Robert & Jimi and the 27 Blues

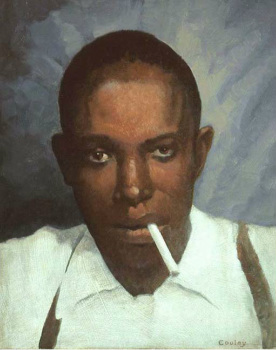

Long before anybody knew anything much about Robert Johnson, there was the legend. How much was true didn't matter, it was the extraordinary back-story for what was the most gifted blues musician that folk-blues has ever produced. The legend was great P.R. for a cipher, a blank slate—and a way in which to imagine Johnson as whatever you wanted him to be. The music should have been enough, but it almost never is. In just about every art-form, the artist must have a story that draws their audience in, a way to sell more than paint on canvas or a marketable face and figure. In Robert Johnson’s case, it was the Devil.

He was the first heavy metal musician, a virtuoso in a primitive medium, with a gift for mimicry, an abundance of technique and a poet’s instinct for lyrical imagery. That he often borrowed the raw materials for his songs from the older musicians that recorded before him—Skip James, Son House, Blind Willie McTell or Lonnie Johnson made it clear that he knew what good was. Everyone steals, but very few know what to do with the goods once they've taken possession.

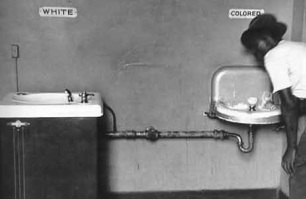

He was a child of poverty, Jim Crow and the emerging technology of the portable phonograph and the juke box. That, and substantial-innate gifts, were enough to make him one of what Jaco Pastorius, another self-taught genius used to call, the “Cats.” Hank Williams, Charlie Parker, Beethoven, John Coltrane were among the few to make the list.

He was the first heavy metal musician, a virtuoso in a primitive medium, with a gift for mimicry, an abundance of technique and a poet’s instinct for lyrical imagery. That he often borrowed the raw materials for his songs from the older musicians that recorded before him—Skip James, Son House, Blind Willie McTell or Lonnie Johnson made it clear that he knew what good was. Everyone steals, but very few know what to do with the goods once they've taken possession.

He was a child of poverty, Jim Crow and the emerging technology of the portable phonograph and the juke box. That, and substantial-innate gifts, were enough to make him one of what Jaco Pastorius, another self-taught genius used to call, the “Cats.” Hank Williams, Charlie Parker, Beethoven, John Coltrane were among the few to make the list.

Johnson wasn’t the first blues musician to use the devil as a lyrical device or as a way of creating a menacing aura. Peetie Wheetstraw, known as “the devil’s son-in-law” had done it, so had a few others—but in Robert Johnson’s case, it was believable.

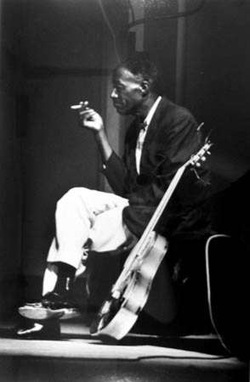

Son House was one of the best and earliest country bluesmen to make records and knew Johnson as a boy. House and his guitar partner, Willie Brown, used to run into a young Robert at local parties, where Johnson would beg for the opportunity to play when the older musicians would take a break between sets. “Robert would try and play the guitar at country picnics and make the most god-awful noise,” House would say, “people began to boo, and poor Robert had to high-tail it outta there.” Whatever promise Johnson may have had as a musician wasn’t evident at that stage of his life.

Son and Willie left the area, traveling throughout the delta, playing at country get-togethers and occasionally making records. A year or so later they returned to the vicinity and were playing a party when Robert asked to try his hand again—only to be told to get lost. Son must have thought that he was saving the young man from more embarrassment. Eventually, House and Brown relented and gave the kid his shot—this time things were different. Robert began to play chord patterns that were adapted from the great, two fisted boogie piano players of the period like Pete Johnson; only he was playing them with one hand on a guitar with six strings, not two hands and eighty-eight keys. He punctuated his singing with chord fills, and a slide technique that was so good it made Son House and the other delta masters sound crude by comparison.

