The Birth of the Jazz Guitarist

After years of playing nothing but rock and roll, and its related forms, I found myself hanging with a number of good jazz musicians. Within my chosen idiom I was a hotshot, outside of it, I was a complete amateur. It was an unpleasant wake-up call, one of many to come throughout the course of my life. I didn't like it, I'm not sure anyone ever does.

Maybe, that's why we humans have a tendency to retreat to a safe haven. "Home is where the heart is." or, at least, the place where we're most likely to find refuge from dissenting opinion. But, without the storms of life that come in the form of other folks who think differently, we'd remain static, frozen in a very small world where we are kings of nothing much.

So, I ventured forth into the land of jazz--where the notes flowed like wine and the chords passed by with the speed of thought--which may have been slower than one might think, depending upon who was doing the thinking and the playing.

It was, however, very fast for a guitarist raised on the blues and the 1-4-5 progression. Eventually, the 1-4-5 gave way to the 2-5-1 and then multiple 2-5-1's. Shifting harmonic sands opened before me like treacherous sinkholes, threatening to swallow me and my pitiful guitar, but I stayed the course. "How brave of me." I thought. Such is the nature of the musical mind, always existing on the periphery of the sociopath and self-delusion!

My first act of idolatry was to find an idol to worship, which turned out to be Joe Pass. At first, I had no idea about what he was doing, it was apparent nonetheless, that he did it really, really well. He spun legato lines from his axe that made the head spin. He also knew at least a billion chords, and a billion is obviously a lot. If this seems like an exaggeration, it is, but, only slightly.

I would listen intently, thinking to myself "What the hell is that?" and then go back to listening, hoping that I would, somehow absorb some of it through osmosis. Not much of it made sense, but it offered a high standard to aspire to, one with a voluminous note count.

In time, I found other idols, Wes Montgomery, Tal Farlow, Kenny Burrell, Jim Hall, Barney Kessel, Herb Ellis, and then a younger generation, Larry Coryell and John McLaughlin, the Hendrix and Clapton of that new music that would eventually be called Jazz-rock or Fusion, long before anyone new what to call it. There were others as well, but these were, for me, the essentials, the pantheon.

Over time, I began to listen to the music as "music" instead of as a series of chord changes and hot licks. The beauty of a Gershwin tune, Rodgers and Hart, Tin Pan Alley and Duke Ellington, they formed the heart of it all. Singers and songs, musicians that played like singers; Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong, and singers that sang like instrumentalists; Sinatra, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald, each gave me back the music that lurked just beneath the licks. It was only then, that it all began to make sense, and the rest came naturally.

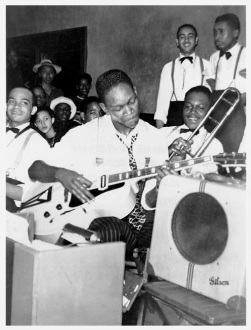

For multiple generations of guitarists, jazz guitar was the aforementioned players. All of them, however, followed in the aftermath of essentially one man, Charlie Christian, who almost singlehandedly ushered in the age of electricity. He wasn't the first to plug in, but he was, without question, the most influential. He changed its sound and its language, while moving the guitar from the back of the bus with the rhythm section to a place that challenged the horn players on the front line. He was the Rosa Parks of guitar players.

His was a musical and technical revolution that altered the guitarist’s toolkit and transformed the way the instrument was played. Christian’s impact was so immediate that it compelled untold numbers of potential horn players to pick up the guitar instead, altering the course of music history in the process.

Horn players and pianists had dominated the sound of jazz, the guitar, by comparison was too soft spoken to challenge the brass section and too limited harmonically to replace the piano as the instrument of choice for accompaniment. But, wed the guitar to a speaker and the landscape was forever changed.

There were other players of significance before Christian, Django Reinhardt, the Gypsy phenomenon, Eddie Lang, Bing Crosby’s personal accompanist and a virtuoso in his own right, and the extraordinary Lonnie Johnson. All, however, came a decade too early.

By the time Charlie Christian emerged, the amplified guitar was the futuristic new kid on the block, swing was the music of choice, while big bands delivered the message to dance-crazed American and European audiences. Recording techniques had significantly improved, making records and radio a conduit to the world. World War II, however, had depleted the rank and file of the big bands, while the demand for plastics and other materials made recording new music increasingly difficult.

