Hearing Junior Wells “On Tap'' one more Time

Hearing Junior Wells “On Tap,'' one more time

It was the 1970s. I’m not sure what that means, even though I can still see it, hear it, taste it, almost touch it, but not quite. I was there, so memory provides a movie in my head, with the appropriate scenery, clothes, and cars. Music sounded like what it was, a bit of the 1950’s, lots of the 1960’s, with the newest recording and playback technology, 1970’s style. Looking back, it sounds like my life, and that’s enough to make me listen, like someone who was there. Because I was.

I find that some, maybe most of us, eventually, gravitate back to our parent's generation, their music, their cars, sometimes, even our grandparents, when I want to hear older jazz or blues, which I do, often enough. For me, Ray Charles sounds like home. Sinatra sounds like a great big movie, on a big screen, with a trip downtown on a Saturday night. Stopping at the soda shop for a milkshake, walking main-street between the stores, block after block of stores.

A hot dog was a quarter. A hamburger 30cents. Cheese, an extra nickel. Comic books were 12 cents. You could buy six candy bars for a quarter. A bottle of pop was 10 cents. A bag of chips, a dime. All of these things are what time feels like. What music sounds like, as it makes its way thru my ears, to my head, and then my heart.

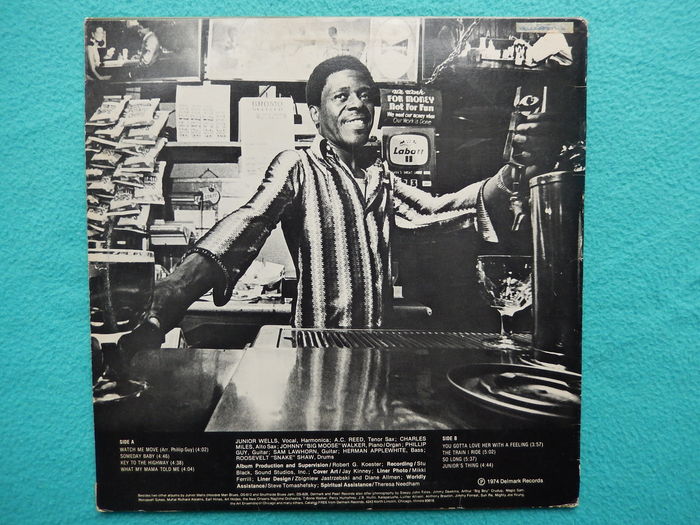

We all hear the music differently, everyone does, and for very personal reasons. Today, for instance, I heard Junior Wells; “On Tap,” a stunningly good blues record, loaded with sixties soul and fifties blues, part James Brown, part Sonny Boy Williamson, either Rice Miller or John Lee Williamson, take your pick. By 1976, when the album was released, fifties blues and sixties soul were passe’. Disco had taken over, and rock & roll was money. Big money. Meaning, no one wanted to hear that passe’ music, that old, slavery-type music, except the diehards, the true believers. For me, though, the music was like fresh air being pumped into a collapsed coal mine.

Part of what made it so special was you couldn’t hear this kind of authentic blues, anywhere The radio didn’t play it. Television wasn’t interested. Most of the records were out of print, and probably never sold more than a few thousand copies, anyway. So, you had to scour the underground records stores and flea markets, instead of the 5 & 10’s, which is where you’d normally go to find a new record. Proving once again, that if we desire something badly enough—and it’s in short supply—it becomes like gold.

That’s how I first heard Junior Wells record “On Tap,” like it was gold.

This was not a rock & roll band. There were no massive banks of amplifiers. No duel bass drums straddled like a giant octopus across the stage. Junior’s band was stripped down, at least by modern standards, making the band more supple. More grooving. Sammy Lawhorn played his Gibson 335 with a blues induced savoir-faire, soulfully elegant and down-home funky, a tough mixture to achieve, for sure.

On the other guitar, was Phil Guy, the legendary Buddy Guy’s younger brother, who played with his own bluesy sophistication and rhythmic intensity. Like Buddy, but with a tad more polish, as one might expect from a younger sibling. The two, Phil with his strat, and Sammy’s with his 335 made a fine blues, guitar team. Very different from one another, but still complimentary.

Junior's music was stone blues, soul-blues, dance and funk blues, telling stories, kind-of blues. This was not, stand on the stage, face grimacing, while the big light show signals it’s time for your blazing licks, which will be sent to the audience like a shock-wave, kind-of blues. Which is what most young, White teens had grown up hearing. That other thing, that was what made Junior Wells sound like a fresh and funky wind, caressing your ears. It was different but familiar. It was like a home away from home.

The band’s version of Junior Parker’s Mystery Train, with its late funk, early disco meets Sonny Boy Williamson by the way of James Brown groove, is a really fine example of the kind of music played in Black clubs, by Black bands, for Black patrons. This gave the music an air of the exotic, not just for White folk, but younger Blacks too, who hadn’t grown up hanging around a South Side Chicago club, in the heart of a segregated inner city. Junior’s band, on another James Brown-influenced song “Watch Me Move,” digs deep into the syncopated groove, moving like a fine-tuned, pimped-out caddy. There is no lengthy drum solo. Or bass solo. Just a tight band of seasoned musicians, doing what they’d been doing as veteran performers for a quarter century.

