James Brown and the Art of the Indefinite Rhythm

A short time after James Brown died, I found myself listening to Public Radio. It was an interview with a young African American woman, a social activist who said Brown had been meaningful to her parents, but not so much for her. For her, Brown was a symbol of another time, before she came of age. It was Brown’s musical descendants that influenced her, although she didn’t really seem to recognize it. She heard some limited connection, but was essentially indifferent to his impact on the culture. Too bad, Butane James was every bit as influential as Elvis, even if the culture never fully recognized it.

The two men were fast friends, singing gospel music in their off hours--in hotel rooms, or wherever a piano or guitar could be had and their touring schedules would allow. When Elvis died, James openly wept over his casket saying, “What did they do to you, Elvis…what did they do?”

But this isn’t about Elvis, it’s about a man that was his equal as a performer and musician—maybe more so.

Brown’s influence is so pervasive that it can be heard well beyond the boundaries of R&B. When a jazz musician lays down a groove on a dominant chord with a heavily syncopated beat in a certain way, you’re hearing James. “Funk” that peculiar strain of R&B is also “James Brown Music,” which is what we used to call it. If words failed to adequately describe a musician's meaning, they could invoke Brown's name and everybody instantly knew what to do. In fact, almost any groove-based music after the late sixties, maybe the early seventies, is similarly indebted.

Without James there would be no funk, not as we generally think of it, at least. Some talk about Bootsy Collins or George Clinton as co-founders of the music, the three as equals in terms of significance. Nonsense! Bootsy got his start in Brown's band. Both Collins and Clinton were interpreters of the music that Brown created, long before either came on the scene.

You can also hear Brown's influence in Gospel and rock. I’m sure there are plenty of country musicians, who, when no one is listening (save their fellow musicians) pay homage as well.

James Brown created his music out of a disparate range of influences; Little Willie John, the R&B pioneer, whose song “Fever” was recorded by everybody from Elvis to Miss Peggy Lee, was an influence. So were other pre-soul performers like Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, Little Richard and Billy Ward and the Dominoes. They formed the basis of his style in the early years as a performer.

Church music was at the root of it all, as it was for so many Southern performers, especially black artists, who never strayed far from that unique blend of gospel and blues—those twin sons of different fathers—one born in juke joints on Saturday nights and the other in churches on Sunday mornings. They represented the Africanized rhythms and European melodic and harmonic traditions that became an indelible part of American culture. A sound that emerged from a hostile world, but still managed to feel like home.

James developed what became his signature sound after hearing Miles’ Davis seminal “Kind of Blue.” Miles’ new approach lacked traditional harmonic structure and was based on one and two chord vamps. This inspired James to follow a similar path. His band would groove on one chord, with a modally derived bass and guitar riff that worked off the drums like a grooving, syncopated machine—sometimes with no bridge, no traditional AABA song-form and no story-based lyric. The lyrics were created, like the music, for their rhythmic quality. It was a move towards music that was essentially pure rhythm. James adaptation of Miles’ innovation was so completely absorbed that its source material was almost unrecognizable.

Both men were looking for the same thing, freedom. James used his band like a drum, while Miles was interested in wide-open spaces that enabled him to improvise inside and out of the songs’ harmonic framework. He took the traditions that had been established generations earlier by the blues, Broadway and Tin Pan Alley and reduced them to an essence. In his own way, James pushed that concept even further.

The two men were fast friends, singing gospel music in their off hours--in hotel rooms, or wherever a piano or guitar could be had and their touring schedules would allow. When Elvis died, James openly wept over his casket saying, “What did they do to you, Elvis…what did they do?”

But this isn’t about Elvis, it’s about a man that was his equal as a performer and musician—maybe more so.

Brown’s influence is so pervasive that it can be heard well beyond the boundaries of R&B. When a jazz musician lays down a groove on a dominant chord with a heavily syncopated beat in a certain way, you’re hearing James. “Funk” that peculiar strain of R&B is also “James Brown Music,” which is what we used to call it. If words failed to adequately describe a musician's meaning, they could invoke Brown's name and everybody instantly knew what to do. In fact, almost any groove-based music after the late sixties, maybe the early seventies, is similarly indebted.

Without James there would be no funk, not as we generally think of it, at least. Some talk about Bootsy Collins or George Clinton as co-founders of the music, the three as equals in terms of significance. Nonsense! Bootsy got his start in Brown's band. Both Collins and Clinton were interpreters of the music that Brown created, long before either came on the scene.