Maybe, that's why we humans have a tendency to retreat to a safe haven. "Home is where the heart is." or, at least, the place where we're most likely to find refuge from dissenting opinion. But, without the storms of life that come in the form of other folks who think differently, we'd remain static, frozen in a very small world where we are kings of nothing much.

So, I ventured forth into the land of jazz--where the notes flowed like wine and the chords passed by with the speed of thought--which may have been slower than one might think, depending upon who was doing the thinking and the playing.

It was, however, very fast for a guitarist raised on the blues and the 1-4-5 progression. Eventually, the 1-4-5 gave way to the 2-5-1 and then multiple 2-5-1's. Shifting harmonic sands opened before me like treacherous sinkholes, threatening to swallow me and my pitiful guitar, but I stayed the course. "How brave of me." I thought. Such is the nature of the musical mind, always existing on the periphery of the sociopath and self-delusion!

My first act of idolatry was to find an idol to worship, which turned out to be Joe Pass. At first, I had no idea about what he was doing, it was apparent nonetheless, that he did it really, really well. He spun legato lines from his axe that made the head spin. He also knew at least a billion chords, and a billion is obviously a lot. If this seems like an exaggeration, it is, but, only slightly.

I would listen intently, thinking to myself "What the hell is that?" and then go back to listening, hoping that I would, somehow absorb some of it through osmosis. Not much of it made sense, but it offered a high standard to aspire to, one with a voluminous note count.

In time, I found other idols, Wes Montgomery, Tal Farlow, Kenny Burrell, Jim Hall, Barney Kessel, Herb Ellis, and then a younger generation, Larry Coryell and John McLaughlin, the Hendrix and Clapton of that new music that would eventually be called Jazz-rock or Fusion, long before anyone new what to call it. There were others as well, but these were, for me, the essentials, the pantheon.

Over time, I began to listen to the music as "music" instead of as a series of chord changes and hot licks. The beauty of a Gershwin tune, Rodgers and Hart, Tin Pan Alley and Duke Ellington, they formed the heart of it all. Singers and songs, musicians that played like singers; Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong, and singers that sang like instrumentalists; Sinatra, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald, each gave me back the music that lurked just beneath the licks. It was only then, that it all began to make sense, and the rest came naturally.

For multiple generations of guitarists, jazz guitar was the aforementioned players. All of them, however, followed in the aftermath of essentially one man, Charlie Christian, who almost singlehandedly ushered in the age of electricity. He wasn't the first to plug in, but he was, without question, the most influential. He changed its sound and its language, while moving the guitar from the back of the bus with the rhythm section to a place that challenged the horn players on the front line. He was the Rosa Parks of guitar players.

His was a musical and technical revolution that altered the guitarist’s toolkit and transformed the way the instrument was played. Christian’s impact was so immediate that it compelled untold numbers of potential horn players to pick up the guitar instead, altering the course of music history in the process.

Horn players and pianists had dominated the sound of jazz, the guitar, by comparison was too soft spoken to challenge the brass section and too limited harmonically to replace the piano as the instrument of choice for accompaniment. But, wed the guitar to a speaker and the landscape was forever changed.

There were other players of significance before Christian, Django Reinhardt, the Gypsy phenomenon, Eddie Lang, Bing Crosby’s personal accompanist and a virtuoso in his own right, and the extraordinary Lonnie Johnson. All, however, came a decade too early.

By the time Charlie Christian emerged, the amplified guitar was the futuristic new kid on the block, swing was the music of choice, while big bands delivered the message to dance-crazed American and European audiences. Recording techniques had significantly improved, making records and radio a conduit to the world. World War II, however, had depleted the rank and file of the big bands, while the demand for plastics and other materials made recording new music increasingly difficult.

Eventually the war ended, America moved into its most prosperous age and electric guitarists began to take the instrument to places previously off limits to its acoustic forerunner. Most of them came of age at the peak of the swing era, just as multiple other musical and technical innovations were beginning to happen.

