King Arthur, Pelagius and Original Sin

After a long, long day of earning my keep (Yes, dear readers, I must make a living. Weekly Southern Arts simply doesn’t pay the bills!), I was relaxing at home. My wife had already gone to bed and I was flipping channels on the TV when I came across the Clive Owen flick, “King Arthur.” The movie is a re-telling of the Arthurian legend with Arthur portrayed as a half-Roman, half-Briton centurion defending Hadrian’s Wall against the “Woads” (the native Picts) at the time of Rome’s abandonment of Britain on or around 457 AD.

I had seen the movie before, which was a reason to watch it again. I don’t know about you but, when I’m tired, I don’t want to watch something that requires me to pay too much attention!

So, I was watching the movie and was reminded that Clive Owen’s character, Arthur, was supposedly taught by the Briton Monk, Pelagius. This, of course, could not be true, since Pelagius probably died sometime between 418 and 425 AD. However, it did cause me to think about Pelagius for the first time in a while—and what I wanted to write about.

Pelagius was Briton, which means that he was a Celt from Britain who lived in the Roman-controlled area south of Hadrian’s Wall. He was well educated and lived for some twenty-five years in Rome where he may have gone to study law. However, he had a radical conversion experience while there and became a Christian ascetic. Although apparently a compelling figure who collected many followers, he was never an ordained minister, rather, he was a pious layman.

Hearing Pelagius’ name mentioned in the movie reminded me of the epic theological battle waged by Augustine, the Bishop of Hippo, and Jerome, the author of the Latin Vulgate Bible, against Pelagius in the 4th and 5th Centuries. Although Augustine noted that Pelagius was a pious, holy man, he vigorously attacked Pelagius’ theology as it pertained to Augustine’s notions of Original Sin and Predestination. (To be fair, Pelagius made the first move when he denounced Augustine’s theology as being akin to that of the pagan Manicheans.)

The Manicheans, dualists who saw the world as being divided into the competing kingdoms of Light and Darkness, believed the spirit of man to be divine and the rest of man to be utterly corrupted by “Darkness.” Its primary feature was salvation through knowledge, a concept which it shared with the much older Gnostic religions. Because of this shared concept of salvation, I thought the Manicheans to also share the Gnostic’s oft-held belief that, since the spirit of man was holy and the flesh was corrupt, the flesh could seek after its own lusts while the spirit was engaged in divine pursuits. This feature of Gnosticism is alive and well in our culture today and is, perhaps, best evidenced by the popular, if simpleminded, clichés spouted by movie stars and others who trade on celebrity. “Hey, I’m spiritual, man.” they assure one and all while doing whatever they want with whomever they want. However, the Manicheans, in fact, esteemed a rigorously ascetic lifestyle, at least for their holiest adherents, the “Bearers of Light,” eschewing all manner of sexual relations and, apparently, even restricting speech.

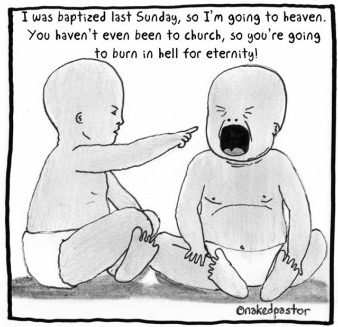

What got to Pelagius was a statement read by one of Augustine’s disciples, “"Give me what you command and command what you will." This statement is from Augustine’s “Confessions” and Pelagius, apparently, believed this and other Augustinian teachings contradicted the traditional Christian understanding of grace and free will, that is, such a verse turned man into a mere robot. This prompted him to write his “Commentary on the Pauline Epistles.” In his commentary, Pelagius laid out his objections to the Augustinian doctrines of the inherited guilt of original sin, rigid predestination, and the necessity of baptism to spare infants from hell.

I had seen the movie before, which was a reason to watch it again. I don’t know about you but, when I’m tired, I don’t want to watch something that requires me to pay too much attention!

