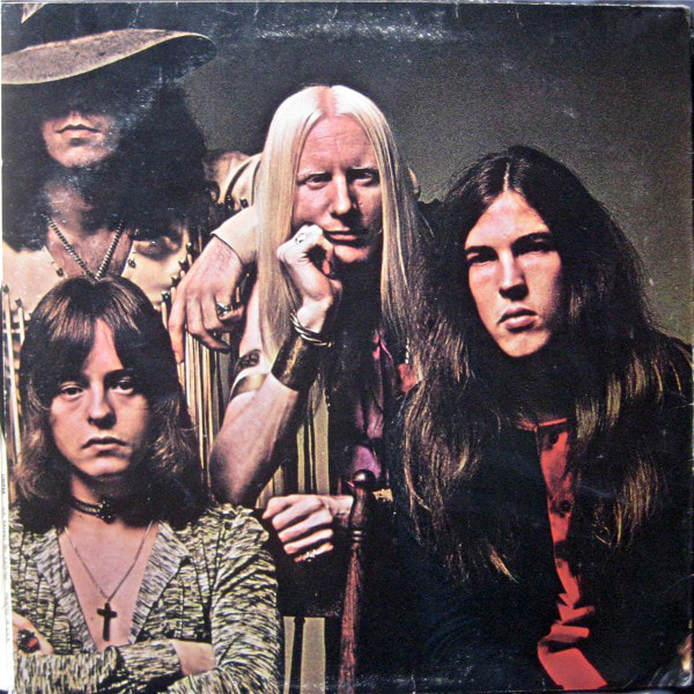

Johnny Winter and, 1970

Johnny Winter and, 1970, pt. 1

There was something about that sound. It was a siren's call. But only a few people seemed to hear it. I can remember walking into the big open space at Pirates World—in the concert area—and hearing a guitar playing these thick, sinewy, lines, flowing like rivulets of liquescent steel. That’s how the sound poured out of a bank of amplifiers that took up half the stage. The guitar wasn’t just loud. Although, it was loud. It was, to my ears, at least, almost symphonic.

The guitarist turned out to be the roadie for the opening act, a band called Tin house, a bunch of South Florida boys, with a serious ear for the newly emerging hard rock music that gave birth to Zeppelin, Cream, Hendrix, Cactus, and Deep Purple. Floyd Radford, the lead guitarist with Tin House, had been with Edgar Winter’s White Trash, tearing up the anthemic bar-band rock of “Keep Playing That Rock & Roll,” on Edgar and The Trash boys, first recording of the same name. Floyd Radford was only a couple years older than I was, but he was already one of the best rock guitarists in the world.

After a short break, Tin House came on and devastated the crowd with one hard rock gem after another, playing a kind of heavy, blues-based rock, with plenty of Radford’s stunning lead guitar work. At one point the lead singer said the band was gonna play the blues and make it rain, and, sure enough, it did. We could hear the downpour beating against the tin roof that covered the arena. That was our validation. The whole experience, the music, the band, Radford’s guitar playing, were sufficiently mystical to make me a believer in the shamanistic powers of rock & roll. Good. Heavy. Rock & roll.

The thought that rock & roll could be mystical, seems quaint now. But then, the music quivered through my body, like intense lust—and love—the perfect union of soul & steel, as unpredictable, then, as swimming in a modest sized pool with a 10 ft. bull shark. It was that element of danger, mixed with an electrifying unpredictability, that made rock & roll, great. Especially, if you were 16.

At 16, my brain and body were on fire for that sound. I had to possess it. Hearing it was almost as intense as the most intense sex. Not that I was a Lothario, I wasn’t. It was the power of the music, as cliched as that sounds. That was the essence of the siren’s call.

After about a half hour of the roadies clearing and resetting the stage, “Johnny Winter and” plugged in and began to play. The “and” part of Johnny Winter and, was essentially, The McCoys. One of the many one-hit wonders of 1965, featuring a very young Rick Derringer. In the ensuing 4 years since Hang on Sloopy, Derringer became one of the finest rock guitarists in the world, as well as a solid producer and songwriter. It was as a guitarist, however, where Derringer really shined.

Randy Jo Hobbs on bass, was a significant talent in his own right. Hobbs went on to play with Edgar Winter, in what was Edgar’s finest band, the version of White Trash from the double live album, “Roadwork.” Hobbs was a McCoy, too, for 4 years—and recorded with Hendrix, which was as high up the guitaristic food-chain as you could possibly hope to obtain.