As the swing craze approached its end and the Big Bands gave way to smaller ensembles, the blues increasingly formed the foundation of the music. Songs with simpler rhythms and chord structures replaced those that came out of "Tin Pan Alley" and Rhythm & Blues, sometimes called "jump band music" was born. It was a meeting of foot tapping, swinging rhythm, mixed with the blues.

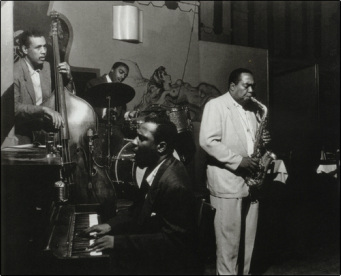

But as popular music was becoming simpler, a less commercial, increasingly complex music was emerging. One with altered harmonies that were considered atonal and a rhythm that was not only difficult to dance to, it was intended to be listened to as art!

The new music began it's gestation in the small clubs that functioned like laboratories where musicians of a parallel bent played in all-night jam sessions. They shared radical sounding chords and rhythms and found fresh ways to negotiate the challenging new musical framework that was beginning to take shape. Blistering tempos separated the pretenders and the traditionalists from the young radicals, if you couldn't hang you were unceremoniously forced off the band-stand by the sheer complexity of the music being played. It was the beginning of Modern Jazz, sometimes called Be-bop, a term coined by Dizzy Gillespie, the great trumpet virtuoso, and one of the music's most important architects. The term was also attributed to Charlie Christian, who spent his off hours from the Benny Goodman band playing with Gillespie, Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk at "Minton's Playhouse," the legendary after-hours club that was for jazz musicians what the "Algonquin Round Table" was for the young cultural and literary lions of the 1920's.

Be-bop took swing’s rhythms and deconstructed them. Removing the strong rhythmic pulse, replacing it with a less incessant beat. The intent was to free the soloist from the restrictive bonds of dance-based music, enabling them to move freely through the song's harmonic framework. Musicians used flatted fifth and ninth intervals, augmented and diminished sounds as more than just passing chords to color the music. Instead, they became an intrinsic part of the music's structure, adding to the modernity of its sound. It was the auditory equivalent of Picasso or Van Gogh, laying the foundation for Jazz's march towards a Jackson Pollock like freedom with Ornette Coleman.

Jazz was following the same path as other art forms, pushing the boundaries from freedom to anarchy and back, and as the music became less familiar it became less popular. The band was no longer primarily a vehicle for dancers, but became a place where challenging music was intended for listening. The audience was a secondary consideration, they were invited guests, paying for the right to be observers to the act of creation.

Be-bop's free floating virtuosity, disconnected from commercial restraints, was also the impetus for a group of young literary radicals called "The Beats." Jack Kerouac, Allan Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs took the jazz lifestyle, the music's rhythms and it's self-conscious angularity as a cue to explore the possibility of stream of consciousness poetry and prose. Like all art forms, jazz was feeding from, as well as feeding into, the broad cross-cultural creativity that was American life in the post-war years.

As the swing craze approached its end and the Big Bands gave way to smaller ensembles, the blues increasingly formed the foundation of the music. Songs with simpler rhythms and chord structures replaced those that came out of "Tin Pan Alley" and Rhythm & Blues, sometimes called "jump band music" was born. It was a meeting of foot tapping, swinging rhythm, mixed with the blues.

But as popular music was becoming simpler, a less commercial, increasingly complex music was emerging. One with altered harmonies that were considered atonal and a rhythm that was not only difficult to dance to, it was intended to be listened to as art!

The new music began it's gestation in the small clubs that functioned like laboratories where musicians of a parallel bent played in all-night jam sessions. They shared radical sounding chords and rhythms and found fresh ways to negotiate the challenging new musical framework that was beginning to take shape. Blistering tempos separated the pretenders and the traditionalists from the young radicals, if you couldn't hang you were unceremoniously forced off the band-stand by the sheer complexity of the music being played. It was the beginning of Modern Jazz, sometimes called Be-bop, a term coined by Dizzy Gillespie, the great trumpet virtuoso, and one of the music's most important architects. The term was also attributed to Charlie Christian, who spent his off hours from the Benny Goodman band playing with Gillespie, Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk at "Minton's Playhouse," the legendary after-hours club that was for jazz musicians what the "Algonquin Round Table" was for the young cultural and literary lions of the 1920's.

