Lowell George and the Search for Authenticity

After years of never-ending guitar solos and even longer jams, "southern rock" limped along, riding on the backs of old Allman Brothers albums and a couple of songs by Lynard Skynard. Molly Hatchet, Grinder Switch and a few others kept the flame alive, albeit with all the furious burn of a dollar store lighter found in a swimming pool—and then came Lowell George and Little Feat. When all seemed to be lost, a band of non-Southerners led by the son of a wealthy Hollywood, California furrier managed to revitalize the form—if only for a moment.

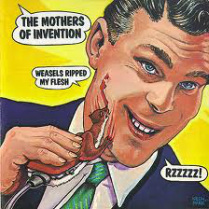

Lowell George was born with a silver spoon in his mouth—having about as much in common with the blues and country music as the movie stars that made his family wealthy. But life is funny, and often defies expected birthrights and pedigrees. What George lacked in lineage, he made up for in talent. He spent a few months as a Mother in Frank Zappa's band, one of the toughest gigs in rock—appearing on the classic "Weasels Ripped My Flesh"—probably better known for the album cover than the music. But prior to that, the closest he came to the big time was a one shot stint on the old TV show, F-Troop. He also paid some big city dues as a flautist in his high school marching band. Not a very compelling resume when contemplating southern authenticity!

Lowell George was born with a silver spoon in his mouth—having about as much in common with the blues and country music as the movie stars that made his family wealthy. But life is funny, and often defies expected birthrights and pedigrees. What George lacked in lineage, he made up for in talent. He spent a few months as a Mother in Frank Zappa's band, one of the toughest gigs in rock—appearing on the classic "Weasels Ripped My Flesh"—probably better known for the album cover than the music. But prior to that, the closest he came to the big time was a one shot stint on the old TV show, F-Troop. He also paid some big city dues as a flautist in his high school marching band. Not a very compelling resume when contemplating southern authenticity!

He met guitarist Paul Barre as a young boy, forming a friendship and musical partnership that lasted throughout his life, creating the core of what would later become Little Feat. Lowell played a variety of instruments, ultimately focusing on slide guitar—a way of playing that dated to the turn of the century and the birth of the blues—made famous by a handful of recent players, Johnny Winter, Ry Cooder and the god of Southern rock guitarists, Duane Allman. Unlike his contemporaries, he wasn't interested in the role of guitar hero. It wasn't blistering solos that drove his music; in spite of the fact that Little Feat were at least the equal of, if not superior in musicianship to most of the bands of the time. It was song craft, soulful vocals and harmonies, self-effacing humor and a very high level of play, all used in service of the music, that was Little Feat's modus operandi—and the reason why they became critical darlings.

In the video below, Lowell and Little Feat are being interviewed by a German journalist and television crew. George begins to explain his approach to slide-guitar and how he got his particular sound, and then demonstrates it by playing a few choruses of his song, China White. I've always felt that the substance of an artist can best be seen when you strip away the layers of production, remove the accompaniment, and leave them alone to perform. If you can hack that kind of isolation and shine, you may really have something to build on. George begins to play and sing in a completely unaffected style, bringing to mind Blind Willie Johnson—a very heavy pair of shoes to walk in. And then, on cue, the band begins to fill in with harmonies that invoke the best gospel tradition, finding common ground between old spirituals and prison work songs. When they finish, the only thing the interviewer can think to ask is, "Is that difficult"?

Europeans have generally approached American musical traditions in terms of what they believe they represent—civil rights, racial struggles and their general assumptions regarding the ignorance of Americans and their culture. Making it easy to feel a certain reverence for the unschooled musician as a kind of idiot savant, and yet, still feel a comfortable disdain for the larger culture they come from. This same critical attitude is prevalent in America’s predominantly white, liberal, east coast, college educated, intellectual class—and has been so throughout most of the twentieth century, continuing to the present day. Backgrounds that are often vastly different from those of the artists they write about.

An interviewer once asked Thelonious Monk what kind of music he liked. He answered, "All kinds of music"! The interviewer continued, "Even country music?" assuming that Thelonious, a symbol of all that was hip in the musical avant-garde, could never possibly answer in the affirmative. Instead, Monk answered the query with obvious irritation, "I said... all kinds of music"!

In the video below, Lowell and Little Feat are being interviewed by a German journalist and television crew. George begins to explain his approach to slide-guitar and how he got his particular sound, and then demonstrates it by playing a few choruses of his song, China White. I've always felt that the substance of an artist can best be seen when you strip away the layers of production, remove the accompaniment, and leave them alone to perform. If you can hack that kind of isolation and shine, you may really have something to build on. George begins to play and sing in a completely unaffected style, bringing to mind Blind Willie Johnson—a very heavy pair of shoes to walk in. And then, on cue, the band begins to fill in with harmonies that invoke the best gospel tradition, finding common ground between old spirituals and prison work songs. When they finish, the only thing the interviewer can think to ask is, "Is that difficult"?