You can also hear Brown's influence in Gospel and rock. I’m sure there are plenty of country musicians, who, when no one is listening (save their fellow musicians) pay homage as well.

James Brown created his music out of a disparate range of influences; Little Willie John, the R&B pioneer, whose song “Fever” was recorded by everybody from Elvis to Miss Peggy Lee, was an influence. So were other pre-soul performers like Hank Ballard and the Midnighters, Little Richard and Billy Ward and the Dominoes. They formed the basis of his style in the early years as a performer.

Church music was at the root of it all, as it was for so many Southern performers, especially black artists, who never strayed far from that unique blend of gospel and blues—those twin sons of different fathers—one born in juke joints on Saturday nights and the other in churches on Sunday mornings. They represented the Africanized rhythms and European melodic and harmonic traditions that became an indelible part of American culture. A sound that emerged from a hostile world, but still managed to feel like home.

James developed what became his signature sound after hearing Miles’ Davis seminal “Kind of Blue.” Miles’ new approach lacked traditional harmonic structure and was based on one and two chord vamps. This inspired James to follow a similar path. His band would groove on one chord, with a modally derived bass and guitar riff that worked off the drums like a grooving, syncopated machine—sometimes with no bridge, no traditional AABA song-form and no story-based lyric. The lyrics were created, like the music, for their rhythmic quality. It was a move towards music that was essentially pure rhythm. James adaptation of Miles’ innovation was so completely absorbed that its source material was almost unrecognizable.

Both men were looking for the same thing, freedom. James used his band like a drum, while Miles was interested in wide-open spaces that enabled him to improvise inside and out of the songs’ harmonic framework. He took the traditions that had been established generations earlier by the blues, Broadway and Tin Pan Alley and reduced them to an essence. In his own way, James pushed that concept even further.

That Brown heard the possibilities in Miles’ music for his own is a testament to his musical intelligence and curiosity. He had a studious need to listen to everything and anything for utilitarian ideas. Ideas that, often, existed well outside the normal boundaries that had been in place since the earliest days of blues and gospel. Even before R&B became its own unique style.

Davis, years later, would repay the debt with his electric bands. Bitches Brew being a good example of his Sly Stone (a Brown acolyte) meets Jimi Hendrix (another debtor) blending of free-jazz and modal-funk, ultimately called “Fusion Music.”

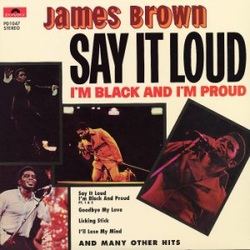

James was a political activist and coined the phrase “Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud” at a time when the civil rights movement was still struggling to get a foothold. It became a slogan of solidarity and identity enabling African Americans to see themselves as something more than Negroes and second-class citizens. This was before rights had been won, when speaking out could mean the end of your career. It was, in some ways, easier for Brown because his audience was substantially black and, therefore, less visible to the mainstream. But, it could have just as easily stalled his career, relegating it for the duration to the chitlin’-circuit.