Be-bop took swing’s rhythms and deconstructed them. Removing the strong rhythmic pulse, replacing it with a less incessant beat. The intent was to free the soloist from the restrictive bonds of dance-based music, enabling them to move freely through the song's harmonic framework. Musicians used flatted fifth and ninth intervals, augmented and diminished sounds as more than just passing chords to color the music. Instead, they became an intrinsic part of the music's structure, adding to the modernity of its sound. It was the auditory equivalent of Picasso or Van Gogh, laying the foundation for Jazz's march towards a Jackson Pollock like freedom with Ornette Coleman.

Jazz was following the same path as other art forms, pushing the boundaries from freedom to anarchy and back, and as the music became less familiar it became less popular. The band was no longer primarily a vehicle for dancers, but became a place where challenging music was intended for listening. The audience was a secondary consideration, they were invited guests, paying for the right to be observers to the act of creation.

Be-bop's free floating virtuosity, disconnected from commercial restraints, was also the impetus for a group of young literary radicals called "The Beats." Jack Kerouac, Allan Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs took the jazz lifestyle, the music's rhythms and it's self-conscious angularity as a cue to explore the possibility of stream of consciousness poetry and prose. Like all art forms, jazz was feeding from, as well as feeding into, the broad cross-cultural creativity that was American life in the post-war years.

It was in this crossfire of dance-based swing music and the revolution of Be-bop that the greatest generation of jazz guitarists came of age. From about 1940, and for the next fifty years, they dominated their instrument and their chosen idiom the way few others ever have.

There were other insurgents as well. T Bone Walker was a fellow traveler and sometime playing partner with Christian before either man became famous. He set in motion his own revolution on guitar. Walker started his career as a musical apprentice with one of early blues music’s greatest iconoclasts, "Blind Lemon Jefferson," in the 1920's, making his first record in 1929.

Walker was to the blues what Christian was to jazz. He was also a fine singer, songwriter and unparalleled showman who electrified crowds, duck walking with his guitar behind his head before anyone had an inkling about Chuck Berry. Where Christian was a pivotal part of the band, T Bone Walker was front and center; singer, soloist and bandleader.

Absent some ridiculous hyperbole it would be difficult to overstate their influence on the cult of the electric guitar. Players as disparate as Merle Travis, James Burton, Buddy Guy, Chuck Berry and Jeff Beck borrowed from both. Just listen to Bill Haley and the Comets "Rock Around the Clock" and you'll hear Mr. Christian and T Bone all through its iconic solo, that would be true of just about every other jazz, blues and country record as well, including Elvis.

When you get down to the essentials, if you've plugged a guitar into an amp, you owe at least some portion of a debt to these pioneers. And, it would seem to me, the best way to repay it would be to play the music, play it well, and never forget where you got it from! To do less than that would be heresy, if not exactly, then close enough.

Mark Magula

There were other insurgents as well. T Bone Walker was a fellow traveler and sometime playing partner with Christian before either man became famous. He set in motion his own revolution on guitar. Walker started his career as a musical apprentice with one of early blues music’s greatest iconoclasts, "Blind Lemon Jefferson," in the 1920's, making his first record in 1929.

Walker was to the blues what Christian was to jazz. He was also a fine singer, songwriter and unparalleled showman who electrified crowds, duck walking with his guitar behind his head before anyone had an inkling about Chuck Berry. Where Christian was a pivotal part of the band, T Bone Walker was front and center; singer, soloist and bandleader.

Absent some ridiculous hyperbole it would be difficult to overstate their influence on the cult of the electric guitar. Players as disparate as Merle Travis, James Burton, Buddy Guy, Chuck Berry and Jeff Beck borrowed from both. Just listen to Bill Haley and the Comets "Rock Around the Clock" and you'll hear Mr. Christian and T Bone all through its iconic solo, that would be true of just about every other jazz, blues and country record as well, including Elvis.

When you get down to the essentials, if you've plugged a guitar into an amp, you owe at least some portion of a debt to these pioneers. And, it would seem to me, the best way to repay it would be to play the music, play it well, and never forget where you got it from! To do less than that would be heresy, if not exactly, then close enough.

Mark Magula

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|