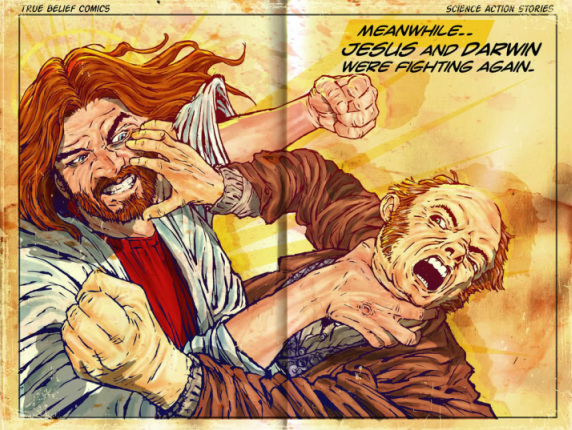

The Battle: Science vs Faith & the fate of the world

There is a new militancy in the air—specifically in American culture regarding religion. Most Americans are oblivious to the battle because it hasn't broken into their living rooms with sufficient entertainment value to displace the latest reality show. If we could just find a couple of nubile young woman and buff young men to hold the public’s attention long enough, while simultaneously reducing the complexity of the debate to a few slogans, we might get somewhere.

At the outer edges of the discussion is a bunch of angry young people, mostly males, armed with Richard Dawkin's "The God Delusion,” anxiously searching through Wikipedia in an effort to reinforce their new atheistic faith. On the other side are Evangelical fundamentalists of all ages with a personalized, self-help Gospel dogmatically asserting ideas that are the product of an ancient culture and then reinterpreted in the light of a vastly different time and place. Both sides are equally unwilling to give ground, operating with absolute certainty regarding their individual positions. At stake, as each side sees it, is the future of the universe—Heaven, Hell and the freedom of the individual from the tyranny of the majority—whoever and whatever that might be.

As with all politics and religion, the camel is always ready, its nose probing the perimeter of the tent, searching for weaknesses, careful never to give an inch, always positioned for an imminent takeover.

None of this is new, mind you. Competition drives people of similar faiths regardless of discipline, whether religious in nature or scientific—and has since the beginning of recorded history. The tendency to see our own experience as definitive seems to be drawn equally from the limitations of human perception and the enormous visionary expanses of our imaginations.

At the outer edges of the discussion is a bunch of angry young people, mostly males, armed with Richard Dawkin's "The God Delusion,” anxiously searching through Wikipedia in an effort to reinforce their new atheistic faith. On the other side are Evangelical fundamentalists of all ages with a personalized, self-help Gospel dogmatically asserting ideas that are the product of an ancient culture and then reinterpreted in the light of a vastly different time and place. Both sides are equally unwilling to give ground, operating with absolute certainty regarding their individual positions. At stake, as each side sees it, is the future of the universe—Heaven, Hell and the freedom of the individual from the tyranny of the majority—whoever and whatever that might be.

As with all politics and religion, the camel is always ready, its nose probing the perimeter of the tent, searching for weaknesses, careful never to give an inch, always positioned for an imminent takeover.

None of this is new, mind you. Competition drives people of similar faiths regardless of discipline, whether religious in nature or scientific—and has since the beginning of recorded history. The tendency to see our own experience as definitive seems to be drawn equally from the limitations of human perception and the enormous visionary expanses of our imaginations.

The battle between science and religion is certainly not new. Competing worldviews are a very necessary and important part of human culture, frequently, and unfortunately, articulated as a debate between superstition and enlightenment—but is it really that simple?

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Galileo, Copernicus and Johannes Kepler stated the radical belief that the Earth revolved around the sun and was not the center of the universe, while the Church asserted that it was. Neither position was new. Aristarchus of Samos believed that the earth moved around the sun as early as the 3rd century B.C. Most ancient Greek philosophers disagreed, however, doing so on the basis of mathematics, not religious faith. The spherical shape of the earth was known as far back as 500 B.C.—two thousand years before Columbus. The Epicureans and the atomists in pre-Christian cultures believed that the universe was comprised of atoms and void—an idea held by the ancient cultures of Greece and the Buddhists of India.

These were attempts to offer a scientific, natural explanation for the origin of the universe, attempts that very closely resemble modern scientific thought—Ideas that weren’t confirmed by European scientists until more than twenty-four-hundred years later in the 20th century.

