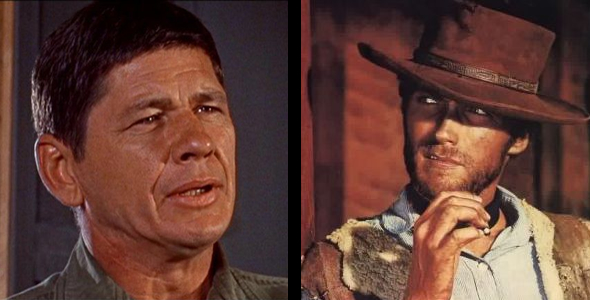

Charlie and Clint: Dead & Deader

Men are men, but some men are more man than others. We all know this, although we try to pretend otherwise. We celebrate heroes, and sometimes villains who carve their place out of the hard life that is their unfortunate lot. We especially admire those men who stare down the enemy with an iron-fisted resolve, asking no quarter and giving none in return. Men who don’t pick fights, but are more than cable of finishing them. This is never truer than when the odds move against them and they’re forced to play a hand that no man wants to be dealt.

I’m sure that such men exist, but I’ve never met one, although I have seen a few of these traits rise up, even in the meekest of men. I have, however, seen their like on the big screen. Oddly enough, even that is rarer than one might think.

The original tough guy archetype has become increasingly rare as the demand for violence has upped the ante on heroism. “If you can’t kill at least a hundred men what good are you?” has become the preferred modus operandi of a generation raised on video games. This has been the “action hero” since Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone created cartoon characters with an endless supply of quips and bullets. Films like “High Noon” or “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” by comparison, seem sedate. Why write dialogue when you can have a script that says “…and then he pulls out a Gatling gun and kills fifty men while dodging a hail of machine gun fire by as many bad guys!”? Apparently, logic doesn’t carry much weight, especially when it can be resolved by writing a scene that is limited only by the writer’s imagination.

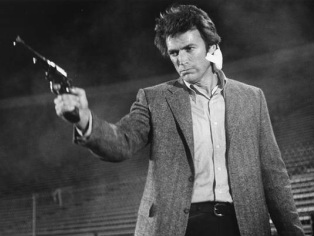

It is my arcane belief that the closer you get to the truth, the more compelling the story and action. Give the hero a genuine motive and a back story worth telling and you have the kind of stuff that drives the plot to another level. That was the difference between the original “Die Hard” and its many sequels—and Steven Spielberg’s masterpiece “Jaws” and all of the other killer animal movies that followed. It was also true of “Death Wish” which wasn't really an action film, but was a two-fisted commentary on the dissolution of American life in the 1970’s. That was the backdrop that gave the film its weight. It was likewise true for another film of the same era “Dirty Harry,” which predated ‘Death Wish” by a few years. Pauline Kael, the legendary critic for the New Yorker Magazine called it a “Fascist Masterpiece”and she was right, even if she meant it as a back-handed compliment. It was a response to the growing belief that justice was on the wane, reinforced by soaring crime statistics and ever-expanding laws designed to protect the guilty, not the innocent. If that isn't completely accurate, it was close enough for Americans worn down by war and social conflict on just about every front.

I’m sure that such men exist, but I’ve never met one, although I have seen a few of these traits rise up, even in the meekest of men. I have, however, seen their like on the big screen. Oddly enough, even that is rarer than one might think.

The original tough guy archetype has become increasingly rare as the demand for violence has upped the ante on heroism. “If you can’t kill at least a hundred men what good are you?” has become the preferred modus operandi of a generation raised on video games. This has been the “action hero” since Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone created cartoon characters with an endless supply of quips and bullets. Films like “High Noon” or “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” by comparison, seem sedate. Why write dialogue when you can have a script that says “…and then he pulls out a Gatling gun and kills fifty men while dodging a hail of machine gun fire by as many bad guys!”? Apparently, logic doesn’t carry much weight, especially when it can be resolved by writing a scene that is limited only by the writer’s imagination.

