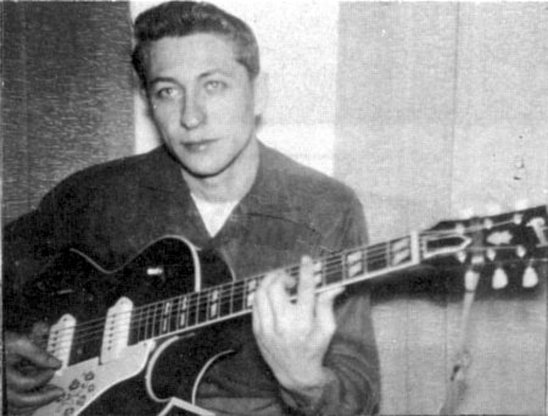

Goodbye Scotty Moore

There were two, and only two essential schools of early rock and roll guitar. One came from the singularly brilliant Chuck Berry. And the other came from Scotty Moore. Others would follow, but most emerged out of one or the other, maybe some combination of the two. Scotty got their first, about a year before Chuck recorded. Scotty in 1954 with a very young Elvis Presley at Sun records, before Sun, was anything more than a gleam in Sam Phillip’s eye. Chuck began his career at the equally legendary Chess records in 1955.

In a very real sense, both Scotty and Chuck were country musicians with strong blues roots. Ike Turner, the man who got there before any of them with the Jackie Brenston hit “Rocket 88” way back in 1951, saw Berry as a countrified Black man who sounded White. Just listen to Berry’s first release, Maybelline, and you’ll see why. Similarly, Scotty Moore was a White kid playing the blues ala BB King, with a heavy dose of Merle Travis and Chet Atkins to leaven the mix. This wasn’t a completely new phenomenon, but it was rare enough, especially in recorded music, since such cross-pollination was hard to market. Who do you market it too? The White Honky-Tonk music fan or the predominately Black R&B market.

The musicians, however, didn’t really care, they just played what they heard on the radio, on television, and in their communities. Even segregated cities in the Deep South with seperate Black and White sections of town, people lived and worked in close enough proximity to experience one another’s music, which was never any more than an earshot away. The music had yet to break-out beyond the South to any real degree, even though jazz had tenuously made the trek decades before.

Pop culture, for the most part, remained racially isolated, for fear of offense to advertisers. Not even the hugely popular Nat Cole could bridge that gap, as his short-lived TV series in the 1950’s exemplified.

It was a young, almost effeminately pretty Southern boy, Elvis Presley that eventually did bridge the gap. Whether he ever would have without Scotty Moore, is in serious doubt.

Scotty Mentored the young Elvis, under the watchful eye of rock and roll’s great seer, Sam Phillips, a man with dollar signs in his eyes, but a genuine abiding love for Black music, which gave Elvis a safe place to incubate his sound. That’s how Elvis went from the kid who just wanted to make a record for his mamma, to the first, real rock and roll star. And, it was Scotty Moore that played a pivotal role as prime musical accompanist, big brother and road manager.

Just how good a guitarist was Scotty Moore, really? He was already a pro in 1954, with big ears and a genuine feel for this hybrid form of music that was about to start a revolution. His playing is heavily Merle Travis oriented, especially on the Sun sessions, which was rock and roll’s first template. But, even after Elvis went to RCA in 1956 as a solo artist, Scotty’s guitar was uniquely tough and unpredictable. I can still remember being maybe four years old and listening intently to Elvis’s early hit “Too Much,” where Scotty played a central role. This isn’t Rock-a-Billy, it isn’t even really blues. The guitars trebly sound is hard-edged and muscular as it traces the bass-line, making the whole record explode. When Scotty takes his solo, it sounds like nothing else in recorded music. It is both immediately hummable and a radical departure. Even at four, I could sing that solo. I still can more than a half a century later. That is the stuff that drives legends and sends young kids to the woodshed like Keith Richards, Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck, including just about every other guitar star of the early rock and roll era.

