out a repertoire, by taking a body of songs and turning them into their personal property. There are “Sinatra Songs,” music that is so closely associated with the man that it can only be done in tribute. This was no less true of Judy. "The Man That Got Away," "Over the Rainbow," and "The Trolley Song" are just a few of the songs that are “Garland Songs.”

Like Sinatra, she was never really a jazz singer. Both were essentially Pop singers, or popular interpreters of “The Great American Songbook” during the music’s Golden Age when Jazz was king. She didn't improvise much with the melody or alter the rhythm. But could she swing, and she always sold the song's narrative with the artistry of a master thespian, which she was. The sheer beauty and power of her voice did the rest. It was a singular instrument, shaped by life and flush with interpretive gifts.

Even at the tender age of fifteen you can hear it; the chops, the range, the full, rich voice, it’s all there in her version of “Over the Rainbow.” She takes the Harold Arlen tune and imbues it with a deep sense of longing—which the lyric demands—giving a definitive performance. Judy turned Arlen’s song into a classic. And then made the song essentially untouchable for any other singer. Almost 75 years later that still remains true.

That she gave the performance at all is accomplishment enough, it certainly would be for most singers. That she gave it at fifteen is another thing altogether.

Thank God for the numerous clips of Judy singing on TV and in films, including some from her own short-lived television show. A substantial number of her recordings are equally good. Especially, the live recordings where she had an audience to emotionally work off of.

Her best performances are as good as anything by Pavarotti, Sinatra or Billie Holiday—and she was never less than good. With the definition of “Good” being redefined according to her enormous talent, which deserves its own unique classification. These are the things Judy Garland should be remembered for--not the drugs or the failed marriages.

Too often, we celebrate the tragic elements of an artist’s life, almost more than their accomplishments. Tragedy and hardship, after all, can shape who we are in a way that almost nothing else does. But there has to be an indomitable will to not only survive, but to excel at the highest possible level. And, in the end, it’s the sheer joy found in their artistry that makes us care at all.

As selfish as that sounds, it makes a kind of sense. With life swarming abundantly everywhere around us, its commonness can blur the relevance of the individual, which may seem unfair. Only if we are compelled to sit up and take notice, do we tend to acknowledge it at all. When the acclaim is so overwhelming that we have to find new ways to talk about it in order to do it justice, then, we know that it represents something bigger. It’s when we can see ourselves, and “Our” stories being told through a unique talent and a common lens, that a kind of universal truth begins to emerge.

The artist that can do that will live forever.

Judy, like a small handful of performers, was a standard-bearer. Her life may have, in some ways, been tragic, but her talent was anything but. If the only time she really came alive was when she was on stage, it may be that she simply needed a stage, a very large stage, on which to tell her story.

For the rest of us listening, anything less would have been the real tragedy.

Mark Magula

Even at the tender age of fifteen you can hear it; the chops, the range, the full, rich voice, it’s all there in her version of “Over the Rainbow.” She takes the Harold Arlen tune and imbues it with a deep sense of longing—which the lyric demands—giving a definitive performance. Judy turned Arlen’s song into a classic. And then made the song essentially untouchable for any other singer. Almost 75 years later that still remains true.

That she gave the performance at all is accomplishment enough, it certainly would be for most singers. That she gave it at fifteen is another thing altogether.

Thank God for the numerous clips of Judy singing on TV and in films, including some from her own short-lived television show. A substantial number of her recordings are equally good. Especially, the live recordings where she had an audience to emotionally work off of.

Her best performances are as good as anything by Pavarotti, Sinatra or Billie Holiday—and she was never less than good. With the definition of “Good” being redefined according to her enormous talent, which deserves its own unique classification. These are the things Judy Garland should be remembered for--not the drugs or the failed marriages.

Too often, we celebrate the tragic elements of an artist’s life, almost more than their accomplishments. Tragedy and hardship, after all, can shape who we are in a way that almost nothing else does. But there has to be an indomitable will to not only survive, but to excel at the highest possible level. And, in the end, it’s the sheer joy found in their artistry that makes us care at all.

As selfish as that sounds, it makes a kind of sense. With life swarming abundantly everywhere around us, its commonness can blur the relevance of the individual, which may seem unfair. Only if we are compelled to sit up and take notice, do we tend to acknowledge it at all. When the acclaim is so overwhelming that we have to find new ways to talk about it in order to do it justice, then, we know that it represents something bigger. It’s when we can see ourselves, and “Our” stories being told through a unique talent and a common lens, that a kind of universal truth begins to emerge.

The artist that can do that will live forever.

Judy, like a small handful of performers, was a standard-bearer. Her life may have, in some ways, been tragic, but her talent was anything but. If the only time she really came alive was when she was on stage, it may be that she simply needed a stage, a very large stage, on which to tell her story.

For the rest of us listening, anything less would have been the real tragedy.

Mark Magula