It is my arcane belief that the closer you get to the truth, the more compelling the story and action. Give the hero a genuine motive and a back story worth telling and you have the kind of stuff that drives the plot to another level. That was the difference between the original “Die Hard” and its many sequels—and Steven Spielberg’s masterpiece “Jaws” and all of the other killer animal movies that followed. It was also true of “Death Wish” which wasn't really an action film, but was a two-fisted commentary on the dissolution of American life in the 1970’s. That was the backdrop that gave the film its weight. It was likewise true for another film of the same era “Dirty Harry,” which predated ‘Death Wish” by a few years. Pauline Kael, the legendary critic for the New Yorker Magazine called it a “Fascist Masterpiece”and she was right, even if she meant it as a back-handed compliment. It was a response to the growing belief that justice was on the wane, reinforced by soaring crime statistics and ever-expanding laws designed to protect the guilty, not the innocent. If that isn't completely accurate, it was close enough for Americans worn down by war and social conflict on just about every front.

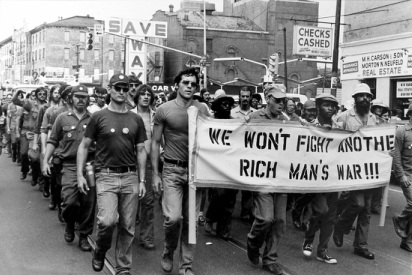

In the late 1960s and '70s, America was at war both internally and externally. Father was pitted against son, with families separated by a generation gap, a term coined to express the division between the WWII generation and their no good, draft dodging children—at least that was the older generation’s view of the younger. As a member of that no good generation I remember arguing with my father, if we were so rotten, where did we learn it from? Was it some biological predisposition towards anarchy? Or is this what happens when people get enough power and education to ask questions,”You want me to go where, and kill who”?

American films increasingly began to reflect the culture and what they reflected wasn’t pretty. Hollywood tried to keep it under wraps. But you can only keep that kind of anger quiet for so long. It was the end of the old Hollywood, the big budget musicals and Epics of the 1950’s, Technicolor, Cinemascope marvels were replaced by sepia-toned European cinema with hand held cameras, tight shots of naturally lit faces and amateur actors rounding out a cast of dozens, not thousands. Cecil B. DeMille was dead and so was traditional movie making.

The gritty, small-time filmmakers who began their careers in the 1950s like Don Siegel, the director of "Dirty Harry," were perfect for this new approach. Films shot quickly, with little artifice and a documentary-style look, pulp novel urgency, updated for a generation facing the draft and a potentially one-way ticket to Vietnam. This was especially meaningful when the enemy was the broadly defined “Red Menace,” an ominous term used to identify godless communism. Interestingly enough, capitalism was deftly putting God to death at about the same time.

American films increasingly began to reflect the culture and what they reflected wasn’t pretty. Hollywood tried to keep it under wraps. But you can only keep that kind of anger quiet for so long. It was the end of the old Hollywood, the big budget musicals and Epics of the 1950’s, Technicolor, Cinemascope marvels were replaced by sepia-toned European cinema with hand held cameras, tight shots of naturally lit faces and amateur actors rounding out a cast of dozens, not thousands. Cecil B. DeMille was dead and so was traditional movie making.

The gritty, small-time filmmakers who began their careers in the 1950s like Don Siegel, the director of "Dirty Harry," were perfect for this new approach. Films shot quickly, with little artifice and a documentary-style look, pulp novel urgency, updated for a generation facing the draft and a potentially one-way ticket to Vietnam. This was especially meaningful when the enemy was the broadly defined “Red Menace,” an ominous term used to identify godless communism. Interestingly enough, capitalism was deftly putting God to death at about the same time.

Two of the greatest films of the period “Dirty Harry” and “Death Wish” tapped into that anger in a way that transcended generational bias—anger about failed government, the breakdown of the way of life that seemed only a decade before like utopia fulfilled, but now, seemed broken beyond repair.

With fifty thousand Americans killed in Vietnam and millions more maimed showing up nightly on the television, thousands marching in the streets, African Americans burning cities in protest, women burning their bras, political assassinations, a president resigning in disgrace and much of his inner circle moving from the White House to the “Big House,” it was an anarchist's fantasy writ large.