During the golden age of what is sometimes called the Islamic renaissance, from about 700 A.D. to 1300 A.D., Muslim philosophers, mathematicians, architects and scientists added significantly to the increase in global knowledge—pre-dating the European renaissance by nearly a thousand years.

Jews lived safely and in peace in Muslim countries dating to the 7th century A.D. and shared similar religious and cultural values, as well as founding patriarchs like Moses, who’s mentioned in the Quran more than any other figure, as well as Jesus who is regarded as a prophet. The children of Israel are esteemed as an important concept in Muslim thought—with the story of Esau and Jacob in the Hebrew Bible telling a story of two brothers fighting in the womb,(Israel and the pre – Babylonian culture from which they were drawn) being so closely linked that they were twins attached at the heel.

All of these cultural, scientific and religious ideas existed not hundreds of years before Europe’s own emergence from the dark ages, but thousands of years prior. Our predominately western Eurocentric worldview has misinterpreted and misunderstood the culture and traditions of the Middle East and non–European cultures dating to the time of Christ and before—including ancient Israel and early Christianity. It must be remembered, however, that both Greece and Rome were on the European continent and, as such, are a part of the long history of the West.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Galileo, Copernicus and Johannes Kepler stated the radical belief that the Earth revolved around the sun and was not the center of the universe, while the Church asserted that it was. Neither position was new. Aristarchus of Samos believed that the earth moved around the sun as early as the 3rd century B.C. Most ancient Greek philosophers disagreed, however, doing so on the basis of mathematics, not religious faith. The spherical shape of the earth was known as far back as 500 B.C.—two thousand years before Columbus. The Epicureans and the atomists in pre-Christian cultures believed that the universe was comprised of atoms and void—an idea held by the ancient cultures of Greece and the Buddhists of India.

These were attempts to offer a scientific, natural explanation for the origin of the universe, attempts that very closely resemble modern scientific thought—Ideas that weren’t confirmed by European scientists until more than twenty-four-hundred years later in the 20th century.

During the golden age of what is sometimes called the Islamic renaissance, from about 700 A.D. to 1300 A.D., Muslim philosophers, mathematicians, architects and scientists added significantly to the increase in global knowledge—pre-dating the European renaissance by nearly a thousand years.

Jews lived safely and in peace in Muslim countries dating to the 7th century A.D. and shared similar religious and cultural values, as well as founding patriarchs like Moses, who’s mentioned in the Quran more than any other figure, as well as Jesus who is regarded as a prophet. The children of Israel are esteemed as an important concept in Muslim thought—with the story of Esau and Jacob in the Hebrew Bible telling a story of two brothers fighting in the womb,(Israel and the pre – Babylonian culture from which they were drawn) being so closely linked that they were twins attached at the heel.

All of these cultural, scientific and religious ideas existed not hundreds of years before Europe’s own emergence from the dark ages, but thousands of years prior. Our predominately western Eurocentric worldview has misinterpreted and misunderstood the culture and traditions of the Middle East and non–European cultures dating to the time of Christ and before—including ancient Israel and early Christianity. It must be remembered, however, that both Greece and Rome were on the European continent and, as such, are a part of the long history of the West.

With the decline and fall of the Roman Empire and its social and political structures in 476 A.D., Europe descended into anarchy and chaos. This would ultimately be exponentially compounded by a Black Plague that killed more than one hundred million people, better than half of its total population. The plague left an emerging European culture bereft of the necessary labor force, artisans, craftsmen and intellectuals to sustain a healthy societal progression and growth.

The Barbarians that stormed the gates of a collapsing Rome inherited its remains—and much of the European Continent descended into a thousand years of darkness. Beginning a period when Kings oftentimes could neither read nor write, and ruled over an illiterate populace, the sole source of education became priests and scribes, just as it had been in the time of Jesus, with power shared between an illiterate royalty and an increasingly politicized Church. Both wielded power in a way that was a corrupt variation of the first century relationship between the Jewish ruling class of King Herod and his descendants—and the scribes and Pharisees that ruled over Jesus and his contemporaries.

Contrary to popular myth among western nations, it wasn’t Christianity that saved Europe from the Dark and Middle Ages, but the reclamation of the philosophy and science of the Greeks and Romans, which led to the period in European history called “The Age of Reason.” This became the basis of our own constitutional democracy and the intellectual lifeblood for the founders. If Christianity was the moral foundation for American culture, Greece was its political and Intellectual bedrock.