So, I was watching the movie and was reminded that Clive Owen’s character, Arthur, was supposedly taught by the Briton Monk, Pelagius. This, of course, could not be true, since Pelagius probably died sometime between 418 and 425 AD. However, it did cause me to think about Pelagius for the first time in a while—and what I wanted to write about.

Pelagius was Briton, which means that he was a Celt from Britain who lived in the Roman-controlled area south of Hadrian’s Wall. He was well educated and lived for some twenty-five years in Rome where he may have gone to study law. However, he had a radical conversion experience while there and became a Christian ascetic. Although apparently a compelling figure who collected many followers, he was never an ordained minister, rather, he was a pious layman.

Hearing Pelagius’ name mentioned in the movie reminded me of the epic theological battle waged by Augustine, the Bishop of Hippo, and Jerome, the author of the Latin Vulgate Bible, against Pelagius in the 4th and 5th Centuries. Although Augustine noted that Pelagius was a pious, holy man, he vigorously attacked Pelagius’ theology as it pertained to Augustine’s notions of Original Sin and Predestination. (To be fair, Pelagius made the first move when he denounced Augustine’s theology as being akin to that of the pagan Manicheans.)

The Manicheans, dualists who saw the world as being divided into the competing kingdoms of Light and Darkness, believed the spirit of man to be divine and the rest of man to be utterly corrupted by “Darkness.” Its primary feature was salvation through knowledge, a concept which it shared with the much older Gnostic religions. Because of this shared concept of salvation, I thought the Manicheans to also share the Gnostic’s oft-held belief that, since the spirit of man was holy and the flesh was corrupt, the flesh could seek after its own lusts while the spirit was engaged in divine pursuits. This feature of Gnosticism is alive and well in our culture today and is, perhaps, best evidenced by the popular, if simpleminded, clichés spouted by movie stars and others who trade on celebrity. “Hey, I’m spiritual, man.” they assure one and all while doing whatever they want with whomever they want. However, the Manicheans, in fact, esteemed a rigorously ascetic lifestyle, at least for their holiest adherents, the “Bearers of Light,” eschewing all manner of sexual relations and, apparently, even restricting speech.

What got to Pelagius was a statement read by one of Augustine’s disciples, “"Give me what you command and command what you will." This statement is from Augustine’s “Confessions” and Pelagius, apparently, believed this and other Augustinian teachings contradicted the traditional Christian understanding of grace and free will, that is, such a verse turned man into a mere robot. This prompted him to write his “Commentary on the Pauline Epistles.” In his commentary, Pelagius laid out his objections to the Augustinian doctrines of the inherited guilt of original sin, rigid predestination, and the necessity of baptism to spare infants from hell.

Baptism of infants, by the way, always has struck me as a particularly stupid thing to do. I don’t suppose that it hurts babies, but an unthinking, unknowing dunking or sprinkling is of no more value than a bath. However, if you think like Augustine, that all of mankind is born into sin, and if you also believe that baptism is essential to salvation, then you would simply be irresponsible if you didn’t baptize your child as soon as possible.

I am neither an historian nor a theologian; I’m just a guy who tries to live a Christian life in a world of conflicting pressures. Being raised, as I was, in Baptist and Pentecostal churches, I absorbed a generally Augustinian view of the fall of man, original sin, etc. without actually thinking too much about it. My focus was mostly on the practical application of Christ’s teachings on my life and that of my family and church community. However, over the years, I have had many speculative discussions with friends and family members regarding these “larger” issues affecting the Christian faith and it was during those discussions that I first became aware of Pelagius, and even older, patristic understandings of these topics.

My first attempt to gain understanding of the church’s historic foundations was, ironically, to read Augustine some years back. Augustine, of course, is a seminal figure in the modern church. In his battle to overcome Pelagius’ objections to his theology, he not only prevailed, but actually succeeded in having Pelagius declared a heretic. For this reason, much of the Christian Church, at least in the West, has remained ignorant of Pelagius’ teachings for the last fifteen hundred years. As I read Augustine, I became troubled by the notion of original sin, as he explained it, but I didn’t immediately know why. After all, this notion of mankind being fundamentally flawed seemed, by observation, to be pretty accurate!

