Summer, 1970 - "Fishing with Alligators"

It was a hot summer day. The weather was humid, as usual. The only thing that made it tolerable was a late afternoon thunderstorm. The combination of rain and cloud cover cooled the air, and with the sun hidden behind the haze, the temperature fell to manageable levels. My father asked me if I wanted to go out to the sawgrass, near the everglades, to do some fishing. I said yes, and he, my mom and I packed into the car, a mid-sixties flamingo pink Lincoln Continental, and began driving west to a familiar spot where we frequently fished. There were only a few hours of light left before evening, a time when the bigger fish were more likely to be active, meaning that, with a little luck, we might catch a few.

At the time, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida was a seasonal town. Between January and April the snowbirds flew in from the North hoping to get away from the winter cold. The college kids flocked to its beaches, with Ft. Lauderdale being a primary destination for spring breakers. In 1960, the film “Where the Boys Are” was shot here and had become a major hit, turning the city into the place to be when school let out for the Easter holiday. But, after the season ended, the city returned to its slower place, and with it came the heat.

In those days air-conditioning was still reasonably rare and most Floridians learned to live with the sweltering temperatures in houses that were built specifically to deal with the unique demands of the sub-tropical environment. Homes were built at S. E. angles to capture the cool breezes that came off the ocean as they moved inland. Large overhangs sheltered walls of jalousie windows which could be opened ceiling to floor, maximizing the air flow throughout. Terrazzo floors were made from a combination of materials, granite, glass, marble and quartz and remained cool to the touch even in the hottest weather, with vaulted ceilings that were designed to draw the hot air upward away from the living spaces. That, and floor fans situated in every room, made the summer heat manageable. But the rest of the year, between late September and early June, the weather was near perfect.

I moved there with my family as Christmas passed and the New Year signaled the end of the 1960’s. Within the first few days of the new decade my father and I packed our van with as much as it could safely hold and left the cold, small, Eastern Pennsylvania town behind—with the rest of the family set to follow once we settled. As we drove off, the temperature was a freezing thirteen degrees below zero (factoring in wind chill). When we hit Ohio it dropped even further—and the gallon of milk that set next to the van’s heater froze like a rock.

We drove through the treacherous mountains of Tennessee on roads covered in ice and snow, often without any protective guardrails. With every passing eighteen wheeler the wind caused our van to sway back and forth, with a precipitous drop of hundreds of feet looming just to our right. Two very long days later, we hit Ft. Lauderdale.

At the time, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida was a seasonal town. Between January and April the snowbirds flew in from the North hoping to get away from the winter cold. The college kids flocked to its beaches, with Ft. Lauderdale being a primary destination for spring breakers. In 1960, the film “Where the Boys Are” was shot here and had become a major hit, turning the city into the place to be when school let out for the Easter holiday. But, after the season ended, the city returned to its slower place, and with it came the heat.

In those days air-conditioning was still reasonably rare and most Floridians learned to live with the sweltering temperatures in houses that were built specifically to deal with the unique demands of the sub-tropical environment. Homes were built at S. E. angles to capture the cool breezes that came off the ocean as they moved inland. Large overhangs sheltered walls of jalousie windows which could be opened ceiling to floor, maximizing the air flow throughout. Terrazzo floors were made from a combination of materials, granite, glass, marble and quartz and remained cool to the touch even in the hottest weather, with vaulted ceilings that were designed to draw the hot air upward away from the living spaces. That, and floor fans situated in every room, made the summer heat manageable. But the rest of the year, between late September and early June, the weather was near perfect.

I moved there with my family as Christmas passed and the New Year signaled the end of the 1960’s. Within the first few days of the new decade my father and I packed our van with as much as it could safely hold and left the cold, small, Eastern Pennsylvania town behind—with the rest of the family set to follow once we settled. As we drove off, the temperature was a freezing thirteen degrees below zero (factoring in wind chill). When we hit Ohio it dropped even further—and the gallon of milk that set next to the van’s heater froze like a rock.

