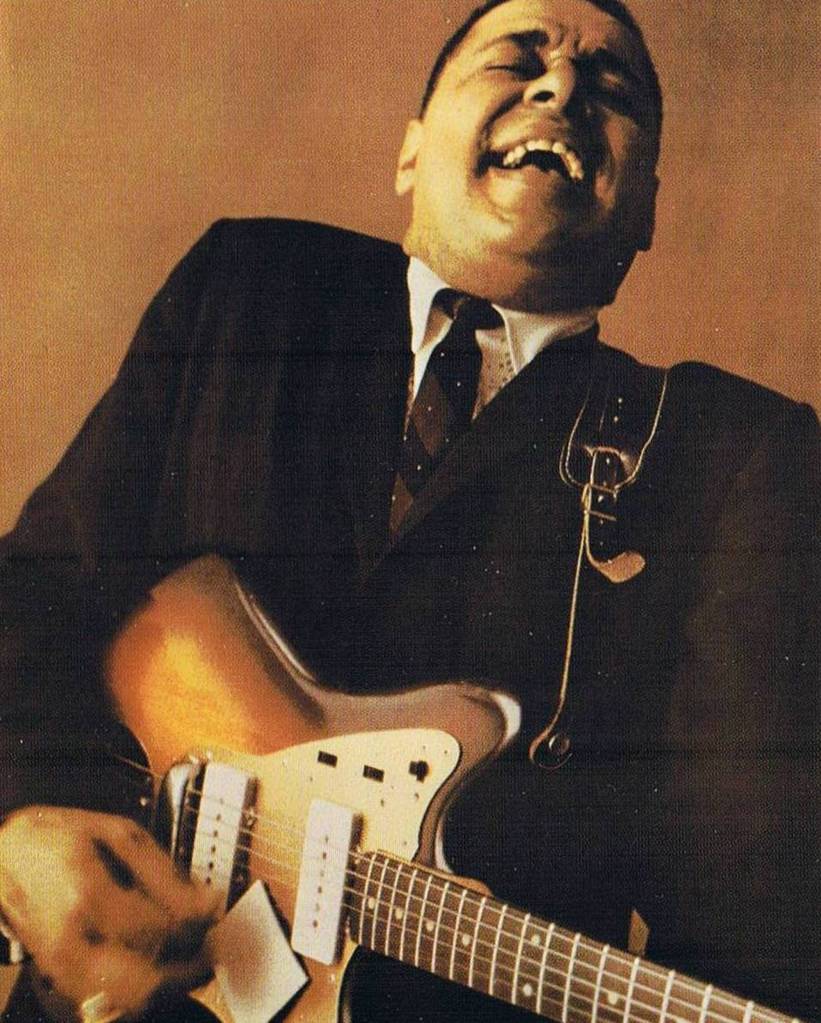

Mickey Baker

"Goin' To Kansas City"

Mickey Baker - Going To Kansas City

“Dig this!” Mickey Baker began making records, way back, in 1949, five years before my blessed birth, when there was no rock& roll, no Elvis, no Beatles. There was rhythm & blues, and there were blues and country, jazz and swing. Other forms existed, but they didn’t count. This was pure American music that could have originated no place else.

Mickey was half Black, half White, and traversed a range as a guitarist between the blues and rhythm when rhythm & blues was a swinging cousin to deep delta blues—and bluesy, swinging jazz.

Mickey, like a lot of Black musicians, played the kind of music that was popular in Black clubs, and on post-war, Black radio—a little Charlie Parker, some T Bone Walker-style-blues, even Lightnin’ Hopkins, whatever was called for, Mickey could handle it. He was like The Black Les Paul (The man, not the guitar.) In 1959 Mickey struck gold with the top ten hit “Love is Strange,” recorded under the names; Mickey and Sylvia, a duet he’d formed with one of his guitar students, giving even more credence to the Les Paul/Mary Ford connection.

I became aware of Baker through his Mel Bay jazz books, which were, and still are, some of the best jazz educational material for the rock or soul guitarist, with a hankering to learn some jazz, while trying not to sound like a fool on the gig as you scuffle to play Tad Dameron’s “Lady Bird”—an uneasy sensation I had with my own transitional phase from Rock guitar ace, to something more sophisticated. Mickey’s two volumes were like essential Jiu-jitsu moves, preparing the fistic novice for a street fight. Armed with these moves, these jazz chords, Mickey’s jiu-jitsu guitar could give you the necessary bravery to confront a kind of blues that was more than just a 1 -4- 5 progression.

On the song, “Kansas City,” an old r&b chestnut that everybody from Count Basie and Trini Lopez, to The Beatles, recorded, Mickey lays down a laid-back soulful vocal, that’s unassumingly cool and conversational, like so much street corner talking. The band, for this particular recording contains two other jazz and blues guitarist—legends both—Tiny Grimes and Louis Meyers. Meyers was in Little Walter’s original band, The Aces, playing on all those classic Walter records, like “My Babe” and “Lights out,” to name just a few. And Tiny Grimes, he of the 4 string tenor guitar, played in a trio with the greatest virtuoso jazz ever produced, the blind pianist, Art Tatum—as well as, too many other artists to name in a short article. Tiny Grimes takes flight first and plays a warm, expressive solo, filled with classic after hours guitar and full-bodied jazz chords. Then Mickey slides in and precedes to play one of the finest guitar solos I’ve ever heard. It’s modern and traditional, and unexpectedly dynamic and playful. It’s a single chorus, maybe two, of humorous bravado, chops, and soul.