When I looked for those offering an alternative to Augustine, an alternative that I sought merely to get both sides of the issue, it was then that I discovered Pelagius, Origen and other early teachers who did not, in fact, share Augustine’s views. I now find Pelagius’ notion that Original Sin is irrational to be compelling; however, it took some time to overcome my natural tendency to adhere to the unthinking “absolutes” of my youth. Again, I am no theologian, but this is what I have come to, as a result of reading these earlier fathers of the faith:

First, Original Sin, as espoused by Augustine, was a new concept not found by earlier Jewish and Christian theologians. Pelagius thought this notion of Augustine’s to be a holdover from Augustine’s pre-Christian Manichean beliefs. Even though Augustine brilliantly opposed the Manicheans after his conversion to Christianity, Pelagius saw in Augustine’s teachings a tendency towards an irrational system of belief—a belief system that said God created man in holiness, permitted the first man to become a sinner, then cursed all of mankind to be held to that sin, was prepared to condemn all men for that sin, offered a way out for those whom He chose (predestined) through the saving work of Jesus Christ, and punished everyone else for having been born into sin.

This is, of course, an overly simplified version of Augustine’s beliefs. However, what becomes clear in this version of events is that God is a monstrously unjust figure. He sets up mankind for failure and then saves those whom He favors. Nowhere in this account is man actually able to act on his own free will.

I am neither an historian nor a theologian; I’m just a guy who tries to live a Christian life in a world of conflicting pressures. Being raised, as I was, in Baptist and Pentecostal churches, I absorbed a generally Augustinian view of the fall of man, original sin, etc. without actually thinking too much about it. My focus was mostly on the practical application of Christ’s teachings on my life and that of my family and church community. However, over the years, I have had many speculative discussions with friends and family members regarding these “larger” issues affecting the Christian faith and it was during those discussions that I first became aware of Pelagius, and even older, patristic understandings of these topics.

My first attempt to gain understanding of the church’s historic foundations was, ironically, to read Augustine some years back. Augustine, of course, is a seminal figure in the modern church. In his battle to overcome Pelagius’ objections to his theology, he not only prevailed, but actually succeeded in having Pelagius declared a heretic. For this reason, much of the Christian Church, at least in the West, has remained ignorant of Pelagius’ teachings for the last fifteen hundred years. As I read Augustine, I became troubled by the notion of original sin, as he explained it, but I didn’t immediately know why. After all, this notion of mankind being fundamentally flawed seemed, by observation, to be pretty accurate!

When I looked for those offering an alternative to Augustine, an alternative that I sought merely to get both sides of the issue, it was then that I discovered Pelagius, Origen and other early teachers who did not, in fact, share Augustine’s views. I now find Pelagius’ notion that Original Sin is irrational to be compelling; however, it took some time to overcome my natural tendency to adhere to the unthinking “absolutes” of my youth. Again, I am no theologian, but this is what I have come to, as a result of reading these earlier fathers of the faith:

First, Original Sin, as espoused by Augustine, was a new concept not found by earlier Jewish and Christian theologians. Pelagius thought this notion of Augustine’s to be a holdover from Augustine’s pre-Christian Manichean beliefs. Even though Augustine brilliantly opposed the Manicheans after his conversion to Christianity, Pelagius saw in Augustine’s teachings a tendency towards an irrational system of belief—a belief system that said God created man in holiness, permitted the first man to become a sinner, then cursed all of mankind to be held to that sin, was prepared to condemn all men for that sin, offered a way out for those whom He chose (predestined) through the saving work of Jesus Christ, and punished everyone else for having been born into sin.

This is, of course, an overly simplified version of Augustine’s beliefs. However, what becomes clear in this version of events is that God is a monstrously unjust figure. He sets up mankind for failure and then saves those whom He favors. Nowhere in this account is man actually able to act on his own free will.