We drove through the treacherous mountains of Tennessee on roads covered in ice and snow, often without any protective guardrails. With every passing eighteen wheeler the wind caused our van to sway back and forth, with a precipitous drop of hundreds of feet looming just to our right. Two very long days later, we hit Ft. Lauderdale.

Ft. Lauderdale was as different from the small town of Sharon, Pennsylvania, with its harsh winters and smoky steel mills, as one could imagine. It was a near perfect 70 degrees with a subtle breeze, large, green Palm trees and exotic, yellow-and-orange tropical plants that were set off against deep blue skies dotted with white clouds, all of which created a beautiful landscape of exploding colors. It was another world, with what appeared to be an endless spring and summer season.

When most Americans were wearing layers of clothing in an effort to keep warm, South Florida was something akin to paradise. You could play baseball, basketball, golf and just about any other sport year round, including swimming, skiing and surfing. There were other oddities; bugs the size of tennis balls, native panthers, bears, poisonous snakes, the river of grass known as the Everglades—and the rarest of the rare, crocodiles.

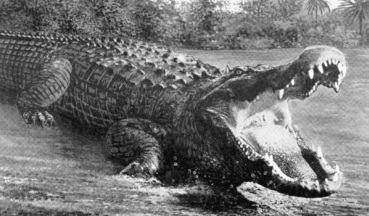

One of the most interesting occupants was a large armored reptile, black in color, reaching potential lengths of sixteen feet and weighing as much as fifteen hundred pounds. It had been hunted to the point of extinction in less than a hundred years. There had been a time when alligators proliferated throughout much of the Southeastern U.S., but hunting for their hides had radically diminished their population. Even with such low numbers, alligators were common in the sawgrass and the Everglades, certainly not as common as they once had been, but, they were there. And on that late summer afternoon they were out in numbers, making their way to the shoreline to hunt the larger fish that were feeding on the smaller ones.

As we arrived at our favorite fishing spot it was apparent that a few other people had the same idea. There was an older couple a few dozen yards to our right, with a lone fisherman, about the same distance to our left—and then there was a man sitting in a large inner tube in the stretch of canal directly in front of us. It looked like his homemade float had been constructed from the inner-tube of a large truck tire and fitted with a seat made from a kind of rope-like netting, with a couple of holes large enough for his legs to fit through. He was sitting in the water; legs dangling unseen in the murky estuary below—with no less than a half dozen alligators within a short stone’s throw in either direction.

My father turned to me and said, “That guy must be an idiot”! My mother shook her head in agreement. I remember thinking, “What if an alligator attacks this guy right in front of us”? He was only about thirty feet into the water, which quickly dropped off and was maybe twenty feet deep. There was no telling what was lurking beneath the surface. The blackish water made visibility any greater than a foot impossible.

With the day nearing its end, I decided to get as much fishing in as I could. It was then that I spotted a dead fish that had partially dried up. There was an alligator about six feet long in the water directly in front of me. I decided to bait my hook with the dead fish and see if I could cast it right in front of him—which I accomplished with an almost perfect throw. The gator sat motionless, and then casually grabbed the bait in its jaws and returned to its previous state of immobility, as though nothing had happened. I determined to test the animal’s strength by pulling on the line. With each tug it became clear that I was overmatched, the alligator floated there, as though no force had been applied, having not budged an inch in our one-sided tug of war. He then slowly turned and without any additional exertion snapped my line like it didn’t exist. I was 155 pounds of athletic teenager, and I didn’t even register as an annoyance to this animal. It was a glimpse into the power of nature, and by comparison my relative insignificance.

When most Americans were wearing layers of clothing in an effort to keep warm, South Florida was something akin to paradise. You could play baseball, basketball, golf and just about any other sport year round, including swimming, skiing and surfing. There were other oddities; bugs the size of tennis balls, native panthers, bears, poisonous snakes, the river of grass known as the Everglades—and the rarest of the rare, crocodiles.

One of the most interesting occupants was a large armored reptile, black in color, reaching potential lengths of sixteen feet and weighing as much as fifteen hundred pounds. It had been hunted to the point of extinction in less than a hundred years. There had been a time when alligators proliferated throughout much of the Southeastern U.S., but hunting for their hides had radically diminished their population. Even with such low numbers, alligators were common in the sawgrass and the Everglades, certainly not as common as they once had been, but, they were there. And on that late summer afternoon they were out in numbers, making their way to the shoreline to hunt the larger fish that were feeding on the smaller ones.

