The Box of Teeth

Death is a friend to few, an unwelcome stranger to most. There are times, often when we are young, that we tempt fate willingly, less as the result of bravery and more the result of ignorance. If we’re fortunate we survive our youthful indiscretions and live a long life. Others are not so lucky. They come face to face with death in one of its many disguises as a matter of circumstance, finding themselves at the wrong place and the wrong time—hell’s lottery played out with all the right numbers, only there are no winners.

Once, when I was nineteen and eager for a vacation from reality, I went out to the local cow pasture with my best friend to pick some “Magic Mushrooms”. Our intent was to boil them down for the psilocybin, a naturally occurring psychedelic compound, mix it with some Kool-Aid to make it less bitter and get a free high. Being inexperienced we drank more than we should have, and within minutes we began our procession down the rabbit’s-hole with little or no idea of what was waiting at the other end. It was the journey we were after—new life experiences—and within a few hours, after the melting clocks and the clouds had subsided, we found ourselves in my truck, sitting in the middle of the highway with the traffic coming directly at us. We were frozen in place, a few short moments from an untimely and very unnecessary end. Thankfully, my friend mustered the necessary cognitive facility to push me over and take the wheel.

But Death inevitably comes for everyone, although it's seldom ever as thoughtlessly invited as that night on the highway. Most of us work diligently to keep it a distance, hoping that it passes by in pursuit of a better candidate.

Just how many times its brushed past with me unaware would be anyone’s guess. We've all had those moments as a kid when we ran in front of a car and just barely avoided contact. The time we slipped and began the descent down from some high place we should have never been to begin with. Frequently it’s our own obsessions that draw us to the ledge. But sometimes, we find ourselves at the intersection of someone, or something’s obsession, like a man stranded at sea with a fin coming into view—and then, what we want, matters a good deal less.

Some forty years ago in South Florida there was a male hitchhiker that would jump into woman’s cars and rape and strangle them. He would stand by the road at night, thumbing a ride, on the hunt for his type—young women with long straight hair who were driving alone with their doors unlocked, making them an easy target for a killer. My girlfriend fit the description almost perfectly and tended to drive home on the strip that had become his preferred hunting grounds. I would tell her “Lock your door”! She would laugh and drive off, indifferent to the possibility that she could be a victim, others maybe, but not her. That night as she drove home she saw a man thumbing a ride. Just as she was about to pass by he lunged at her door and attempted to jump in—but not before she hit the gas pedal and got the hell out of there. Unlike those unfortunate others, she survived her encounter, and four years later become my wife. The killer, whoever he may have been, was never caught.

These are the obvious moments when we can see the enemy close enough to make out a face, its amorphous features more clearly defined. But there are almost certainly moments when death is downwind, and we never know just how close it came.

In the summer of 1966 I found myself on a train with my mother and sister, on route to visit family in Mississippi. We had a two hour layover in Chicago, the biggest city I’d ever seen. It was the archetype of the great metropolis with giant skyscrapers, massive billboards advertising

every kind of product. And, at the other end were rows of multi-story, wood frame tenement houses that could be viewed as our train made its way to the station. These were urban slums the likes of which I had seen only in the movies. Separated by an invisible demarcation line that isolated the public squalor from the gleaming city

We had made this trip before and Chicago was always the high point of the journey. This time, however, it was different. The previous night a man had murdered eight nurses in Chicago, in one of the worse spree killings of the 20th century. We were only passing through, stuck on a two hour layover, but just the thought that this monster could be waiting for a train like we were created a sense of dread that never left until we were safely back on the train and almost in Mississippi.

Even when the monster was caught and given a name “Richard Speck” the face was unrecognizable as human. Not because he looked so different. His face was just another image peering out of a photograph, eyes and features like other men, but, apparently, not at all like other men.