Harry Callahan was the cop every law abiding American wanted as a guarantor against the bedlam, at least in the pinch. If he crossed the line (and sometimes completely obliterated it) that was okay, as long as that line had previously been clearly defined. This appeared oxymoronic, but was intuited as correct deep in the recesses of the factory towns and on Mainstreet where hard working people expected safe streets and reasonably honest politicians.

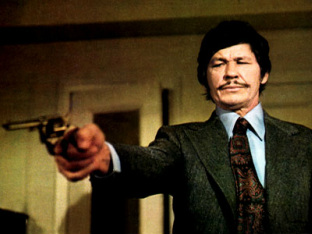

In Death Wish, Bronson’s Paul Kersey was the model of the successful urban professional whose wealth had failed to insulate him from the rabble. When the rich can’t find refuge, either revolution is at hand or the system has completely broken down. Both were active agents in American life in the 1960s and '70s. The American middle class watched incredulously as their children gleefully took a hatchet to the country's foundation. For the wealthy, it was the Barbarians at the gate, Rome’s last gasp before the Hun pulled down the Senate.

Both Clint Eastwood and Charles Bronson were transitional figures between John Wayne and Stallone and Schwarzenegger, emerging at a time when television had substantially diminished the economic clout of the film business. The movie palaces that were on nearly every corner began shutting their doors and were replaced by television. Audiences, looking for new thrills, eventually found violence and nudity suitable substitutes for biblical epics and big budget musicals. The end of the “Production Code” that had governed movies since 1934 was done away with in 1968 and, in a few short years, violence and sex permeated the cinematic experience. I can remember seeing “Deep Throat” in a mainstream theater in 1973 with a packed audience, and believe me, it wasn't the raincoat crowd that filled the theater, but respectable husbands and wives. At least they gave the appearance of respectability in the dark.

Eastwood and Bronson were dominant figures at the box office in the 1970’s and at one point Charles Bronson, the least likely leading man, possibly in the history of film up to that point, became the biggest star in the world. Both made a number of films that maintain their power forty years later. In fact, some of their best work seems more like European-produced Art House cinema, than anything made today—minus the substantial body count, of course.

With fifty thousand Americans killed in Vietnam and millions more maimed showing up nightly on the television, thousands marching in the streets, African Americans burning cities in protest, women burning their bras, political assassinations, a president resigning in disgrace and much of his inner circle moving from the White House to the “Big House,” it was an anarchist's fantasy writ large.

Harry Callahan was the cop every law abiding American wanted as a guarantor against the bedlam, at least in the pinch. If he crossed the line (and sometimes completely obliterated it) that was okay, as long as that line had previously been clearly defined. This appeared oxymoronic, but was intuited as correct deep in the recesses of the factory towns and on Mainstreet where hard working people expected safe streets and reasonably honest politicians.

In Death Wish, Bronson’s Paul Kersey was the model of the successful urban professional whose wealth had failed to insulate him from the rabble. When the rich can’t find refuge, either revolution is at hand or the system has completely broken down. Both were active agents in American life in the 1960s and '70s. The American middle class watched incredulously as their children gleefully took a hatchet to the country's foundation. For the wealthy, it was the Barbarians at the gate, Rome’s last gasp before the Hun pulled down the Senate.

Both Clint Eastwood and Charles Bronson were transitional figures between John Wayne and Stallone and Schwarzenegger, emerging at a time when television had substantially diminished the economic clout of the film business. The movie palaces that were on nearly every corner began shutting their doors and were replaced by television. Audiences, looking for new thrills, eventually found violence and nudity suitable substitutes for biblical epics and big budget musicals. The end of the “Production Code” that had governed movies since 1934 was done away with in 1968 and, in a few short years, violence and sex permeated the cinematic experience. I can remember seeing “Deep Throat” in a mainstream theater in 1973 with a packed audience, and believe me, it wasn't the raincoat crowd that filled the theater, but respectable husbands and wives. At least they gave the appearance of respectability in the dark.