As we arrived at our favorite fishing spot it was apparent that a few other people had the same idea. There was an older couple a few dozen yards to our right, with a lone fisherman, about the same distance to our left—and then there was a man sitting in a large inner tube in the stretch of canal directly in front of us. It looked like his homemade float had been constructed from the inner-tube of a large truck tire and fitted with a seat made from a kind of rope-like netting, with a couple of holes large enough for his legs to fit through. He was sitting in the water; legs dangling unseen in the murky estuary below—with no less than a half dozen alligators within a short stone’s throw in either direction.

My father turned to me and said, “That guy must be an idiot”! My mother shook her head in agreement. I remember thinking, “What if an alligator attacks this guy right in front of us”? He was only about thirty feet into the water, which quickly dropped off and was maybe twenty feet deep. There was no telling what was lurking beneath the surface. The blackish water made visibility any greater than a foot impossible.

With the day nearing its end, I decided to get as much fishing in as I could. It was then that I spotted a dead fish that had partially dried up. There was an alligator about six feet long in the water directly in front of me. I decided to bait my hook with the dead fish and see if I could cast it right in front of him—which I accomplished with an almost perfect throw. The gator sat motionless, and then casually grabbed the bait in its jaws and returned to its previous state of immobility, as though nothing had happened. I determined to test the animal’s strength by pulling on the line. With each tug it became clear that I was overmatched, the alligator floated there, as though no force had been applied, having not budged an inch in our one-sided tug of war. He then slowly turned and without any additional exertion snapped my line like it didn’t exist. I was 155 pounds of athletic teenager, and I didn’t even register as an annoyance to this animal. It was a glimpse into the power of nature, and by comparison my relative insignificance.

With that humiliation behind me, I returned to fishing for something more reasonable, all the while keeping an eye on the half dozen or so gators that were converging closer to shore. Suddenly, out of the corner of my eye I saw a large black shape in the water. I heard my mother gasp “Oh my god!” and then my father said “Look at that!” Not more than thirty feet from the man in the homemade raft, a large alligator, the biggest that I had ever seen, surfaced…..and it was heading directly for him! Everyone on the shore froze; there was no shouting, no yelling “Get the hell out of there!” There was no time. Even if he had wanted to, there was no way to escape. I remember thinking “This guy’s going to die right in front of me! He’ll be ripped to shreds and eaten, maybe drug down into the water where he’ll disappear and never be seen again!”

There is that surreal moment when time freezes, but the brain continues to move with tremendous speed, taking in information and translating its meaning. There were, it seemed, infinite scenarios being played out in my head—and in that brief instant this enormous animal swam closer.

Alligators are ambush predators. They’ll wait, hidden just beneath the surface of the water, almost invisible, and when their prey is within reach of what are the most powerful jaws in all of the animal kingdom, they’ll strike! The man stranded in the middle of the canal represented nothing more than an opportunity to feed. It wasn’t fate at work, or the malicious nature of the giant reptile. The man had made a choice to disregard the potential danger—and the alligator saw a potential meal.

Before the 1940’s, recordkeeping of alligator attacks was sporadic at best. They were viewed as a nuisance to be shot and removed from human habitation, which kept expanding at a tremendous rate. As the population of Florida increased, the habitat for alligators decreased. By 1970, the same year that this event took place, they finally received protected status.

It was generally believed that alligator’s weren’t a threat to people, much in the same way that scientists viewed sharks in the early part of the twentieth century. Anecdotal evidence, however, suggested a different conclusion. Where these animals were unlikely to attack and consume humans, it did happen. They were large, very powerful, carnivorous, omnivores, meaning that if it was meat, they’d eat it. An opportunistic predator would take whatever presented itself—and the man floating helplessly in front of me provided the perfect opportunity!