No one could get that good that quick, not when he had been so bad only a year before. When Johnson finished, House asked him how it was possible, Johnson said he went down to the crossroads and sold his soul to an old man named Legba—the devil—and the legend was born. It was Johnson’s astonishing skill that gave weight to the supernatural claim—and it made one hell of a story.

Son House was one of the best and earliest country bluesmen to make records and knew Johnson as a boy. House and his guitar partner, Willie Brown, used to run into a young Robert at local parties, where Johnson would beg for the opportunity to play when the older musicians would take a break between sets. “Robert would try and play the guitar at country picnics and make the most god-awful noise,” House would say, “people began to boo, and poor Robert had to high-tail it outta there.” Whatever promise Johnson may have had as a musician wasn’t evident at that stage of his life.

Son and Willie left the area, traveling throughout the delta, playing at country get-togethers and occasionally making records. A year or so later they returned to the vicinity and were playing a party when Robert asked to try his hand again—only to be told to get lost. Son must have thought that he was saving the young man from more embarrassment. Eventually, House and Brown relented and gave the kid his shot—this time things were different. Robert began to play chord patterns that were adapted from the great, two fisted boogie piano players of the period like Pete Johnson; only he was playing them with one hand on a guitar with six strings, not two hands and eighty-eight keys. He punctuated his singing with chord fills, and a slide technique that was so good it made Son House and the other delta masters sound crude by comparison.

No one could get that good that quick, not when he had been so bad only a year before. When Johnson finished, House asked him how it was possible, Johnson said he went down to the crossroads and sold his soul to an old man named Legba—the devil—and the legend was born. It was Johnson’s astonishing skill that gave weight to the supernatural claim—and it made one hell of a story.

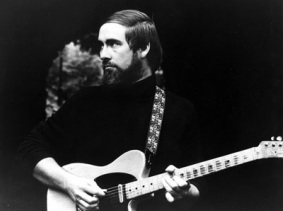

Remarkably, the legend was carried through the generations and re-told and co-opted by musicians looking to build their own myth. A young Robbie Robertson at the beginning of his career heard similar stories from the slightly older guitar-master Roy Buchanan—and again, it was the substance of Buchanan’s gift that made it believable—at least to an aspiring young player looking to find a way get a head up.

In 1969, a band of young Englishmen took the powerful iconography of Satan to a new audience and solidified the growing movement in “Heavy music,” creating the template for “Heavy Metal.” Black Sabbath used the same basic devices of thick, two-note chords, drop tunings, displays of guitar bravado and demonically-themed lyrics as an image and hook to sell their music. None of this was surprising, since their influences had been bands like Cream, The Jimi Hendrix Experience and Led Zeppelin, all of which were heavily influenced by Robert Johnson’s music.

Eric Clapton has long championed Johnson, claiming him as a primary influence. His elevation to god-status in the early days of his career and his struggle with addiction found a parallel in Johnson’s own struggles with women and drink—the difference being the brevity of Roberts’s life.

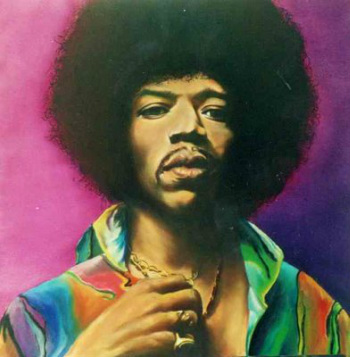

A better comparison would be Jimi Hendrix. Both died at twenty seven, both took a very diverse range of pre-existing musical traditions and completely reimagined them. Both, also had the experience early in their careers of being rejected and booed off the stage—and within relatively short periods of time re-emerged as among the finest players in the world. Lots of people get booed; but very few ever go on to be the best of the best.