Here’s the thing, back then, there were only a small handful of places on earth you could hear that kind music, being played live, by the people who created it. That’s how rare it was, and it’s why it seemed like a diamond. Because it was. Rare like a diamond, not ubiquitous, like the endless pop-culture machine that churns out product with an assembly-line efficiency. There were echoes of another world in Junior's music. Or, some far away place, just down the street, and most-likely, off limits. In other words, Junior Wells “On Tap” wasn’t just music. Real music never is. Memory, experience, expectation—all of these things inform the way we hear the music—and that’s what makes it special, and personal, as well as a lasting part of who we are.

Mark Magula

It was the 1970s. I’m not sure what that means, even though I can still see it, hear it, taste it, almost touch it, but not quite. I was there, so memory provides a movie in my head, with the appropriate scenery, clothes, and cars. Music sounded like what it was, a bit of the 1950’s, lots of the 1960’s, with the newest recording and playback technology, 1970’s style. Looking back, it sounds like my life, and that’s enough to make me listen, like someone who was there. Because I was.

I find that some, maybe most of us, eventually, gravitate back to our parent's generation, their music, their cars, sometimes, even our grandparents, when I want to hear older jazz or blues, which I do, often enough. For me, Ray Charles sounds like home. Sinatra sounds like a great big movie, on a big screen, with a trip downtown on a Saturday night. Stopping at the soda shop for a milkshake, walking main-street between the stores, block after block of stores.

A hot dog was a quarter. A hamburger 30cents. Cheese, an extra nickel. Comic books were 12 cents. You could buy six candy bars for a quarter. A bottle of pop was 10 cents. A bag of chips, a dime. All of these things are what time feels like. What music sounds like, as it makes its way thru my ears, to my head, and then my heart.

We all hear the music differently, everyone does, and for very personal reasons. Today, for instance, I heard Junior Wells; “On Tap,” a stunningly good blues record, loaded with sixties soul and fifties blues, part James Brown, part Sonny Boy Williamson, either Rice Miller or John Lee Williamson, take your pick. By 1976, when the album was released, fifties blues and sixties soul were passe’. Disco had taken over, and rock & roll was money. Big money. Meaning, no one wanted to hear that passe’ music, that old, slavery-type music, except the diehards, the true believers. For me, though, the music was like fresh air being pumped into a collapsed coal mine.

Part of what made it so special was you couldn’t hear this kind of authentic blues, anywhere The radio didn’t play it. Television wasn’t interested. Most of the records were out of print, and probably never sold more than a few thousand copies, anyway. So, you had to scour the underground records stores and flea markets, instead of the 5 & 10’s, which is where you’d normally go to find a new record. Proving once again, that if we desire something badly enough—and it’s in short supply—it becomes like gold.

That’s how I first heard Junior Wells record “On Tap,” like it was gold.

This was not a rock & roll band. There were no massive banks of amplifiers. No duel bass drums straddled like a giant octopus across the stage. Junior’s band was stripped down, at least by modern standards, making the band more supple. More grooving. Sammy Lawhorn played his Gibson 335 with a blues induced savoir-faire, soulfully elegant and down-home funky, a tough mixture to achieve, for sure.

On the other guitar, was Phil Guy, the legendary Buddy Guy’s younger brother, who played with his own bluesy sophistication and rhythmic intensity. Like Buddy, but with a tad more polish, as one might expect from a younger sibling. The two, Phil with his strat, and Sammy’s with his 335 made a fine blues, guitar team. Very different from one another, but still complimentary.

Junior's music was stone blues, soul-blues, dance and funk blues, telling stories, kind-of blues. This was not, stand on the stage, face grimacing, while the big light show signals it’s time for your blazing licks, which will be sent to the audience like a shock-wave, kind-of blues. Which is what most young, White teens had grown up hearing. That other thing, that was what made Junior Wells sound like a fresh and funky wind, caressing your ears. It was different but familiar. It was like a home away from home.

The band’s version of Junior Parker’s Mystery Train, with its late funk, early disco meets Sonny Boy Williamson by the way of James Brown groove, is a really fine example of the kind of music played in Black clubs, by Black bands, for Black patrons. This gave the music an air of the exotic, not just for White folk, but younger Blacks too, who hadn’t grown up hanging around a South Side Chicago club, in the heart of a segregated inner city. Junior’s band, on another James Brown-influenced song “Watch Me Move,” digs deep into the syncopated groove, moving like a fine-tuned, pimped-out caddy. There is no lengthy drum solo. Or bass solo. Just a tight band of seasoned musicians, doing what they’d been doing as veteran performers for a quarter century.

Here’s the thing, back then, there were only a small handful of places on earth you could hear that kind music, being played live, by the people who created it. That’s how rare it was, and it’s why it seemed like a diamond. Because it was. Rare like a diamond, not ubiquitous, like the endless pop-culture machine that churns out product with an assembly-line efficiency. There were echoes of another world in Junior's music. Or, some far away place, just down the street, and most-likely, off limits. In other words, Junior Wells “On Tap” wasn’t just music. Real music never is. Memory, experience, expectation—all of these things inform the way we hear the music—and that’s what makes it special, and personal, as well as a lasting part of who we are.

Mark Magula