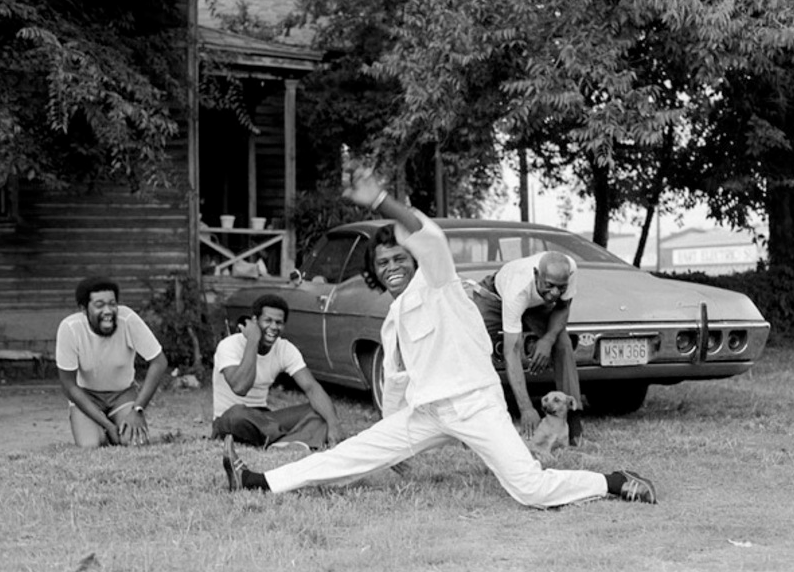

His performance on “The T.A.M.I. Show was a watershed moment for black and white fans alike. I can remember seeing the movie when I was ten years old, in 1964, the year the movie came out. Brown was almost freakish in his moves and rhythms, at least, that’s the way it seemed to me. I mean that in the best possible way. It was shocking, almost frightening, probably because I had no way as a kid to contextualize what I was seeing. By comparison, The Rolling Stones came across like a bunch of well-scrubbed teenage street-junkies. Not exactly what you’d expect, but close enough. Their music was an extension of what had already happened with Chuck Berry and American rock & roll a decade earlier. Berry also happened to be on the show and gave his own galvanizing performance. Mick Jagger’s dance moves, when contrasted with Browns’, were almost self-consciously spastic. That might have been a good thing, if for no other reason than that it took the heat off of him to really toe the mark.

There are so many ways in which James influenced the culture, dance being another. Michael Jackson was a tiny James Brown wanna-be in his early years and never really strayed too far from the master’s methodology. Prince took the same path. Succeeding generations of would-be R&B messiahs have never deviated too far from his design.

Either way, James is there—heard and seen with every syncopated drop of the snare drum. In every syncopated horn line that accents the beat. In every move of the dancers’ shuffle or the perfectly-timed split, you see the former shoeshine boy and boxer working the crowd on some Georgia street corner, just like he did as a tough street kid—taking the various art forms to new levels of athletic and aesthetic accomplishment.

In the mid-1980s, James had a career resurgence, as did sixties soul music in general. His song “Living in America” hit it big as a part of one of the endless “Rocky” sequels. Baby boomers were looking back as they approached midlife, searching for their past. It was in this context that I had the good fortune to see James paired with another sixties icon, Wilson Pickett at a club on Miami Beach for an audience of maybe a thousand people. The intimate setting provided an up close and personal concert with good sound. Wilson opened the show and was still, two decades after “The Midnight Hour” hit the charts, a potent performer. His band was tight and what you hope for when hearing a first-rate R&B group. Every night after the show was over another legend would come down to jam. Willie Nelson was playing at the Local Flea Market, with a circus as his opening act. Being an inveterate, any time, any place jammer, Willie went looking for a place to play and found it with Wilson’s band. Such is the nature of real musicians who couldn't care less about marketable categories once the bills have been paid.

James Brown, “Mr. Dynamite,” “The Godfather of Soul,” whatever title you choose, closed the show and performed like it was 1962—even if the splits were fewer in number. The music, the man and the band were a powerhouse, mirroring his relentless drive for perfection without predictability. Remarkable, considering his journey began more than three decades before.

Years later, after his wife had died and he’d spent time in prison for income tax evasion, after he had become something of a cultural caricature, the great man slowly faded from sight. He was remembered by some as a musical prophet and a political force, with a potent soundtrack that could mesmerize a crowd. For others, he was a memory of a memory, a family artifact like an old photograph or album cover. But for much of the world, especially among musicians, there is only one James Brown. Just like there is only one Ray Charles, Johnny Cash or Einstein, for that matter.

Who was James Brown, really? He was a genius of a type, that's for certain. But, as is the case with most radical public figures, there is no simple answer. If you've lived your life on the public stage, those lines inevitably blur and assimilate. Thinking back to the concert thirty years earlier, I can remember seeing Butane James in a crowded lobby before the show, talking intently to a young white man. He spoke openly to him, like no one else was around, offering a gospel tract and his personal and very hard-won wisdom about God and life. The young man seemed to be lost and James, rather than hurrying him along, appeared to actually care. Brown was short, stocky and still powerfully built, in spite of the fact that he was probably at least fifty and a veteran of a long showbiz life. In that moment, it wasn't the up-coming concert that seemed important to him, but the kid standing in front of him. That's how I choose to remember James Brown, as gritty and real as life—just like his music.

Mark Magula

Davis, years later, would repay the debt with his electric bands. Bitches Brew being a good example of his Sly Stone (a Brown acolyte) meets Jimi Hendrix (another debtor) blending of free-jazz and modal-funk, ultimately called “Fusion Music.”