Jimi Hendrix was born a generation after Robert Johnson. He was from Seattle, a northern urban paradise compared to the Mississippi of the 1930’s that was the back-drop for poor southern blacks like Johnson. He grew up in a black middle class family, graduated high school, and then became a paratrooper in the U.S. military. He, like Johnson, listened intently to records and the radio, moving from deep blues to free-jazz, soul music and rock and roll, absorbing all of it. Hendrix spent his pre-fame years touring the chitlin' circuit in black nightclubs with the Isley Brothers, Little Richard and playing in organ trios with Curtis Knight. Like Johnson, he developed a way of playing that could mimic a whole band or a horn section with chords and fills, taking the blues style of B.B. King, Albert King and Buddy Guy as the basis for his solos.

In 1969, a band of young Englishmen took the powerful iconography of Satan to a new audience and solidified the growing movement in “Heavy music,” creating the template for “Heavy Metal.” Black Sabbath used the same basic devices of thick, two-note chords, drop tunings, displays of guitar bravado and demonically-themed lyrics as an image and hook to sell their music. None of this was surprising, since their influences had been bands like Cream, The Jimi Hendrix Experience and Led Zeppelin, all of which were heavily influenced by Robert Johnson’s music.

Eric Clapton has long championed Johnson, claiming him as a primary influence. His elevation to god-status in the early days of his career and his struggle with addiction found a parallel in Johnson’s own struggles with women and drink—the difference being the brevity of Roberts’s life.

A better comparison would be Jimi Hendrix. Both died at twenty seven, both took a very diverse range of pre-existing musical traditions and completely reimagined them. Both, also had the experience early in their careers of being rejected and booed off the stage—and within relatively short periods of time re-emerged as among the finest players in the world. Lots of people get booed; but very few ever go on to be the best of the best.

Jimi Hendrix was born a generation after Robert Johnson. He was from Seattle, a northern urban paradise compared to the Mississippi of the 1930’s that was the back-drop for poor southern blacks like Johnson. He grew up in a black middle class family, graduated high school, and then became a paratrooper in the U.S. military. He, like Johnson, listened intently to records and the radio, moving from deep blues to free-jazz, soul music and rock and roll, absorbing all of it. Hendrix spent his pre-fame years touring the chitlin' circuit in black nightclubs with the Isley Brothers, Little Richard and playing in organ trios with Curtis Knight. Like Johnson, he developed a way of playing that could mimic a whole band or a horn section with chords and fills, taking the blues style of B.B. King, Albert King and Buddy Guy as the basis for his solos.

In 1967, when Hendrix exploded onto the scene, segregation was still rigidly enforced in the south; the civil rights movement had begun the process of change with the Supreme Court decision Brown v. the Board of education in 1954. Other landmark cases in 1963/64 opened doors for African Americans, but social change was slow in coming. Neighborhoods were segregated, as were most businesses and schools. The legal system had changed, but the artificial line in the sand was, in most cases, still intact. This was less true in the north, but still prevalent in most cities. However, in relation to the culture that Robert Johnson was born into, there was a world of difference. Johnson hopped freight trains, alone and with various traveling partners like Robert-Junior Lockwood, his unofficially-adopted son from a liaison with a woman on one of his many road trips, and sometimes with Johnny Shines. Both Lockwood and Shines were only a few years younger than Johnson and accomplished players in their own right, but lived in his shadow, learning from him, watching his genius up close and personal. Lockwood would go on to become one of the blues' preeminent session players, performing on countless records behind Little Walter among others, fashioning the Chicago blues sound out of the lessons learned by Johnson and his own abundant creativity. Johnny Shines was among the finest post-war country blues singers and guitarists and became a primary source of knowledge, along with Lockwood, regarding Robert’s life and music.