Once, when I was nineteen and eager for a vacation from reality, I went out to the local cow pasture with my best friend to pick some “Magic Mushrooms”. Our intent was to boil them down for the psilocybin, a naturally occurring psychedelic compound, mix it with some Kool-Aid to make it less bitter and get a free high. Being inexperienced we drank more than we should have, and within minutes we began our procession down the rabbit’s-hole with little or no idea of what was waiting at the other end. It was the journey we were after—new life experiences—and within a few hours, after the melting clocks and the clouds had subsided, we found ourselves in my truck, sitting in the middle of the highway with the traffic coming directly at us. We were frozen in place, a few short moments from an untimely and very unnecessary end. Thankfully, my friend mustered the necessary cognitive facility to push me over and take the wheel.

But Death inevitably comes for everyone, although it's seldom ever as thoughtlessly invited as that night on the highway. Most of us work diligently to keep it a distance, hoping that it passes by in pursuit of a better candidate.

Just how many times its brushed past with me unaware would be anyone’s guess. We've all had those moments as a kid when we ran in front of a car and just barely avoided contact. The time we slipped and began the descent down from some high place we should have never been to begin with. Frequently it’s our own obsessions that draw us to the ledge. But sometimes, we find ourselves at the intersection of someone, or something’s obsession, like a man stranded at sea with a fin coming into view—and then, what we want, matters a good deal less.

Some forty years ago in South Florida there was a male hitchhiker that would jump into woman’s cars and rape and strangle them. He would stand by the road at night, thumbing a ride, on the hunt for his type—young women with long straight hair who were driving alone with their doors unlocked, making them an easy target for a killer. My girlfriend fit the description almost perfectly and tended to drive home on the strip that had become his preferred hunting grounds. I would tell her “Lock your door”! She would laugh and drive off, indifferent to the possibility that she could be a victim, others maybe, but not her. That night as she drove home she saw a man thumbing a ride. Just as she was about to pass by he lunged at her door and attempted to jump in—but not before she hit the gas pedal and got the hell out of there. Unlike those unfortunate others, she survived her encounter, and four years later become my wife. The killer, whoever he may have been, was never caught.

These are the obvious moments when we can see the enemy close enough to make out a face, its amorphous features more clearly defined. But there are almost certainly moments when death is downwind, and we never know just how close it came.

In the summer of 1966 I found myself on a train with my mother and sister, on route to visit family in Mississippi. We had a two hour layover in Chicago, the biggest city I’d ever seen. It was the archetype of the great metropolis with giant skyscrapers, massive billboards advertising

every kind of product. And, at the other end were rows of multi-story, wood frame tenement houses that could be viewed as our train made its way to the station. These were urban slums the likes of which I had seen only in the movies. Separated by an invisible demarcation line that isolated the public squalor from the gleaming city

We had made this trip before and Chicago was always the high point of the journey. This time, however, it was different. The previous night a man had murdered eight nurses in Chicago, in one of the worse spree killings of the 20th century. We were only passing through, stuck on a two hour layover, but just the thought that this monster could be waiting for a train like we were created a sense of dread that never left until we were safely back on the train and almost in Mississippi.

Even when the monster was caught and given a name “Richard Speck” the face was unrecognizable as human. Not because he looked so different. His face was just another image peering out of a photograph, eyes and features like other men, but, apparently, not at all like other men.

In the 1960’s and 70’s serial murder was rare, in fact I’m not sure that the term was even in use then. The thought of a homicidal maniac living anywhere in the vicinity, even in the same state was enough to install panic in people. Television and films were, for the most part free of graphic violence. There was violence sure enough, but most of it was of the bloodless variety.

On television you could kill a dozen people with a machine gun and never see a drop of blood. Filmmakers like Sam Peckinpah changed that, but like all revolutions, good and bad, the change comes slowly, first at the fringes and only later does it filter into the mainstream.

There was, however, plenty of violence in the streets, the result of political unrest and protest. There were multiple major political assassinations, President Kennedy in 1963, his brother Robert Kennedy, the former Senator and Attorney General in 1967, Malcolm X in 1965--and Martin Luther King in 1968, to say nothing of The Vietnam War.