For more than sixteen centuries, there have been attempts to wed Christianity with the state and, in the process; it has tended to either diminish God as a reflection of the body politic—or elevated politics to the level of the divine. Either way, it was, and is, a prescription for tyranny, to say nothing of idolatry, with a long miserable history.

The Founding Fathers understood the necessity of placing freedom outside the bounds of the government, stating that man had inalienable rights endowed by their creator. If government was the source of our freedom, then it could just as easily be taken away by that same government. But if freedom was God given, then no man or king could violate it. Jefferson wasn’t quoting scripture or Christian tradition however—the idea of unalienable rights came in their earliest form from the Greek Stoics, dating to the 3rd century before Christ. How ironic, that a society that was so openly comfortable with homosexuality could play such a fundamental role in the evolution of European and American culture and the Judeo -Christian values that we claim to hold so dear! (This could be a point at which Evangelicals begin to ponder the relationship between religious belief and the greater historical reality that under-girds it.)

None of this is unique to Europeans, nor is it meant to give a pass to modern Islamic extremists or undermine American and European accomplishments. It is, instead, an attempt to challenge the easy assumptions and political and religious propaganda that is typical of cultures of all kinds—including militant atheists or equally militant Theists.

The Barbarians that stormed the gates of a collapsing Rome inherited its remains—and much of the European Continent descended into a thousand years of darkness. Beginning a period when Kings oftentimes could neither read nor write, and ruled over an illiterate populace, the sole source of education became priests and scribes, just as it had been in the time of Jesus, with power shared between an illiterate royalty and an increasingly politicized Church. Both wielded power in a way that was a corrupt variation of the first century relationship between the Jewish ruling class of King Herod and his descendants—and the scribes and Pharisees that ruled over Jesus and his contemporaries.

Contrary to popular myth among western nations, it wasn’t Christianity that saved Europe from the Dark and Middle Ages, but the reclamation of the philosophy and science of the Greeks and Romans, which led to the period in European history called “The Age of Reason.” This became the basis of our own constitutional democracy and the intellectual lifeblood for the founders. If Christianity was the moral foundation for American culture, Greece was its political and Intellectual bedrock.

For more than sixteen centuries, there have been attempts to wed Christianity with the state and, in the process; it has tended to either diminish God as a reflection of the body politic—or elevated politics to the level of the divine. Either way, it was, and is, a prescription for tyranny, to say nothing of idolatry, with a long miserable history.

The Founding Fathers understood the necessity of placing freedom outside the bounds of the government, stating that man had inalienable rights endowed by their creator. If government was the source of our freedom, then it could just as easily be taken away by that same government. But if freedom was God given, then no man or king could violate it. Jefferson wasn’t quoting scripture or Christian tradition however—the idea of unalienable rights came in their earliest form from the Greek Stoics, dating to the 3rd century before Christ. How ironic, that a society that was so openly comfortable with homosexuality could play such a fundamental role in the evolution of European and American culture and the Judeo -Christian values that we claim to hold so dear! (This could be a point at which Evangelicals begin to ponder the relationship between religious belief and the greater historical reality that under-girds it.)

None of this is unique to Europeans, nor is it meant to give a pass to modern Islamic extremists or undermine American and European accomplishments. It is, instead, an attempt to challenge the easy assumptions and political and religious propaganda that is typical of cultures of all kinds—including militant atheists or equally militant Theists.

In recent times, atheists have become increasingly militant in no small part because religion—primarily America’s Christian right—have become increasingly political and militant, oftentimes expressing a socio-political Gospel articulated in militaristic and ideological terms. On the other hand, if religion poisons everything, as the book by well-known political writer and atheist, Christopher Hitchens, suggests, then the overwhelming majority of history’s greatest moral thinkers and scientists are guilty as well.

From Aristotle to Copernicus and from Jefferson to Einstein, religion has played a fundamental role in shaping the moral philosophy and sciences of all great cultures. Those few societies that intentionally made atheism the preferred religion of the state have produced genocidal atrocities so monstrous that they surpass all of the crimes of religious-centered cultures combined!