Robert Johnson had one big advantage over the older musicians that he learned from, most of whom had to glean what they could from whatever players might be living in, or traveling through, their vicinity. Robert came along at a time when jukeboxes and phonographs made it possible to hear a much broader range of styles, from the variety of approaches that grew up as the result of the isolated culture of the delta—odd tunings and bottleneck slide guitar—to the piedmont-finger-picked styles of Blind Blake and the virtuoso jazz-blues approach of Lonnie Johnson—or the haunting falsetto and distinct minor tunings of another idiosyncratic delta master, Skip James. Most of these musical idioms were regional in nature, making it difficult to learn without substantial traveling. In the midst of the great depression, car travel was a luxury most Southern blacks couldn’t afford (this extended to trains and buses as well). Juke boxes and radio spread the sounds of the latest artists, and cheap portable record players gave younger players like Johnson the ability to sit and play records, isolating particular licks over and over until they were absorbed into an ever expanding repertoire.

For Hendrix, the unintended consequence of racial segregation gave him a front row seat to the latest records and sounds coming out of the black community—and kept most of his white contemporary’s on the outside of the culture and music that was pouring out of black neighborhoods. His work with various black artists gave a depth and range to his playing that was inaccessible to post-Beatles Brits like Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck, both culturally and geographically.

Robert Johnson had one big advantage over the older musicians that he learned from, most of whom had to glean what they could from whatever players might be living in, or traveling through, their vicinity. Robert came along at a time when jukeboxes and phonographs made it possible to hear a much broader range of styles, from the variety of approaches that grew up as the result of the isolated culture of the delta—odd tunings and bottleneck slide guitar—to the piedmont-finger-picked styles of Blind Blake and the virtuoso jazz-blues approach of Lonnie Johnson—or the haunting falsetto and distinct minor tunings of another idiosyncratic delta master, Skip James. Most of these musical idioms were regional in nature, making it difficult to learn without substantial traveling. In the midst of the great depression, car travel was a luxury most Southern blacks couldn’t afford (this extended to trains and buses as well). Juke boxes and radio spread the sounds of the latest artists, and cheap portable record players gave younger players like Johnson the ability to sit and play records, isolating particular licks over and over until they were absorbed into an ever expanding repertoire.

For Hendrix, the unintended consequence of racial segregation gave him a front row seat to the latest records and sounds coming out of the black community—and kept most of his white contemporary’s on the outside of the culture and music that was pouring out of black neighborhoods. His work with various black artists gave a depth and range to his playing that was inaccessible to post-Beatles Brits like Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck, both culturally and geographically.

Hendrix absorbed the elegant rhythm artistry of Curtis Mayfield, the steely single-note playing of Buddy Guy and B.B. King, the use of octaves from Wes Montgomery, the country blues of Muddy Waters and Lightning Hopkins and, from the most divergent of sources, the song-craft, poetic gifts and vocal styling’s of Bob Dylan as well as the studio artistry of the Beatles. He was a walking amalgam of black and white, contemporary and traditional approaches from across a uniquely wide spectrum—taken together with a need to play, and a voluminous appetite for the extreme and the exotic; he became the greatest electric guitarist of his time—and probably of the last sixty years.

Just as Johnson had a generation before, Hendrix distilled these various elements into what was, up until his time, disparate forms isolated by race, culture and geography—and turned them into an extraordinary guitar technique with an equally wide-ranging compositional style. Both Robert and Jimi were regarded by their contemporaries as untouchable in terms of their talents, even by their most gifted peers.

Some twenty years after Jimi’s death I had a chance to play with a very good bass player in a strangely eclectic band that was part gospel, jazz, rock and R&B. His wife was an attractive woman with long blonde hair and Scandinavian features, and just happened to be one of Jimi’s last girlfriends before his untimely demise. Our band would travel around playing random gigs wherever people would have us—and somehow it never dawned on me, until many years later, that she was listening to me play guitar on a nightly basis—and that those same ears and eyes probably sat in front of a young Hendrix, listening to him play his latest compositions on acoustic guitar, jamming at clubs, and from backstage at some of Jimi’s biggest gigs—and with some of the finest players of the era. I should have been awed, but like younger men tend to be, I was caught up in my own thing—too oblivious to ask questions. Maybe it seemed impolite to talk about her former-lover in front of her brand-new husband. I hope that was my reason, although I don’t really remember!