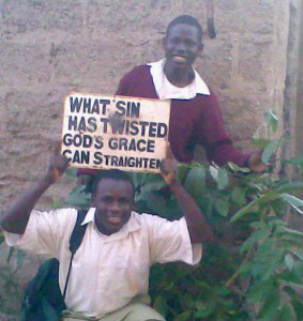

Pelagius, by contrast, believed in a rational approach that said, in effect, God made man to be holy. It is within the capacity of man to, in fact, live a holy life, as witnessed by the Biblical Patriarchs and any number of moral, generous, loving pagans. Because of the fall of the first man (Adam), innocence has been lost and a sin nature has entered into humankind. However, each person has the capacity to make moral judgments about their behavior and can, however theoretically, lead a holy life. I admit that, at this point, such a holy existence seems entirely theoretical. As the Apostle Paul said, “For all have sinned and come short of the glory of God.” I would not dispute this statement! Nonetheless, for man to have a free will, the capacity to live a holy life, quite apart from any knowledge of the bible would, it seems to me, have to exist.

Examining this concept further, it becomes apparent that the fall of man described in Genesis 3 does not pertain to a moralistic failing, as imagined by Augustine. Rather, Adam and Eve’s disobedience is a relational failure. They have willfully separated themselves from the living relationship that they enjoyed with God and their spirits have withered as a result, since their spirits were imparted to them by God who is the Living Spirit. It is this separation, this breaking of fellowship with God, that leads to death and it is death, according to Paul, that is the power of sin.

Let’s look at the other primary scripture used by Augustine, Romans 5:12-14, “Therefore, just as through one man sin entered into the world, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men, because all sinned—for until the Law sin was in the world, but sin is not imputed when there is no law. Nevertheless death reigned from Adam until Moses, even over those who had not sinned in the likeness of the offense of Adam, who is a type of Him who was to come.” Notice that Paul declares sin to not be imputed without the existence of law. However, death continued unabated with or without the law. Clearly, the spiritual death experienced by Adam as a result of sinning continued as his descendants also experienced the same spiritual death and separation from God’s spirit and, as a result, continued to sin.

Sin came first, but it is death that empowers sin in this world. God intended us to enjoy a destiny of loving relationship with Him and loving relationship with our fellow man. As a result of sin, death has been given power over mankind and, indeed, the entire world. The God-ordained destiny for mankind has been perverted to one of self seeking after security and comfort rather than selfless love for others. This is quite different from the moralistic, Platonic vision of Augustine. He sought to explain the fall of man in terms of a moral duality, right and wrong, and missed, in my opinion, the relational aspect of the fall.

Examining this concept further, it becomes apparent that the fall of man described in Genesis 3 does not pertain to a moralistic failing, as imagined by Augustine. Rather, Adam and Eve’s disobedience is a relational failure. They have willfully separated themselves from the living relationship that they enjoyed with God and their spirits have withered as a result, since their spirits were imparted to them by God who is the Living Spirit. It is this separation, this breaking of fellowship with God, that leads to death and it is death, according to Paul, that is the power of sin.

Let’s look at the other primary scripture used by Augustine, Romans 5:12-14, “Therefore, just as through one man sin entered into the world, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men, because all sinned—for until the Law sin was in the world, but sin is not imputed when there is no law. Nevertheless death reigned from Adam until Moses, even over those who had not sinned in the likeness of the offense of Adam, who is a type of Him who was to come.” Notice that Paul declares sin to not be imputed without the existence of law. However, death continued unabated with or without the law. Clearly, the spiritual death experienced by Adam as a result of sinning continued as his descendants also experienced the same spiritual death and separation from God’s spirit and, as a result, continued to sin.

