The Original Guitar Heroes + One

Part I - The Original Guitar Heroes + 1

Of the four musicians featured in the video below, Tom Jones, Jerry Reed, Glen Campbell and Big Jim Sullivan, three were among the most sought after session musicians of the 1960’s. Before Glen Campbell's success as a solo performer, he had been a member of the Wrecking Crew—a name given to a small but select group of studio players who appeared on almost every major record that came out of the L.A. recording scene. Artists like Frank Sinatra, the Beach Boys (of which he was a recording and touring member, including Pet Sounds), The Mama’s and the Papa’s, Phil Specter, the Monkees, and innumerable others.

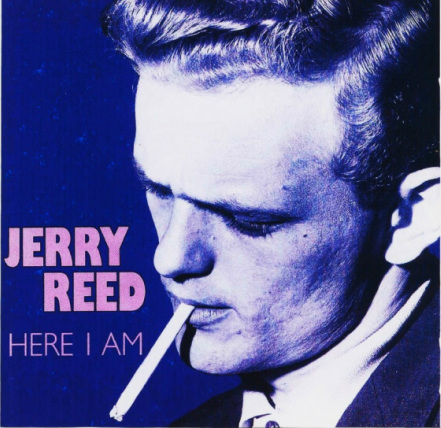

Jerry Reed came into national prominence as a frequent guest on Glen Campbell’s popular weekly television show. However, it was through a series of solo recordings and session work dating back to the early days of rock and roll that he first developed his reputation. Reed quickly became known as a fine songwriter and one of the most gifted and original guitarists in Nashville, a city overrun by great players.

What Campbell and Reed were to L.A. and Nashville, Big Jim Sullivan was to the Beatles-era British pop scene—eventually becoming a regularly-featured part of Tom Jones’ highly successful television show.

At a time in the sixties when innovative young players like Clapton, Beck and Hendrix were redefining the sound of the instrument, it was Campbell, Reed and Sullivan who were the original guitar heroes. Television gave them a unique platform to display their skills, providing a common link between an older generation and the rapidly emerging future.

Tom Jones, the lone non-guitarist of the group had his first hit nearly a half century ago, while a recent performance for PBS with only guitar accompaniment gives ample evidence of his remarkable and enduring gifts. Jones, like the other performers in this video, was of a slightly older generation than most of their contemporaries of the 1960’s. He, and they, straddled the fence between generations as well as genres.

What is most compelling about this video is the obvious fun being had by everyone involved. Jerry’s opening playing is nothing less than a workshop on how to accompany a singer with chords and arpeggios. He follows this with an equally stunning solo chorus followed by more inventive accompaniment. Glen sings and takes a chorus and then Tom Jones shows why he is considered a legend, even by those too young to remember him in his early years.

Like so much of the best 20th Century American music, it's an offering of blues, soul, jazz and country. Not surprisingly, it was made by British and American musicians who couldn’t care less about boundaries, and had only two things in mind, making good music and enjoying the hell out of it.

Jerry Reed came into national prominence as a frequent guest on Glen Campbell’s popular weekly television show. However, it was through a series of solo recordings and session work dating back to the early days of rock and roll that he first developed his reputation. Reed quickly became known as a fine songwriter and one of the most gifted and original guitarists in Nashville, a city overrun by great players.

What Campbell and Reed were to L.A. and Nashville, Big Jim Sullivan was to the Beatles-era British pop scene—eventually becoming a regularly-featured part of Tom Jones’ highly successful television show.

At a time in the sixties when innovative young players like Clapton, Beck and Hendrix were redefining the sound of the instrument, it was Campbell, Reed and Sullivan who were the original guitar heroes. Television gave them a unique platform to display their skills, providing a common link between an older generation and the rapidly emerging future.

Tom Jones, the lone non-guitarist of the group had his first hit nearly a half century ago, while a recent performance for PBS with only guitar accompaniment gives ample evidence of his remarkable and enduring gifts. Jones, like the other performers in this video, was of a slightly older generation than most of their contemporaries of the 1960’s. He, and they, straddled the fence between generations as well as genres.

What is most compelling about this video is the obvious fun being had by everyone involved. Jerry’s opening playing is nothing less than a workshop on how to accompany a singer with chords and arpeggios. He follows this with an equally stunning solo chorus followed by more inventive accompaniment. Glen sings and takes a chorus and then Tom Jones shows why he is considered a legend, even by those too young to remember him in his early years.

Like so much of the best 20th Century American music, it's an offering of blues, soul, jazz and country. Not surprisingly, it was made by British and American musicians who couldn’t care less about boundaries, and had only two things in mind, making good music and enjoying the hell out of it.

Part II - Guitar Man - the song

Jerry’s unique fingerpicked guitar style, as well as his exceptional gifts as a songwriter, can be heard everywhere on the second video below. You get the sense in listening to his music that he took in everything that he crossed paths with. He was prolific as a composer, having written a number of songs for Chet Atkins among others, including a number of hits of his own that crossed over to both the pop and country charts.