Just as Johnson had a generation before, Hendrix distilled these various elements into what was, up until his time, disparate forms isolated by race, culture and geography—and turned them into an extraordinary guitar technique with an equally wide-ranging compositional style. Both Robert and Jimi were regarded by their contemporaries as untouchable in terms of their talents, even by their most gifted peers.

Some twenty years after Jimi’s death I had a chance to play with a very good bass player in a strangely eclectic band that was part gospel, jazz, rock and R&B. His wife was an attractive woman with long blonde hair and Scandinavian features, and just happened to be one of Jimi’s last girlfriends before his untimely demise. Our band would travel around playing random gigs wherever people would have us—and somehow it never dawned on me, until many years later, that she was listening to me play guitar on a nightly basis—and that those same ears and eyes probably sat in front of a young Hendrix, listening to him play his latest compositions on acoustic guitar, jamming at clubs, and from backstage at some of Jimi’s biggest gigs—and with some of the finest players of the era. I should have been awed, but like younger men tend to be, I was caught up in my own thing—too oblivious to ask questions. Maybe it seemed impolite to talk about her former-lover in front of her brand-new husband. I hope that was my reason, although I don’t really remember!

Both Jimi and Robert lived in similar ways and died in similar ways; Robert was poisoned by the jealous husband of a lover and Jimi by a drug overdose. Robert spent his final hours in agony, on his knees vomiting, barking like a dog, lingering until the Hellhound of his most famous song could be kept at bay no longer. Jimi died in a lover’s bed choking on his own vomit.

There’s more than one way to sell your soul; you don’t have to stand at the crossroads at midnight, waiting for the old man named Legba to show up. You can sign a contract that steals it a bit at a time, like Jimi did—or by tempting fate in the bed of a married woman. What lasts, however, is the music, although it might be nice to enjoy it beyond a meager twenty-seven years. As any economist will tell you, there is a price to be paid for everything.

Greatness is an adjective that has come to be so overused used in our culture that it has effectively been rendered meaningless. A well-known jazz writer was asked, after winning the genius grant for his work, whether he considered the award to be appropriate. He responded; “if Madonna’s a genius, then I’m definitely a genius. But, if Duke Ellington is the standard of genius, then I would have to say no.”

Everyone needs a standard, a way of measuring the best of the best, a goal to aspire to. So many of today’s musicians are hailed as the latest in a never ending line of geniuses, marketed for a few hot licks and a compelling grimace when hitting the high notes. For millions of others, including myself, Robert and Jimi remain the standard, as guitar players and songwriters—and for their endless creativity. And very few, maybe none, will ever quite meet their measure.

Mark Magula

There’s more than one way to sell your soul; you don’t have to stand at the crossroads at midnight, waiting for the old man named Legba to show up. You can sign a contract that steals it a bit at a time, like Jimi did—or by tempting fate in the bed of a married woman. What lasts, however, is the music, although it might be nice to enjoy it beyond a meager twenty-seven years. As any economist will tell you, there is a price to be paid for everything.

Greatness is an adjective that has come to be so overused used in our culture that it has effectively been rendered meaningless. A well-known jazz writer was asked, after winning the genius grant for his work, whether he considered the award to be appropriate. He responded; “if Madonna’s a genius, then I’m definitely a genius. But, if Duke Ellington is the standard of genius, then I would have to say no.”

Everyone needs a standard, a way of measuring the best of the best, a goal to aspire to. So many of today’s musicians are hailed as the latest in a never ending line of geniuses, marketed for a few hot licks and a compelling grimace when hitting the high notes. For millions of others, including myself, Robert and Jimi remain the standard, as guitar players and songwriters—and for their endless creativity. And very few, maybe none, will ever quite meet their measure.

Mark Magula

|

|

|