Europeans have generally approached American musical traditions in terms of what they believe they represent—civil rights, racial struggles and their general assumptions regarding the ignorance of Americans and their culture. Making it easy to feel a certain reverence for the unschooled musician as a kind of idiot savant, and yet, still feel a comfortable disdain for the larger culture they come from. This same critical attitude is prevalent in America’s predominantly white, liberal, east coast, college educated, intellectual class—and has been so throughout most of the twentieth century, continuing to the present day. Backgrounds that are often vastly different from those of the artists they write about.

An interviewer once asked Thelonious Monk what kind of music he liked. He answered, "All kinds of music"! The interviewer continued, "Even country music?" assuming that Thelonious, a symbol of all that was hip in the musical avant-garde, could never possibly answer in the affirmative. Instead, Monk answered the query with obvious irritation, "I said... all kinds of music"!

Charlie Parker was said to be a big Tex Ritter fan and Sonny Rollins, the" Tenor Colossus," recorded one of his most highly acclaimed records "Way out West" as a tribute to the "white" cowboy movie heroes of his youth. Ruth Brown, the Queen of Rhythm and Blues and the mother of rock and roll, began singing with the desire to be like her idol Doris Day.

The great trumpet player, bandleader and musical innovator, Dizzy Gillespie, was asked in an interview,"Do you believe that white people can play authentic Jazz"? Dizzy, being a philosopher by nature, answered, "To say that only blacks can play jazz, is to maybe say, that’s all they can play—and black people can do whatever they want"! He understood the circular nature of the question, and by personalizing it, made it clear that what the journalist intended as a compliment, was nothing of the kind.

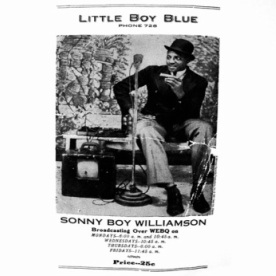

Rice Miller, better known as "Sonny Boy Williamson no. 2" co-opted the pseudonym from the original Sonny Boy Williamson, a contemporary whose real name was John Lee Williamson, exploiting it for a buck, claiming to be the original. Decades after both were gone, Miller’s ruse was forgiven and even laughed about. It was clear that, no matter what the alias, he was one of the finest singer/harmonica players and songwriters the blues ever produced. But then Sonny Boy no.2 had what Muhammad Ali used to call, "the right complexion and the right connection," sufficient to satisfy the critic's preconceptions regarding the authentic “Black” and "Blues" experience.

The great trumpet player, bandleader and musical innovator, Dizzy Gillespie, was asked in an interview,"Do you believe that white people can play authentic Jazz"? Dizzy, being a philosopher by nature, answered, "To say that only blacks can play jazz, is to maybe say, that’s all they can play—and black people can do whatever they want"! He understood the circular nature of the question, and by personalizing it, made it clear that what the journalist intended as a compliment, was nothing of the kind.

Rice Miller, better known as "Sonny Boy Williamson no. 2" co-opted the pseudonym from the original Sonny Boy Williamson, a contemporary whose real name was John Lee Williamson, exploiting it for a buck, claiming to be the original. Decades after both were gone, Miller’s ruse was forgiven and even laughed about. It was clear that, no matter what the alias, he was one of the finest singer/harmonica players and songwriters the blues ever produced. But then Sonny Boy no.2 had what Muhammad Ali used to call, "the right complexion and the right connection," sufficient to satisfy the critic's preconceptions regarding the authentic “Black” and "Blues" experience.

By the time that blues musicians like Sonny Boy crossed over to white audiences, they realized that their new fans had expectations that needed to be fulfilled. And so they lied about their age, claiming to be born before the dawn of the twentieth century, making them somehow more authentic—the last of a dying breed—a connection to our past, purer and untainted by the commercialism of our culture. These new fans were privileged by birth "Aesthetic Socialists" seeking the truth beyond the money. Only then could the music be properly appreciated, listening as much with their eyes as their ears. The musicians, like all instinctive Capitalists, just wanted to get paid for their efforts.

In the song “The Pilgrim,” Kris Kristofferson wrote the lyrics; “He’s a poet, He's a picker, He's a prophet, He's a pusher, He's a pilgrim and a preacher and a problem when he's stoned. He's a walking contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction, taking every wrong direction on his lonely way back home".

Kristofferson, a former Rhodes Scholar, golden gloves boxer, and aspiring country singer, took some Johnny Cash, his own gifts as a poet, and a love for country music and reinvented himself. Like Lowell George, and a whole bunch of other gifted artists, known and unknown, he proved that, in spite of how, when and where we're born, we are what we choose to be.

Mark Magula

In the song “The Pilgrim,” Kris Kristofferson wrote the lyrics; “He’s a poet, He's a picker, He's a prophet, He's a pusher, He's a pilgrim and a preacher and a problem when he's stoned. He's a walking contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction, taking every wrong direction on his lonely way back home".

Kristofferson, a former Rhodes Scholar, golden gloves boxer, and aspiring country singer, took some Johnny Cash, his own gifts as a poet, and a love for country music and reinvented himself. Like Lowell George, and a whole bunch of other gifted artists, known and unknown, he proved that, in spite of how, when and where we're born, we are what we choose to be.

Mark Magula