The rhythm end of Johnny Winter and was Bobby Caldwell. Caldwell was one of the finest little-known rock drummers in the history of the music. A veritable rock and roll/big band/r&b drumming powerhouse. He was almost an Allman Brother, although, I believe it was Caldwell’s choice not to join the band. He was also the driving force, rhythmically and creatively, behind cult legend-super-group, “Captain Beyond.” Caldwell was that rarest of rare rock drummers, one who could make the music swing, unlike just about every other drummer in the rock music of the time, Carmine Appice being the possible exception.

With Derringer on second lead guitar, challenging Winter lick for lick, Randy Jo Hobbs holding down the bottom, and Caldwell, driving the band in a way that should be a template for any would-be rock drummer, Winter had his best band ever. Which would be preserved forever, on a live recording, being made right in front of us.

Mark Magula

There was something about that sound. It was a siren's call. But only a few people seemed to hear it. I can remember walking into the big open space at Pirates World—in the concert area—and hearing a guitar playing these thick, sinewy, lines, flowing like rivulets of liquescent steel. That’s how the sound poured out of a bank of amplifiers that took up half the stage. The guitar wasn’t just loud. Although, it was loud. It was, to my ears, at least, almost symphonic.

The guitarist turned out to be the roadie for the opening act, a band called Tin house, a bunch of South Florida boys, with a serious ear for the newly emerging hard rock music that gave birth to Zeppelin, Cream, Hendrix, Cactus, and Deep Purple. Floyd Radford, the lead guitarist with Tin House, had been with Edgar Winter’s White Trash, tearing up the anthemic bar-band rock of “Keep Playing That Rock & Roll,” on Edgar and The Trash boys, first recording of the same name. Floyd Radford was only a couple years older than I was, but he was already one of the best rock guitarists in the world.

After a short break, Tin House came on and devastated the crowd with one hard rock gem after another, playing a kind of heavy, blues-based rock, with plenty of Radford’s stunning lead guitar work. At one point the lead singer said the band was gonna play the blues and make it rain, and, sure enough, it did. We could hear the downpour beating against the tin roof that covered the arena. That was our validation. The whole experience, the music, the band, Radford’s guitar playing, were sufficiently mystical to make me a believer in the shamanistic powers of rock & roll. Good. Heavy. Rock & roll.

The thought that rock & roll could be mystical, seems quaint now. But then, the music quivered through my body, like intense lust—and love—the perfect union of soul & steel, as unpredictable, then, as swimming in a modest sized pool with a 10 ft. bull shark. It was that element of danger, mixed with an electrifying unpredictability, that made rock & roll, great. Especially, if you were 16.

At 16, my brain and body were on fire for that sound. I had to possess it. Hearing it was almost as intense as the most intense sex. Not that I was a Lothario, I wasn’t. It was the power of the music, as cliched as that sounds. That was the essence of the siren’s call.

After about a half hour of the roadies clearing and resetting the stage, “Johnny Winter and” plugged in and began to play. The “and” part of Johnny Winter and, was essentially, The McCoys. One of the many one-hit wonders of 1965, featuring a very young Rick Derringer. In the ensuing 4 years since Hang on Sloopy, Derringer became one of the finest rock guitarists in the world, as well as a solid producer and songwriter. It was as a guitarist, however, where Derringer really shined.

Randy Jo Hobbs on bass, was a significant talent in his own right. Hobbs went on to play with Edgar Winter, in what was Edgar’s finest band, the version of White Trash from the double live album, “Roadwork.” Hobbs was a McCoy, too, for 4 years—and recorded with Hendrix, which was as high up the guitaristic food-chain as you could possibly hope to obtain.

The rhythm end of Johnny Winter and was Bobby Caldwell. Caldwell was one of the finest little-known rock drummers in the history of the music. A veritable rock and roll/big band/r&b drumming powerhouse. He was almost an Allman Brother, although, I believe it was Caldwell’s choice not to join the band. He was also the driving force, rhythmically and creatively, behind cult legend-super-group, “Captain Beyond.” Caldwell was that rarest of rare rock drummers, one who could make the music swing, unlike just about every other drummer in the rock music of the time, Carmine Appice being the possible exception.

With Derringer on second lead guitar, challenging Winter lick for lick, Randy Jo Hobbs holding down the bottom, and Caldwell, driving the band in a way that should be a template for any would-be rock drummer, Winter had his best band ever. Which would be preserved forever, on a live recording, being made right in front of us.

Mark Magula