Eastwood and Bronson were dominant figures at the box office in the 1970’s and at one point Charles Bronson, the least likely leading man, possibly in the history of film up to that point, became the biggest star in the world. Both made a number of films that maintain their power forty years later. In fact, some of their best work seems more like European-produced Art House cinema, than anything made today—minus the substantial body count, of course.

Bronson’s “Hard Times” is, according to many critics and fight aficionados alike, the greatest fight film ever made—a masterful slice of life character study of the male myth told with few words and relatively modest, but beautifully directed action sequences. Bronson completely embodies the role with a lithe, athletic physicality and a spare acting style, playing a variation on the lone gunfighter, only it’s his fists that are the weapon of choice. Combined with a face that looked like it was carved from stone, better suited to horror movies than leading men, Bronson made the story believable in a way I’m not sure any other actor could. It also has James Coburn in one of the finest performances of his career as the apex smart-ass who lives at the cross section where the low-life and the swells intersect. Another of the constants of 1960s and '70s cinema rounding out the cast is the consummate character actor, Strother Martin. A few of the films that Martin appeared in "Cool Hand Luke," "True Grit," "The Wild Bunch," "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid," were among the best films of the era. He elevated even marginal roles with an often seething, understated menace, tinged with a comedic element, imbuing his parts, no matter how small, with far more detail than was written on the page.

Some critics have suggested that Bronson in "Hard Times" is the every-man; dock worker, blue collar laborer, field hand, whatever, making it a kind of socialists homage to the hard scrabble existence that molds hard men for hard times. Where there may be a hint of truth in the idea, the film is really about the beauty of "genius". Bronson's character, "Chaney," is a rare and true artist working in the most primal of mediums. He is what every man, despite their pleas to the contrary, wants to be. He is the lone figure, self-reliant, with a moral base, who is indifferent to other peoples' perception of him. He needs no external source to elevate his worth, and when everything else is stripped away, he is the best of the best at what Darwin tells us is man's purpose, a survivor, the last man standing who can do what needs to be done and then quietly wipe off the sweat and walk away.

The worth of the film isn't found in its dialogue, which works at a reasonably high level. But the decision to let the story and the perfectly-cast ensemble of actors embody their characters while the camera tracks their movement, allowing the shot to capture the action and the environment that is it's strength. It is the sum of its various parts that makes it a great movie.

In the late 1960’s the anti-hero replaced the hero as the central figure in movies, one that first emerged in the work of Marlon Brando in the 1950’s, before James Dean, Elvis or rock and roll. By the late 1960’s what had been the anomaly for leading men became the norm—the outsider, the man on the margins, motivated by complex internal drives, neither good or bad was the center of a growing moral ambiguity in film.

Clint Eastwood’s “High Plains Drifter” rewrote Fred Zinnemann’s classic western “High Noon” reinterpreting the political elements in the film, upending the western myth as a nihilistic revenge epic. Like its predecessor, it was hated by John Wayne, who saw the film as rewriting American history. It was a dark, violent, iconoclastic film that had no heroes, at least none in the archetypal mold of Hollywood’s heyday.

Charles Bronson’s film “The Mechanic” had a Mafia hit-man as a lead. Not a misguided thug who finds out he has a heart of gold and is somehow redeemed, or a raging sociopath, but a man who views professional murder as a meaningful form of intellectual self-expression.

By the 1980’s both Eastwood and Bronson’s career had begun to stall. Eastwood continued to make some decent films, but increasingly moved to directing. Bronson made a number of mediocre and sub-par films, including numerous “Death Wish" sequels. But the real downfall came when Steven Spielberg’s film "Jaws" broke all records and George Lucas revived the Saturday afternoon serialized matinee as a big budget, effects heavy, Cowboys and Indians in outer space epic with “Star Wars.” Audiences once again bought tickets in huge numbers and made the big budget action film with clear-cut good guys and bad guys highly profitable. Sylvester Stallone drove the final nail in the coffin with “Rocky.”

Even after the reemergence of the summer blockbuster, the big movie palaces never returned, they were replaced by Cineplex’s, with smaller screens, inflated ticket prices and cramped seating. It is likely, now, that even these will begin to disappear as home theaters become cheaper and the internet finally gives everything away for free, or something close to it.

