Jury Duty

A number of years ago I had the misfortune of having been chosen for jury duty. Thankfully, it was a one-day trial dealing with a drunk driver. No one was injured, it was a case of a young guy having a bit too much to drink on his birthday and getting caught as he attempted to make his way home while swerving down the road. All of which was captured on tape by a policeman’s camera.

The accused repeatedly failed every part of the sobriety test, and even admitted to the officer that he had too much to drink. A case doesn't get much more open and shut than that. And yet, with his guilt a mere afterthought, he showed up for his trial with an attorney who pleaded his actions as a forgivable slight. After all, hasn't everyone, at one time or the other, pushed the boundaries of the law in equally small ways, but not gotten caught? What harm was done? Clearly he was sorry—and he wasn't really all that drunk anyway. Maybe the cop was a tad overzealous, a well-meaning but overeager legalist with an itchy ticket finger.

As the presentation portion of the trial came to an end, we were sent off to uphold our part of the bargain and do justice, to find the cold, hard truth. But then, something happened. The words of the defending attorney began to ring deep within the recesses of the jury’s consciousness. The empathetic impulses of the men and women who had been carefully chosen on the basis of just such sympathies began to have second thoughts—it was at this point, that the justifications began to flow like a river. The “maybes” and the “what ifs” took precedence over the facts, and with their own distant sense of guilt acting as a catalyst, some on the jury began to reinterpret the evidence.

Choosing a jury is a game of oneupmanship. The defense attempts to stack the deck of personality types in their favor and the prosecution does likewise, with justice as the remote, but ultimate goal. Inevitably, if the attorneys are more or less equally clever, there will be an uneasy compromise. With neither side having an unfair advantage, it could be seen as a case of mutual competence, or incompetence in some cases, making for a level playing field.

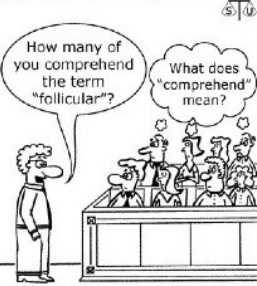

Both sides choose based on demographics. Race, sex, class, education, political affiliation are all factored when picking a "discriminating" juror--with all other tactical advantages being utilized judiciously. We potential jurors were sized up and down, with questions stated, but carefully phrased in a coded appeal to our sympathies, a verbal Rorschach Test intended to separate the wheat from the chaff.

In reality, legal trials aren't a search for the truth as much as a game played for money, no different than any other game, like baseball, or politics. Justice is the goal, at least abstractly, and everyone gets paid; judge, attorneys and even the jury, albeit in the case of the jury, a very small amount. Our primary goal as jurors was to get this thing over as quickly as possible and get the hell out of there—with justice achieved, of course.

What was clear, however, was that the facts mattered less than the various personalities of the jury. And, after much deliberation, our “open and shut case” was still wide open. In order to break the gridlock, we watched the film of the obviously drunk driver again, and again, and again. Each time as the film ended those who felt a kinship with the young man began with endless reimaginings and speculations, none of which were actually observable, but were, nonetheless, alive and well in their hearts and minds.

Eventually, a young woman, well dressed and educated, made her case, systematically, unfolding the evidence until agreement could be kept at bay no longer. The hung jury was forced to sever the hangman’s noose of empathy and imagination and do their jobs. It was, to say the least, eye opening.

There were those on the jury who would have gladly thrown the concept of evidence out the window and used an Ouija board, or possibly attempted to channel the Ghost of Christmas Past instead. It was what they felt, deep within the recesses of their hearts that mattered, not the evidence. Who could trust in steely logic, when in fact, they didn't know what logic was.

In the end, justice was done, at least I think it was, although, just barely.

It was then that I made a deep personal commitment to never be prosecuted for a crime. As a juror I became acutely aware that even if I was innocent, that my demeanor, my haircut, or possibly an ill fitting suit could be my undoing. Not that I intended to commit a crime, but, if ever I had such an impulse, my experiences on Jury duty cured me of my criminal intent.

The accused repeatedly failed every part of the sobriety test, and even admitted to the officer that he had too much to drink. A case doesn't get much more open and shut than that. And yet, with his guilt a mere afterthought, he showed up for his trial with an attorney who pleaded his actions as a forgivable slight. After all, hasn't everyone, at one time or the other, pushed the boundaries of the law in equally small ways, but not gotten caught? What harm was done? Clearly he was sorry—and he wasn't really all that drunk anyway. Maybe the cop was a tad overzealous, a well-meaning but overeager legalist with an itchy ticket finger.

As the presentation portion of the trial came to an end, we were sent off to uphold our part of the bargain and do justice, to find the cold, hard truth. But then, something happened. The words of the defending attorney began to ring deep within the recesses of the jury’s consciousness. The empathetic impulses of the men and women who had been carefully chosen on the basis of just such sympathies began to have second thoughts—it was at this point, that the justifications began to flow like a river. The “maybes” and the “what ifs” took precedence over the facts, and with their own distant sense of guilt acting as a catalyst, some on the jury began to reinterpret the evidence.

Choosing a jury is a game of oneupmanship. The defense attempts to stack the deck of personality types in their favor and the prosecution does likewise, with justice as the remote, but ultimate goal. Inevitably, if the attorneys are more or less equally clever, there will be an uneasy compromise. With neither side having an unfair advantage, it could be seen as a case of mutual competence, or incompetence in some cases, making for a level playing field.