Does this mean that atheism is the enemy? None of these cultures were, in fact, motivated by their atheistic faith, although you can find a reasonable, but tenuous, connection between the two. It’s clear that it’s possible to be an atheist while still maintaining a certain morality as a person. In the same way, the religious individual can be both a devout believer, and understood as such in the light of their own spiritual interpretation, and still be morally bankrupt.

A better candidate for enemy status than our individual belief systems is, more reasonably, human nature itself! An idea reaffirmed in the Biblical tradition and found in the very first few chapters of Genesis thousands of years in advance of the enlightenment.

Science and religion share a common belief in something like the perfectibility of human nature—with religion proffering God as the source of morality and change—and science prescribing the scientific method as the basis for enlightenment.

Judaism was heavily influenced by the neo–scientific and philosophical methods of the Persians and the Greeks, both of which ultimately played a role in the evolution of Jewish culture. This historical confluence of religious faith and science found its moral apex in the first century Palestine—not in conflict with one another, but in concert—and was reflected in the life and teachings of Jesus, arguably history’s most influential moral thinker. Jesus could be seen as (and almost certainly was) a kind of savant, who’s perceptions regarding human nature and morality were every bit as influential and no less observably true than Freud’s. Freud’s own use of Id, Ego and Super Ego are really variations of the much older Greek and Jewish traditions of body, soul and spirit. (The apparent gulf between science and faith may be a good deal narrower than we are prone to believe.)

The unfortunate problem for both devout Christians and Jews is one of historical literalism versus the deeper truths that permeate scripture—perhaps better understood as the ability to only read the notes on the staff, instead of the music that they represent. For science, the problem is one of the incremental increases in knowledge gained by the scientific method, placing morality at the long end of an inferential trail—or morality deferred.

The gun lobby likes to say, “guns don’t kill people, people kill people” and they are right. Ideas don’t kill people either but they are the starting place—beginning in the very deepest recesses of the soul of man—as the most famous of all ancient Jewish teachers stated so powerfully more than two thousand years ago!

Mark Magula

From Aristotle to Copernicus and from Jefferson to Einstein, religion has played a fundamental role in shaping the moral philosophy and sciences of all great cultures. Those few societies that intentionally made atheism the preferred religion of the state have produced genocidal atrocities so monstrous that they surpass all of the crimes of religious-centered cultures combined!

Does this mean that atheism is the enemy? None of these cultures were, in fact, motivated by their atheistic faith, although you can find a reasonable, but tenuous, connection between the two. It’s clear that it’s possible to be an atheist while still maintaining a certain morality as a person. In the same way, the religious individual can be both a devout believer, and understood as such in the light of their own spiritual interpretation, and still be morally bankrupt.

A better candidate for enemy status than our individual belief systems is, more reasonably, human nature itself! An idea reaffirmed in the Biblical tradition and found in the very first few chapters of Genesis thousands of years in advance of the enlightenment.

Science and religion share a common belief in something like the perfectibility of human nature—with religion proffering God as the source of morality and change—and science prescribing the scientific method as the basis for enlightenment.

Judaism was heavily influenced by the neo–scientific and philosophical methods of the Persians and the Greeks, both of which ultimately played a role in the evolution of Jewish culture. This historical confluence of religious faith and science found its moral apex in the first century Palestine—not in conflict with one another, but in concert—and was reflected in the life and teachings of Jesus, arguably history’s most influential moral thinker. Jesus could be seen as (and almost certainly was) a kind of savant, who’s perceptions regarding human nature and morality were every bit as influential and no less observably true than Freud’s. Freud’s own use of Id, Ego and Super Ego are really variations of the much older Greek and Jewish traditions of body, soul and spirit. (The apparent gulf between science and faith may be a good deal narrower than we are prone to believe.)

The unfortunate problem for both devout Christians and Jews is one of historical literalism versus the deeper truths that permeate scripture—perhaps better understood as the ability to only read the notes on the staff, instead of the music that they represent. For science, the problem is one of the incremental increases in knowledge gained by the scientific method, placing morality at the long end of an inferential trail—or morality deferred.

The gun lobby likes to say, “guns don’t kill people, people kill people” and they are right. Ideas don’t kill people either but they are the starting place—beginning in the very deepest recesses of the soul of man—as the most famous of all ancient Jewish teachers stated so powerfully more than two thousand years ago!

Mark Magula