Sin came first, but it is death that empowers sin in this world. God intended us to enjoy a destiny of loving relationship with Him and loving relationship with our fellow man. As a result of sin, death has been given power over mankind and, indeed, the entire world. The God-ordained destiny for mankind has been perverted to one of self seeking after security and comfort rather than selfless love for others. This is quite different from the moralistic, Platonic vision of Augustine. He sought to explain the fall of man in terms of a moral duality, right and wrong, and missed, in my opinion, the relational aspect of the fall.

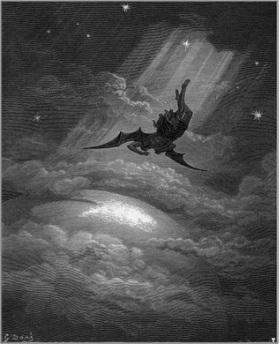

Further, Paul makes quite clear that there is another, active agent who willfully and cleverly seeks to deceive mankind and keep him from relationship with God. That agent is the Devil, Satan. Although created by God, he chose to rebel against his Creator and, having lost that battle, defeated but unbowed, has continued to attempt further disruptions of God’s Kingdom. It was he who deceived Eve in the Garden of Eden and it was he whom Paul spoke of at length as the enemy of man.

Given this formidable enemy, given that our spirits were dead in sin, we were in desperate need of assistance. It was for this reason that Jesus humbled himself and came to earth in the form of a man, receiving in himself the failings of all men and it is because of His victory over death, the power of sin, that sin no longer holds sway over those who trust in Him. We needed help and He gave us His only begotten Son so that whosoever believes in Him will be saved from the spiritual death that for so long has separated man from God. Through Jesus, the means of reconciliation to our Creator has been provided.

So, leaping off from this point, I find that I believe the following: If man does have a free will, and is NOT burdened by original sin, then it is man’s responsibility, not God’s, when he sins. Man could have avoided sin, but under fear of death, made the choice to pursue it. As such, man has come under the burden of sin and is in need of a savior. God, by His grace, has made a way for us to return to that place of holiness through the sacrificial atoning actions of Jesus Christ. Jesus has become the mediator of reconciliation between God and His creation.

We are free to recognize our need for assistance, and are free to accept the salvation offered by God through Jesus Christ. However, the act of justification is not ours. When we recognize our need for a savior, it is the Holy Spirit who brings us to that place of conviction. When we find that we believe in the salvation provided by Jesus, it is the Holy Spirit who gives us that measure of faith, and when we repent of our sins and confess Jesus as our very necessary Savior and Lord, it is the Holy Spirit who declares us justified. We do not make ourselves justified by our own actions. God alone is sovereign and He declares us justified on the basis of our accepting His gracious gift of salvation.

Given this formidable enemy, given that our spirits were dead in sin, we were in desperate need of assistance. It was for this reason that Jesus humbled himself and came to earth in the form of a man, receiving in himself the failings of all men and it is because of His victory over death, the power of sin, that sin no longer holds sway over those who trust in Him. We needed help and He gave us His only begotten Son so that whosoever believes in Him will be saved from the spiritual death that for so long has separated man from God. Through Jesus, the means of reconciliation to our Creator has been provided.

So, leaping off from this point, I find that I believe the following: If man does have a free will, and is NOT burdened by original sin, then it is man’s responsibility, not God’s, when he sins. Man could have avoided sin, but under fear of death, made the choice to pursue it. As such, man has come under the burden of sin and is in need of a savior. God, by His grace, has made a way for us to return to that place of holiness through the sacrificial atoning actions of Jesus Christ. Jesus has become the mediator of reconciliation between God and His creation.

We are free to recognize our need for assistance, and are free to accept the salvation offered by God through Jesus Christ. However, the act of justification is not ours. When we recognize our need for a savior, it is the Holy Spirit who brings us to that place of conviction. When we find that we believe in the salvation provided by Jesus, it is the Holy Spirit who gives us that measure of faith, and when we repent of our sins and confess Jesus as our very necessary Savior and Lord, it is the Holy Spirit who declares us justified. We do not make ourselves justified by our own actions. God alone is sovereign and He declares us justified on the basis of our accepting His gracious gift of salvation.