Both sides choose based on demographics. Race, sex, class, education, political affiliation are all factored when picking a "discriminating" juror--with all other tactical advantages being utilized judiciously. We potential jurors were sized up and down, with questions stated, but carefully phrased in a coded appeal to our sympathies, a verbal Rorschach Test intended to separate the wheat from the chaff.

In reality, legal trials aren't a search for the truth as much as a game played for money, no different than any other game, like baseball, or politics. Justice is the goal, at least abstractly, and everyone gets paid; judge, attorneys and even the jury, albeit in the case of the jury, a very small amount. Our primary goal as jurors was to get this thing over as quickly as possible and get the hell out of there—with justice achieved, of course.

What was clear, however, was that the facts mattered less than the various personalities of the jury. And, after much deliberation, our “open and shut case” was still wide open. In order to break the gridlock, we watched the film of the obviously drunk driver again, and again, and again. Each time as the film ended those who felt a kinship with the young man began with endless reimaginings and speculations, none of which were actually observable, but were, nonetheless, alive and well in their hearts and minds.

Eventually, a young woman, well dressed and educated, made her case, systematically, unfolding the evidence until agreement could be kept at bay no longer. The hung jury was forced to sever the hangman’s noose of empathy and imagination and do their jobs. It was, to say the least, eye opening.

There were those on the jury who would have gladly thrown the concept of evidence out the window and used an Ouija board, or possibly attempted to channel the Ghost of Christmas Past instead. It was what they felt, deep within the recesses of their hearts that mattered, not the evidence. Who could trust in steely logic, when in fact, they didn't know what logic was.

In the end, justice was done, at least I think it was, although, just barely.

It was then that I made a deep personal commitment to never be prosecuted for a crime. As a juror I became acutely aware that even if I was innocent, that my demeanor, my haircut, or possibly an ill fitting suit could be my undoing. Not that I intended to commit a crime, but, if ever I had such an impulse, my experiences on Jury duty cured me of my criminal intent.

Jury duty is only one of the ways in which the ability to sift evidence with some degree of conscious objectivity is frequently abandoned in favor of more arcane methods of “Knowing.” Religion, and even science, frequently place self-interest and profit above a genuine hunt for the truth. This is, apparently, a uniquely human trait, at least when it comes to the kinds of ponderous half-truths and partial lies that are the byproduct of a correspondingly sized brain.

Most recently the Benghazi attacks that ended in the deaths of a U.S. Ambassador and three other American military personal is a fine example of selective objectivity. The type of which is too typical of the media and their political cronies. As the evidence mounts that the Obama Administration lied, including former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, people begin to take sides, rallying the wagons in an effort to protect "bigger ideas." If justice must be sacrificed for a time, then so be it.

Inevitably, the objections and arguments are reduced to a more fitting size, usually stated as something like, "So what if they're guilty, Bush wasn't any better"! This gives new meaning to the old phrase "an eye for an eye." These are simple, manageable, justifications, ones that are pocket sized, easy to carry, and readily available when necessary. When speaking to fellow travelers, nothing more is needed.

At this point, personal dogma, like racial solidarity at a lynching, begins to lose its amorphous shape and become more tangible. The Ku Klux Klan, The Nation of Islam, old school Republican and Democratic ideologues, sit side by side with radical feminists, corporate leeches, socialists and billionaires, divvying up the spoils won in the war against the citizenry. All while the citizens actively engage in their own suicide, voting again and again for the same thugs and punks in both parties.

A good speech, whether by a politician, or an attorney, spoken in code to a sympathetic jury, always serves the same purpose—to mislead with a sleight of hand, using well-worn tricks offered by silver tongued devils and angels alike.

It is this ability, or, more accurately, this inability, to rationally weigh the facts that is at the heart of it all. And, as long as we are happy to be “Happy,” with eyes fixed permanently on those things that matter least, it’s unlikely that it will ever be otherwise.

Mark Magula

Most recently the Benghazi attacks that ended in the deaths of a U.S. Ambassador and three other American military personal is a fine example of selective objectivity. The type of which is too typical of the media and their political cronies. As the evidence mounts that the Obama Administration lied, including former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, people begin to take sides, rallying the wagons in an effort to protect "bigger ideas." If justice must be sacrificed for a time, then so be it.

Inevitably, the objections and arguments are reduced to a more fitting size, usually stated as something like, "So what if they're guilty, Bush wasn't any better"! This gives new meaning to the old phrase "an eye for an eye." These are simple, manageable, justifications, ones that are pocket sized, easy to carry, and readily available when necessary. When speaking to fellow travelers, nothing more is needed.

At this point, personal dogma, like racial solidarity at a lynching, begins to lose its amorphous shape and become more tangible. The Ku Klux Klan, The Nation of Islam, old school Republican and Democratic ideologues, sit side by side with radical feminists, corporate leeches, socialists and billionaires, divvying up the spoils won in the war against the citizenry. All while the citizens actively engage in their own suicide, voting again and again for the same thugs and punks in both parties.

A good speech, whether by a politician, or an attorney, spoken in code to a sympathetic jury, always serves the same purpose—to mislead with a sleight of hand, using well-worn tricks offered by silver tongued devils and angels alike.

It is this ability, or, more accurately, this inability, to rationally weigh the facts that is at the heart of it all. And, as long as we are happy to be “Happy,” with eyes fixed permanently on those things that matter least, it’s unlikely that it will ever be otherwise.

Mark Magula

|

|

|