The large animal moved forward, silently, while the other alligators in the area sat motionless. This was clearly the alpha male that dominated this territory. In most instances, his presence would signal retreat to the smaller alligators or risk becoming lunch. Alligators are cannibalistic; the bigger ones naturally keep their own population in check by killing them for food or in territorial disputes. In some instances, when a big alligator attacks and kills large prey, the smaller ones will provide assistance, holding the various parts of the animal in their jaws while the bigger one spins in a death roll, dismembering its victim. With alligators there is no altruism, the smaller ones assist in the hopes of eating the leftovers. That meant that if the big gator did attack, it could trigger a feeding frenzy.

There is that surreal moment when time freezes, but the brain continues to move with tremendous speed, taking in information and translating its meaning. There were, it seemed, infinite scenarios being played out in my head—and in that brief instant this enormous animal swam closer.

Alligators are ambush predators. They’ll wait, hidden just beneath the surface of the water, almost invisible, and when their prey is within reach of what are the most powerful jaws in all of the animal kingdom, they’ll strike! The man stranded in the middle of the canal represented nothing more than an opportunity to feed. It wasn’t fate at work, or the malicious nature of the giant reptile. The man had made a choice to disregard the potential danger—and the alligator saw a potential meal.

Before the 1940’s, recordkeeping of alligator attacks was sporadic at best. They were viewed as a nuisance to be shot and removed from human habitation, which kept expanding at a tremendous rate. As the population of Florida increased, the habitat for alligators decreased. By 1970, the same year that this event took place, they finally received protected status.

It was generally believed that alligator’s weren’t a threat to people, much in the same way that scientists viewed sharks in the early part of the twentieth century. Anecdotal evidence, however, suggested a different conclusion. Where these animals were unlikely to attack and consume humans, it did happen. They were large, very powerful, carnivorous, omnivores, meaning that if it was meat, they’d eat it. An opportunistic predator would take whatever presented itself—and the man floating helplessly in front of me provided the perfect opportunity!

The large animal moved forward, silently, while the other alligators in the area sat motionless. This was clearly the alpha male that dominated this territory. In most instances, his presence would signal retreat to the smaller alligators or risk becoming lunch. Alligators are cannibalistic; the bigger ones naturally keep their own population in check by killing them for food or in territorial disputes. In some instances, when a big alligator attacks and kills large prey, the smaller ones will provide assistance, holding the various parts of the animal in their jaws while the bigger one spins in a death roll, dismembering its victim. With alligators there is no altruism, the smaller ones assist in the hopes of eating the leftovers. That meant that if the big gator did attack, it could trigger a feeding frenzy.

When the alligator got within a few yards it dove down. I thought, “He’s going to grab him by the legs”! There could be no other plausible explanation for its actions. From the moment it first surfaced it never veered from its trajectory, heading dead on towards the helpless figure sitting stunned, in a glacial panic. We all stood on the shore; sure of the horror to come….and then…..there was nothing. Seconds passed….and then minutes—and nothing, not a ripple. Whatever the alligator’s intent, feeding didn’t seem to be his objective.

Maybe it was a territorial display intended to scare off any potential rivals. Whatever it was, it worked. The man made his way to the shore and the rest of us exhaled after what seemed like minutes of exhausted breathlessness. As the night came, we left for home. Predators are far more active at night than in the day—and no one was willing to push the boundaries any further. If fate had been tempted, its response had been gracious. It could have easily been otherwise.

I’ve learned to appreciate nature for what it is, beautiful, in part because it’s dangerous. Its unpredictability makes the world more exotic, and as such, more tempting, more meaningful, and endlessly compelling!

Mark Magula

Maybe it was a territorial display intended to scare off any potential rivals. Whatever it was, it worked. The man made his way to the shore and the rest of us exhaled after what seemed like minutes of exhausted breathlessness. As the night came, we left for home. Predators are far more active at night than in the day—and no one was willing to push the boundaries any further. If fate had been tempted, its response had been gracious. It could have easily been otherwise.

I’ve learned to appreciate nature for what it is, beautiful, in part because it’s dangerous. Its unpredictability makes the world more exotic, and as such, more tempting, more meaningful, and endlessly compelling!

Mark Magula

|

|

|