I think that this version of Christian theology offers the advantage of rationality—something that I believe God desires in us and something that He exemplifies in His Word. Does this change our experience of sin and salvation? No, not really. What it does change is our understanding of the nature of God and the freedom that He bequeathed to us. He is NOT an irrational judge who set us up for a fall and then condemned us for it. He is a loving and merciful Father who desires that we come to Him of our own free will. (Nonetheless, He is willing to accept our decision to reject Him if that is our wish.) What a difference this makes in understanding His great love! How He yearns for us to come to Him. He, who is love personified, desires that we have an intimate relationship with Him, as a child to their father, and like a loving father, has made provision for same through Jesus Christ.

Hallelujah!

As I read the surviving works of the early church fathers, I am struck at the wide variety of views provided on the subjects of sin and salvation. At this point, two thousand years removed from the church’s founding, it is easy to assume that whatever is said of a Sunday in church must be so. After all, if it was wrong someone would have fixed it by now, right? However, these issues are, in fact, not as settled as one might think.

There is, I believe, a growing restlessness within the nominally Christian culture of the West and a consequent challenge to the status quo in churches. People of good character, earnestly seeking truth, read the Nicene Creed, Augustine’s works, or simply the “statements of faith” at their local church and come to the conclusion that their God is an irrational brute condemning them to Hell for simply having been born. If the church won’t face up to the irrational aspects of their traditions, they will lose these people. That would be a tragedy for all concerned. Lost people really do need Jesus as their Savior and the church needs to present the faith in a compelling and rational manner. “God is not a God of disorder” people often say. If this is so, and I believe it is so, then a pre-Augustinian theology would seem to be in order.

While I have noted some things that I think are problematic in Augustine’s work, I cannot point to much criticism of Pelagias’ work since most of it was destroyed as a result of him being declared a heretic. Nonetheless, reading what Clement, Origen and others who preceded him had to say it becomes clear that the position reportedly held by him was more in keeping with the early church beliefs than was Augustine’s invention of Original Sin.

Clive Owen’s character, Arthur, may not have actually learned from Pelagius, but I am grateful to him for reminding me of this early church pioneer.

Thomas A. Hall

Addendum:

A week or so after having first published this article, my father, who was concerned enough about what I stated as my position to quiz me about it, sent me an email noting a recent controversy in Southern Baptist circles (He is a deacon in a Southern Baptist Church). That controversy resulted from a “Statement of Belief” authored by several prominent leaders of the Southern Baptist Convention and may be found at this link: http://theaquilareport.com/non-calvinist-southern-baptists-issue-statement-of-beliefs-by-staff/

If the reader does follow this link, they will find that the “Statement of Belief” is explicitly rejecting Calvinism—or Augustinianism, if you will.

As it turns out, and I had no idea of it when I started this investigation, the Southern Baptist view has been generally that of a “Semi-Pelagian” nature for quite some time. Having read the “Statement of Belief” and also having read an excellent discussion of it at this site: http://whytheology.wordpress.com/tag/baptist-faith-and-message/ , I find that my hard work of discovery was merely to define a theology that has been a major theme of Baptist thought for centuries. Oh well, however one gets there, it is good to get to an understanding of these matters!

It appears that my article describes, more or less, a “Semi-Pelagian” point of view. This term, “Semi-Pelagian” has been used to dismiss anything that is not Augustinian in perspective for nearly 1,600 years. Augustine, himself, opposed both “Pelagianism” as described by Coelestius, a disciple of Pelagius, and “Semi-Pelagianism” as the same thing. As a result, any position that might be, in any way, identified with Pelagius has been summarily dismissed and its adherents subjected to ad hominem attacks in much of Western Christianity ever since. I believe this to be a great wrong against God and His people.