James was a political activist and coined the phrase “Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud” at a time when the civil rights movement was still struggling to get a foothold. It became a slogan of solidarity and identity enabling African Americans to see themselves as something more than Negroes and second-class citizens. This was before rights had been won, when speaking out could mean the end of your career. It was, in some ways, easier for Brown because his audience was substantially black and, therefore, less visible to the mainstream. But, it could have just as easily stalled his career, relegating it for the duration to the chitlin’-circuit.

His performance on “The T.A.M.I. Show was a watershed moment for black and white fans alike. I can remember seeing the movie when I was ten years old, in 1964, the year the movie came out. Brown was almost freakish in his moves and rhythms, at least, that’s the way it seemed to me. I mean that in the best possible way. It was shocking, almost frightening, probably because I had no way as a kid to contextualize what I was seeing. By comparison, The Rolling Stones came across like a bunch of well-scrubbed teenage street-junkies. Not exactly what you’d expect, but close enough. Their music was an extension of what had already happened with Chuck Berry and American rock & roll a decade earlier. Berry also happened to be on the show and gave his own galvanizing performance. Mick Jagger’s dance moves, when contrasted with Browns’, were almost self-consciously spastic. That might have been a good thing, if for no other reason than that it took the heat off of him to really toe the mark.

There are so many ways in which James influenced the culture, dance being another. Michael Jackson was a tiny James Brown wanna-be in his early years and never really strayed too far from the master’s methodology. Prince took the same path. Succeeding generations of would-be R&B messiahs have never deviated too far from his design.

Either way, James is there—heard and seen with every syncopated drop of the snare drum. In every syncopated horn line that accents the beat. In every move of the dancers’ shuffle or the perfectly-timed split, you see the former shoeshine boy and boxer working the crowd on some Georgia street corner, just like he did as a tough street kid—taking the various art forms to new levels of athletic and aesthetic accomplishment.

In the mid-1980s, James had a career resurgence, as did sixties soul music in general. His song “Living in America” hit it big as a part of one of the endless “Rocky” sequels. Baby boomers were looking back as they approached midlife, searching for their past. It was in this context that I had the good fortune to see James paired with another sixties icon, Wilson Pickett at a club on Miami Beach for an audience of maybe a thousand people. The intimate setting provided an up close and personal concert with good sound. Wilson opened the show and was still, two decades after “The Midnight Hour” hit the charts, a potent performer. His band was tight and what you hope for when hearing a first-rate R&B group. Every night after the show was over another legend would come down to jam. Willie Nelson was playing at the Local Flea Market, with a circus as his opening act. Being an inveterate, any time, any place jammer, Willie went looking for a place to play and found it with Wilson’s band. Such is the nature of real musicians who couldn't care less about marketable categories once the bills have been paid.

James Brown, “Mr. Dynamite,” “The Godfather of Soul,” whatever title you choose, closed the show and performed like it was 1962—even if the splits were fewer in number. The music, the man and the band were a powerhouse, mirroring his relentless drive for perfection without predictability. Remarkable, considering his journey began more than three decades before.

Years later, after his wife had died and he’d spent time in prison for income tax evasion, after he had become something of a cultural caricature, the great man slowly faded from sight. He was remembered by some as a musical prophet and a political force, with a potent soundtrack that could mesmerize a crowd. For others, he was a memory of a memory, a family artifact like an old photograph or album cover. But for much of the world, especially among musicians, there is only one James Brown. Just like there is only one Ray Charles, Johnny Cash or Einstein, for that matter.

Who was James Brown, really? He was a genius of a type, that's for certain. But, as is the case with most radical public figures, there is no simple answer. If you've lived your life on the public stage, those lines inevitably blur and assimilate. Thinking back to the concert thirty years earlier, I can remember seeing Butane James in a crowded lobby before the show, talking intently to a young white man. He spoke openly to him, like no one else was around, offering a gospel tract and his personal and very hard-won wisdom about God and life. The young man seemed to be lost and James, rather than hurrying him along, appeared to actually care. Brown was short, stocky and still powerfully built, in spite of the fact that he was probably at least fifty and a veteran of a long showbiz life. In that moment, it wasn't the up-coming concert that seemed important to him, but the kid standing in front of him. That's how I choose to remember James Brown, as gritty and real as life—just like his music.

Mark Magula