Television, however, offered an antidote to the harsh external reality of American life with millionaire hillbillies, magical witches, beautiful Genies, made for TV rock-bands like The Monkees and talking horses. America in the 1960's was, in many ways, a schizophrenic teenager with a deep seeded authority problem. One that could effortlessly turn a buck, with an undeniable gift for creativity.

In the summer of 1966 I found myself on a train with my mother and sister, on route to visit family in Mississippi. We had a two hour layover in Chicago, which was the biggest city I’d ever seen. It was the archetype of the great metropolis with giant skyscrapers, massive billboards advertising every kind of product. And, at the other end of the city were rows of multi-story, wood frame tenement houses that could be viewed as our train made its way to the station. These were urban slums the likes of which I had seen only in the movies. Separate from the gleaming city by an invisible demarcation line that isolated the public squalor.

We had made this trip before and Chicago was always the high point of the journey. This time, however, it was different. The previous night a man had murdered eight nurses in Chicago, in one of the worse spree killings of the 20th century. We were only passing through, stuck on a two hour layover, but just the thought that the monster could be waiting for a train like we were created a sense of dread that never left until we were safely back on the train and almost in Mississippi. Even when the monster was caught and given a name “Richard Speck” the face was unrecognizable as human. Not because he looked so different. It was just another image peering out of a photograph, eyes and features like other men, but, apparently, not at all like other men.

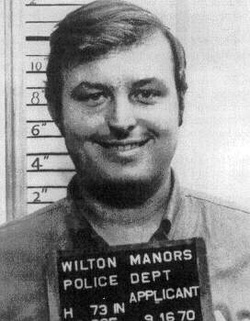

Some six summers later, on hot day in July Officer Schaefer, the cop from the neighborhood picked up a couple of attractive young female hitchhikers, Nancy Ellen Trotter and Pamela Sue Wells. He lectured them about the dangers of hitchhiking and told them, “You never knew who might be driving the car that you get into”. As a favor he offered to pick them up the next day and drive them to their destination, just a friendly cop trying to keep a couple of girls safe from potential predators. Camouflage is one nature’s great achievements. It allows a predator to move, virtually unseen, within inches of its target. Stealth enables a crocodile to remain submerged in only a few inches of water, with only its eyes exposed—its massive jaws and bulk hidden just beneath the surface. A six hundred pound Lion is essentially invisible in the high amber grass of the African Savannah as it waits for its prey. For officer Schaefer it was a badge, a friendly smile and a few words spoken with the illusion of concern. Both girls agreed to meet him the next day and take him up on his offer.

Nearly twenty four hour later they staggered into the local police station, frightened and exhausted and told their story about how office Schaffer had offered to give them a ride, but instead, drove them deep into the everglades and tied them to a tree. Their legs and hands bound, with a hangman's noose carefully tied around their necks, threatening to strangle them if they slipped and fell. Fortunately, they managed to escape and made their way to the local police station, which turned out the same one that Officer Schaefer worked at.

In 1972 there was a man named Gerard John Shaffer that lived directly behind my wife’s grandmother’s house, which was only a few blocks from my own house. In every way he was essentially nondescript. With one exception, he was a police officer. I have no idea of how often I saw him, probably often enough. He was slightly chubby, with medium brown hair worn in the fashion typical of men in the early 1970’s. Although he was in his thirties he still lived with his mother. He was tall and pleasant enough. But he was a cop, and that was reason enough to keep him at arm’s length, especially for a bunch of teenagers who occasionally pushed the boundaries of

the law. We weren’t the “James Gang” or even street thugs. It was more a case of smoking pot and playing our music too loud. That’s what you’re supposed to do in a rock and roll band, which is what we were, and if some adult gave us crap, we gave it back. Thankfully, we never had to deal

with officer Shaffer Not that he was intimidating, he wasn't but, there were plenty of reasons to be afraid. Far more than any of us knew.

On television you could kill a dozen people with a machine gun and never see a drop of blood. Filmmakers like Sam Peckinpah changed that, but like all revolutions, good and bad, the change comes slowly, first at the fringes and only later does it filter into the mainstream.