I do not agree with all of the beliefs of Coelestius, as described by Augustine, but I do agree with the Semi-Pelagian position, as stated by the Baptists now and many other Christians through the ages. Here is a link to a great website that I’ve just discovered addressing some of the Pelagian issues: http://www.libraryoftheology.com/pelagianismwritings.html I wish that I had found this site when first researching this article!

If you’ve read this far, I salute your perseverance. We “Semi-Pelagians” believe in the free will of the believer and commend you for exercising yours.

Hallelujah!

As I read the surviving works of the early church fathers, I am struck at the wide variety of views provided on the subjects of sin and salvation. At this point, two thousand years removed from the church’s founding, it is easy to assume that whatever is said of a Sunday in church must be so. After all, if it was wrong someone would have fixed it by now, right? However, these issues are, in fact, not as settled as one might think.

There is, I believe, a growing restlessness within the nominally Christian culture of the West and a consequent challenge to the status quo in churches. People of good character, earnestly seeking truth, read the Nicene Creed, Augustine’s works, or simply the “statements of faith” at their local church and come to the conclusion that their God is an irrational brute condemning them to Hell for simply having been born. If the church won’t face up to the irrational aspects of their traditions, they will lose these people. That would be a tragedy for all concerned. Lost people really do need Jesus as their Savior and the church needs to present the faith in a compelling and rational manner. “God is not a God of disorder” people often say. If this is so, and I believe it is so, then a pre-Augustinian theology would seem to be in order.

While I have noted some things that I think are problematic in Augustine’s work, I cannot point to much criticism of Pelagias’ work since most of it was destroyed as a result of him being declared a heretic. Nonetheless, reading what Clement, Origen and others who preceded him had to say it becomes clear that the position reportedly held by him was more in keeping with the early church beliefs than was Augustine’s invention of Original Sin.

Clive Owen’s character, Arthur, may not have actually learned from Pelagius, but I am grateful to him for reminding me of this early church pioneer.

Thomas A. Hall

Addendum:

A week or so after having first published this article, my father, who was concerned enough about what I stated as my position to quiz me about it, sent me an email noting a recent controversy in Southern Baptist circles (He is a deacon in a Southern Baptist Church). That controversy resulted from a “Statement of Belief” authored by several prominent leaders of the Southern Baptist Convention and may be found at this link: http://theaquilareport.com/non-calvinist-southern-baptists-issue-statement-of-beliefs-by-staff/

If the reader does follow this link, they will find that the “Statement of Belief” is explicitly rejecting Calvinism—or Augustinianism, if you will.

As it turns out, and I had no idea of it when I started this investigation, the Southern Baptist view has been generally that of a “Semi-Pelagian” nature for quite some time. Having read the “Statement of Belief” and also having read an excellent discussion of it at this site: http://whytheology.wordpress.com/tag/baptist-faith-and-message/ , I find that my hard work of discovery was merely to define a theology that has been a major theme of Baptist thought for centuries. Oh well, however one gets there, it is good to get to an understanding of these matters!

It appears that my article describes, more or less, a “Semi-Pelagian” point of view. This term, “Semi-Pelagian” has been used to dismiss anything that is not Augustinian in perspective for nearly 1,600 years. Augustine, himself, opposed both “Pelagianism” as described by Coelestius, a disciple of Pelagius, and “Semi-Pelagianism” as the same thing. As a result, any position that might be, in any way, identified with Pelagius has been summarily dismissed and its adherents subjected to ad hominem attacks in much of Western Christianity ever since. I believe this to be a great wrong against God and His people.

I do not agree with all of the beliefs of Coelestius, as described by Augustine, but I do agree with the Semi-Pelagian position, as stated by the Baptists now and many other Christians through the ages. Here is a link to a great website that I’ve just discovered addressing some of the Pelagian issues: http://www.libraryoftheology.com/pelagianismwritings.html I wish that I had found this site when first researching this article!

If you’ve read this far, I salute your perseverance. We “Semi-Pelagians” believe in the free will of the believer and commend you for exercising yours.

|

|

|