None of the music on this album, which was recorded in 1973, is the product of big money production techniques but has a loose jam session feel, the kind you might’ve heard in Harlem club or on Chicago’s South Side, anytime between the late 1940's and the mid-1970’s.

By 1973, when the music was recorded, it was already passe,’ certainly, that was the case for a younger audience, except, maybe, in hardcore blues, and old-school r&b circles, where real blues was sought after for its authenticity. Authenticity was money, aesthetically speaking, for young White kids, looking to tap into some of that effortless mojo and sensuality that was, almost always a part of Black popular music.

Mickey’s career was long and punctuated by sporadic revivals, the occasional recording as a solo artist, and session work. He eventually moved to France in the 1980’s, where he remained for the rest of his life, until his death at 87. Six wives and an expansive career that lasted 50 years, many good recordings, and those two guitar books, those are his lasting legacy. To understand the impact of Mickey’s jazz guitar, how-to books, ask how many older players used them as a jumping off point, into the big stream of jazz music. And, if that’s not enough, go listen to Mickey’s solo on “Kansas City.” For guitar players and hardcore lovers of post-war blues, jazz, and r&b, that’s more than enough.

Mark Magula

“Dig this!” Mickey Baker began making records, way back, in 1949, five years before my blessed birth, when there was no rock& roll, no Elvis, no Beatles. There was rhythm & blues, and there were blues and country, jazz and swing. Other forms existed, but they didn’t count. This was pure American music that could have originated no place else.

Mickey was half Black, half White, and traversed a range as a guitarist between the blues and rhythm when rhythm & blues was a swinging cousin to deep delta blues—and bluesy, swinging jazz.

Mickey, like a lot of Black musicians, played the kind of music that was popular in Black clubs, and on post-war, Black radio—a little Charlie Parker, some T Bone Walker-style-blues, even Lightnin’ Hopkins, whatever was called for, Mickey could handle it. He was like The Black Les Paul (The man, not the guitar.) In 1959 Mickey struck gold with the top ten hit “Love is Strange,” recorded under the names; Mickey and Sylvia, a duet he’d formed with one of his guitar students, giving even more credence to the Les Paul/Mary Ford connection.

I became aware of Baker through his Mel Bay jazz books, which were, and still are, some of the best jazz educational material for the rock or soul guitarist, with a hankering to learn some jazz, while trying not to sound like a fool on the gig as you scuffle to play Tad Dameron’s “Lady Bird”—an uneasy sensation I had with my own transitional phase from Rock guitar ace, to something more sophisticated. Mickey’s two volumes were like essential Jiu-jitsu moves, preparing the fistic novice for a street fight. Armed with these moves, these jazz chords, Mickey’s jiu-jitsu guitar could give you the necessary bravery to confront a kind of blues that was more than just a 1 -4- 5 progression.

On the song, “Kansas City,” an old r&b chestnut that everybody from Count Basie and Trini Lopez, to The Beatles, recorded, Mickey lays down a laid-back soulful vocal, that’s unassumingly cool and conversational, like so much street corner talking. The band, for this particular recording contains two other jazz and blues guitarist—legends both—Tiny Grimes and Louis Meyers. Meyers was in Little Walter’s original band, The Aces, playing on all those classic Walter records, like “My Babe” and “Lights out,” to name just a few. And Tiny Grimes, he of the 4 string tenor guitar, played in a trio with the greatest virtuoso jazz ever produced, the blind pianist, Art Tatum—as well as, too many other artists to name in a short article. Tiny Grimes takes flight first and plays a warm, expressive solo, filled with classic after hours guitar and full-bodied jazz chords. Then Mickey slides in and precedes to play one of the finest guitar solos I’ve ever heard. It’s modern and traditional, and unexpectedly dynamic and playful. It’s a single chorus, maybe two, of humorous bravado, chops, and soul.

None of the music on this album, which was recorded in 1973, is the product of big money production techniques but has a loose jam session feel, the kind you might’ve heard in Harlem club or on Chicago’s South Side, anytime between the late 1940's and the mid-1970’s.

By 1973, when the music was recorded, it was already passe,’ certainly, that was the case for a younger audience, except, maybe, in hardcore blues, and old-school r&b circles, where real blues was sought after for its authenticity. Authenticity was money, aesthetically speaking, for young White kids, looking to tap into some of that effortless mojo and sensuality that was, almost always a part of Black popular music.

Mickey’s career was long and punctuated by sporadic revivals, the occasional recording as a solo artist, and session work. He eventually moved to France in the 1980’s, where he remained for the rest of his life, until his death at 87. Six wives and an expansive career that lasted 50 years, many good recordings, and those two guitar books, those are his lasting legacy. To understand the impact of Mickey’s jazz guitar, how-to books, ask how many older players used them as a jumping off point, into the big stream of jazz music. And, if that’s not enough, go listen to Mickey’s solo on “Kansas City.” For guitar players and hardcore lovers of post-war blues, jazz, and r&b, that’s more than enough.

Mark Magula