You might expect that a gifted instrumentalist should have a grasp of song writing fundamentals, although that’s not always the case. In fact, virtuosity can be as much a stumbling block to the aspiring songwriter as an asset. Many gifted players find it hard to keep it simple or at least to find a way to utilize their abundant technical prowess in the service of a song. And a gift for a clever riff doesn’t mean that you can write words.

Writing lyrics is different than writing prose or poetry. The images have to fit the rhythm of the music and tell a complete story in the span of a three-minute song. Very few songwriters ever get that blend right. Too much poetry and you lose the story, too little poetry and you end up with bad journalism put to music. Bob Dylan wrote stream of consciousness lyrics, but never lost sight of the need for his words to groove. If you want a lesson in lyric writing, Dylan isn’t a bad start. Lennon and McCartney or Cole Porter, Ira Gershwin or Hank Williams are all models for the budding lyricist. There is, however, one towering giant among melodious wordsmiths whose output stands as perhaps the greatest body of euphonious verbiage ever put on a 45 RPM disc. A man of towering gifts as a guitarist, one who could sling a reconstituted Elmore James riff like no one else—the original Guitar-Man himself, The Maestro, Chuck Berry! Mr. Berry had a talent for narrative, with a novelist's feel for character and an ad-man’s flair for how best to condense them into a short, complete two-and-a-half-minute anthem—it was syncopated confabulation of the highest order.

It’s clear that Jerry Reed learned a few things from Mr. Berry; he was after all a contemporary, not a later pretender to the rock and roll throne. Both were brilliant guitarists and songwriters. Reed’s fingerpicked; banjo-like finger-rolls, odd tunings and arpeggios were equal parts blues, country, gospel, rhythm & blues and jazz, they were the product of an agile mind and equally agile and inventive guitar technique.

Reed’s song Guitar-Man, is a good example of his unorthodox approach as both a writer and guitarist—he takes a blues progression, lays it on top of a mutated bossa-nova rhythm, adds in a slice-of-life story that’s so vivid it could be a movie. Elvis took it and made it his own after hearing Reed’s version—requesting that Jerry come and play on the session and bring a little of his distinctive guitar magic with him. The rest, of course, is history. The song has been recorded many times and by many people, but I would suggest the performance in the video below is my favorite. Three artists at their peak, letting it all hang out. As Stan-the man Lee used to say—nuff said!

Mark Magula

You might expect that a gifted instrumentalist should have a grasp of song writing fundamentals, although that’s not always the case. In fact, virtuosity can be as much a stumbling block to the aspiring songwriter as an asset. Many gifted players find it hard to keep it simple or at least to find a way to utilize their abundant technical prowess in the service of a song. And a gift for a clever riff doesn’t mean that you can write words.

Writing lyrics is different than writing prose or poetry. The images have to fit the rhythm of the music and tell a complete story in the span of a three-minute song. Very few songwriters ever get that blend right. Too much poetry and you lose the story, too little poetry and you end up with bad journalism put to music. Bob Dylan wrote stream of consciousness lyrics, but never lost sight of the need for his words to groove. If you want a lesson in lyric writing, Dylan isn’t a bad start. Lennon and McCartney or Cole Porter, Ira Gershwin or Hank Williams are all models for the budding lyricist. There is, however, one towering giant among melodious wordsmiths whose output stands as perhaps the greatest body of euphonious verbiage ever put on a 45 RPM disc. A man of towering gifts as a guitarist, one who could sling a reconstituted Elmore James riff like no one else—the original Guitar-Man himself, The Maestro, Chuck Berry! Mr. Berry had a talent for narrative, with a novelist's feel for character and an ad-man’s flair for how best to condense them into a short, complete two-and-a-half-minute anthem—it was syncopated confabulation of the highest order.

It’s clear that Jerry Reed learned a few things from Mr. Berry; he was after all a contemporary, not a later pretender to the rock and roll throne. Both were brilliant guitarists and songwriters. Reed’s fingerpicked; banjo-like finger-rolls, odd tunings and arpeggios were equal parts blues, country, gospel, rhythm & blues and jazz, they were the product of an agile mind and equally agile and inventive guitar technique.

Reed’s song Guitar-Man, is a good example of his unorthodox approach as both a writer and guitarist—he takes a blues progression, lays it on top of a mutated bossa-nova rhythm, adds in a slice-of-life story that’s so vivid it could be a movie. Elvis took it and made it his own after hearing Reed’s version—requesting that Jerry come and play on the session and bring a little of his distinctive guitar magic with him. The rest, of course, is history. The song has been recorded many times and by many people, but I would suggest the performance in the video below is my favorite. Three artists at their peak, letting it all hang out. As Stan-the man Lee used to say—nuff said!

Mark Magula

|

|

|

|

|

|