There was, however, plenty of violence in the streets, the result of political unrest and protest. There were multiple major political assassinations, President Kennedy in 1963, his brother Robert Kennedy, the former Senator and Attorney General in 1967, Malcolm X in 1965--and Martin Luther King in 1968, to say nothing of The Vietnam War.

Television, however, offered an antidote to the harsh external reality of American life with millionaire hillbillies, magical witches, beautiful Genies, made for TV rock-bands like The Monkees and talking horses. America in the 1960's was, in many ways, a schizophrenic teenager with a deep seeded authority problem. One that could effortlessly turn a buck, with an undeniable gift for creativity.

In the summer of 1966 I found myself on a train with my mother and sister, on route to visit family in Mississippi. We had a two hour layover in Chicago, which was the biggest city I’d ever seen. It was the archetype of the great metropolis with giant skyscrapers, massive billboards advertising every kind of product. And, at the other end of the city were rows of multi-story, wood frame tenement houses that could be viewed as our train made its way to the station. These were urban slums the likes of which I had seen only in the movies. Separate from the gleaming city by an invisible demarcation line that isolated the public squalor.

We had made this trip before and Chicago was always the high point of the journey. This time, however, it was different. The previous night a man had murdered eight nurses in Chicago, in one of the worse spree killings of the 20th century. We were only passing through, stuck on a two hour layover, but just the thought that the monster could be waiting for a train like we were created a sense of dread that never left until we were safely back on the train and almost in Mississippi. Even when the monster was caught and given a name “Richard Speck” the face was unrecognizable as human. Not because he looked so different. It was just another image peering out of a photograph, eyes and features like other men, but, apparently, not at all like other men.

Some six summers later, on hot day in July Officer Schaefer, the cop from the neighborhood picked up a couple of attractive young female hitchhikers, Nancy Ellen Trotter and Pamela Sue Wells. He lectured them about the dangers of hitchhiking and told them, “You never knew who might be driving the car that you get into”. As a favor he offered to pick them up the next day and drive them to their destination, just a friendly cop trying to keep a couple of girls safe from potential predators. Camouflage is one nature’s great achievements. It allows a predator to move, virtually unseen, within inches of its target. Stealth enables a crocodile to remain submerged in only a few inches of water, with only its eyes exposed—its massive jaws and bulk hidden just beneath the surface. A six hundred pound Lion is essentially invisible in the high amber grass of the African Savannah as it waits for its prey. For officer Schaefer it was a badge, a friendly smile and a few words spoken with the illusion of concern. Both girls agreed to meet him the next day and take him up on his offer.

Nearly twenty four hour later they staggered into the local police station, frightened and exhausted and told their story about how office Schaffer had offered to give them a ride, but instead, drove them deep into the everglades and tied them to a tree. Their legs and hands bound, with a hangman's noose carefully tied around their necks, threatening to strangle them if they slipped and fell. Fortunately, they managed to escape and made their way to the local police station, which turned out the same one that Officer Schaefer worked at.

In 1972 there was a man named Gerard John Shaffer that lived directly behind my wife’s grandmother’s house, which was only a few blocks from my own house. In every way he was essentially nondescript. With one exception, he was a police officer. I have no idea of how often I saw him, probably often enough. He was slightly chubby, with medium brown hair worn in the fashion typical of men in the early 1970’s. Although he was in his thirties he still lived with his mother. He was tall and pleasant enough. But he was a cop, and that was reason enough to keep him at arm’s length, especially for a bunch of teenagers who occasionally pushed the boundaries of

the law. We weren’t the “James Gang” or even street thugs. It was more a case of smoking pot and playing our music too loud. That’s what you’re supposed to do in a rock and roll band, which is what we were, and if some adult gave us crap, we gave it back. Thankfully, we never had to deal

with officer Shaffer Not that he was intimidating, he wasn't but, there were plenty of reasons to be afraid. Far more than any of us knew.