The movies, however, will never really go away. They will change as technology changes. Budding filmmakers with affordable cameras and computer technology will reinvent the form yet again. Big pictures will still be made, although, probably, less often. Small films will inundate the various emerging venues, the new guard will replace the old, plenty of rotten films will hit the market, idiots will be hailed as geniuses, but there will, no doubt, be some authentic ones as well. The cartoon facsimiles will eventually give way to a grittier reality and the "real man" will have his day once again. Until then, Charlie and Clint will do just fine.

Mark Magula

Some critics have suggested that Bronson in "Hard Times" is the every-man; dock worker, blue collar laborer, field hand, whatever, making it a kind of socialists homage to the hard scrabble existence that molds hard men for hard times. Where there may be a hint of truth in the idea, the film is really about the beauty of "genius". Bronson's character, "Chaney," is a rare and true artist working in the most primal of mediums. He is what every man, despite their pleas to the contrary, wants to be. He is the lone figure, self-reliant, with a moral base, who is indifferent to other peoples' perception of him. He needs no external source to elevate his worth, and when everything else is stripped away, he is the best of the best at what Darwin tells us is man's purpose, a survivor, the last man standing who can do what needs to be done and then quietly wipe off the sweat and walk away.

The worth of the film isn't found in its dialogue, which works at a reasonably high level. But the decision to let the story and the perfectly-cast ensemble of actors embody their characters while the camera tracks their movement, allowing the shot to capture the action and the environment that is it's strength. It is the sum of its various parts that makes it a great movie.

In the late 1960’s the anti-hero replaced the hero as the central figure in movies, one that first emerged in the work of Marlon Brando in the 1950’s, before James Dean, Elvis or rock and roll. By the late 1960’s what had been the anomaly for leading men became the norm—the outsider, the man on the margins, motivated by complex internal drives, neither good or bad was the center of a growing moral ambiguity in film.

Clint Eastwood’s “High Plains Drifter” rewrote Fred Zinnemann’s classic western “High Noon” reinterpreting the political elements in the film, upending the western myth as a nihilistic revenge epic. Like its predecessor, it was hated by John Wayne, who saw the film as rewriting American history. It was a dark, violent, iconoclastic film that had no heroes, at least none in the archetypal mold of Hollywood’s heyday.

Charles Bronson’s film “The Mechanic” had a Mafia hit-man as a lead. Not a misguided thug who finds out he has a heart of gold and is somehow redeemed, or a raging sociopath, but a man who views professional murder as a meaningful form of intellectual self-expression.

By the 1980’s both Eastwood and Bronson’s career had begun to stall. Eastwood continued to make some decent films, but increasingly moved to directing. Bronson made a number of mediocre and sub-par films, including numerous “Death Wish" sequels. But the real downfall came when Steven Spielberg’s film "Jaws" broke all records and George Lucas revived the Saturday afternoon serialized matinee as a big budget, effects heavy, Cowboys and Indians in outer space epic with “Star Wars.” Audiences once again bought tickets in huge numbers and made the big budget action film with clear-cut good guys and bad guys highly profitable. Sylvester Stallone drove the final nail in the coffin with “Rocky.”

Even after the reemergence of the summer blockbuster, the big movie palaces never returned, they were replaced by Cineplex’s, with smaller screens, inflated ticket prices and cramped seating. It is likely, now, that even these will begin to disappear as home theaters become cheaper and the internet finally gives everything away for free, or something close to it.

The movies, however, will never really go away. They will change as technology changes. Budding filmmakers with affordable cameras and computer technology will reinvent the form yet again. Big pictures will still be made, although, probably, less often. Small films will inundate the various emerging venues, the new guard will replace the old, plenty of rotten films will hit the market, idiots will be hailed as geniuses, but there will, no doubt, be some authentic ones as well. The cartoon facsimiles will eventually give way to a grittier reality and the "real man" will have his day once again. Until then, Charlie and Clint will do just fine.

Mark Magula

|

|

|