Even without Scotty, rock and roll was inevitable, just as it would have been absent Elvis. But it would, no doubt, have been very different. That’s why anyone with an inkling of interest in early rock music, particularly Rock-a-Billy, owes Scotty, just like they owe Elvis and Chuck Berry, Fats Domino and Little Richard.

If you happen to be a guitar player, playing within the idiom, though, you owe a debt that can scarcely be repaid. In that way, every record with a rock and roll beat needs to hand over royalties to the music’s first, and among the most influential guitarist to ever play the instrument. That’s how good, and how important, Scotty Moore was.

Mark Magula

In a very real sense, both Scotty and Chuck were country musicians with strong blues roots. Ike Turner, the man who got there before any of them with the Jackie Brenston hit “Rocket 88” way back in 1951, saw Berry as a countrified Black man who sounded White. Just listen to Berry’s first release, Maybelline, and you’ll see why. Similarly, Scotty Moore was a White kid playing the blues ala BB King, with a heavy dose of Merle Travis and Chet Atkins to leaven the mix. This wasn’t a completely new phenomenon, but it was rare enough, especially in recorded music, since such cross-pollination was hard to market. Who do you market it too? The White Honky-Tonk music fan or the predominately Black R&B market.

The musicians, however, didn’t really care, they just played what they heard on the radio, on television, and in their communities. Even segregated cities in the Deep South with seperate Black and White sections of town, people lived and worked in close enough proximity to experience one another’s music, which was never any more than an earshot away. The music had yet to break-out beyond the South to any real degree, even though jazz had tenuously made the trek decades before.

Pop culture, for the most part, remained racially isolated, for fear of offense to advertisers. Not even the hugely popular Nat Cole could bridge that gap, as his short-lived TV series in the 1950’s exemplified.

It was a young, almost effeminately pretty Southern boy, Elvis Presley that eventually did bridge the gap. Whether he ever would have without Scotty Moore, is in serious doubt.

Scotty Mentored the young Elvis, under the watchful eye of rock and roll’s great seer, Sam Phillips, a man with dollar signs in his eyes, but a genuine abiding love for Black music, which gave Elvis a safe place to incubate his sound. That’s how Elvis went from the kid who just wanted to make a record for his mamma, to the first, real rock and roll star. And, it was Scotty Moore that played a pivotal role as prime musical accompanist, big brother and road manager.

Just how good a guitarist was Scotty Moore, really? He was already a pro in 1954, with big ears and a genuine feel for this hybrid form of music that was about to start a revolution. His playing is heavily Merle Travis oriented, especially on the Sun sessions, which was rock and roll’s first template. But, even after Elvis went to RCA in 1956 as a solo artist, Scotty’s guitar was uniquely tough and unpredictable. I can still remember being maybe four years old and listening intently to Elvis’s early hit “Too Much,” where Scotty played a central role. This isn’t Rock-a-Billy, it isn’t even really blues. The guitars trebly sound is hard-edged and muscular as it traces the bass-line, making the whole record explode. When Scotty takes his solo, it sounds like nothing else in recorded music. It is both immediately hummable and a radical departure. Even at four, I could sing that solo. I still can more than a half a century later. That is the stuff that drives legends and sends young kids to the woodshed like Keith Richards, Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck, including just about every other guitar star of the early rock and roll era.

Even without Scotty, rock and roll was inevitable, just as it would have been absent Elvis. But it would, no doubt, have been very different. That’s why anyone with an inkling of interest in early rock music, particularly Rock-a-Billy, owes Scotty, just like they owe Elvis and Chuck Berry, Fats Domino and Little Richard.

If you happen to be a guitar player, playing within the idiom, though, you owe a debt that can scarcely be repaid. In that way, every record with a rock and roll beat needs to hand over royalties to the music’s first, and among the most influential guitarist to ever play the instrument. That’s how good, and how important, Scotty Moore was.

Mark Magula