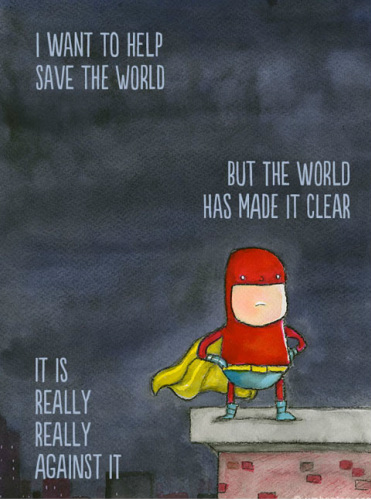

How Can we Save the World from People who want to Save the World?

There appears to be a need in some people to save the world. Exactly why they think this way is hard to know, except in some broadly-defined sense. Perhaps, at it's core, it reflects a tendency to view the world through the very narrow lens of our time, reducing it even further to the much narrower lens of our personal experience. Once we recognize that the world is more complex than any one person's perspective, no matter how well that perspective may be researched, a little humility should ensue. But, frequently, the opposite happens. The self-reflective visionary needs only their own vision from which to infer—and their imagination will do the rest.

There are many ways to save the world, of course; from sin, that would be one way, the word “sin” covers a lot of territory. More specifically; global warming, racism, hunger and war would make any top ten list. Maybe, the greatest sin of all is willful ignorance—from this peculiar form of ignorance flows all the others. Throw in greed and you've pretty much covered everything.

Greed is hard to miss. It tries to hide behind words like: communism, socialism, capitalism, me, mine, us, we—greed, however, can be spotted without much effort, even if it's not so easy to see in ourselves.

Ignorance, on the other hand, can be disguised by lofty rhetoric and soaring oratory, appearing to reflect only our best wishes, making it virtually undetectable. It lurks, obscured by ideology, seen only at the long end of a chain of events, like a shark moving through the shadow of a wave.

It's frequently bolstered by belief and solidified by conviction, leading us to conclude that our intentions couldn't really be bad. Misguided maybe, but bad, that requires an act of will. And, believe me when I say, “I only desire to do good; therefore, whatever I do can't be bad.”

This reminds me of the would-be poet who defensively declares that they intended to say what they said. So, doesn't that at least make them honest, as though honesty and knowledge of craft were one and the same. Suddenly, the bad becomes good because of the goodness and honesty of their intentions. The actual artifact; the poem or song, the congressional bill or governmental mandate must also be good, because it came from people whose intentions were good. But life doesn't work like that.

If you drop a pebble in a pond it causes a ripple that travels outward from it's source, oscillating until it's energy is spent. It does this whether we want it to or not. For everything there is a cause and its effect. That's really what we're talking about. If you don't work, you don't eat; don't eat and you die! Die, and you rot and decay into earth and back from whence you came. It's unavoidable.

Ultimately, arrogance compels us to believe that by virtue of our virtuous intentions, we can undo natural law. That all bad things can be mediated, their effect sent backwards in time to it's zero moment, but nature is indifferent to human desire. From the ripple effect of something as simple as a pebble dropped in a pond, to the inevitable heat-death of our sun, there is no escape from this universal principle and its aftermath. There is no amount of cleverness that can release us from the responsibility to act cautiously, without caution there can be no virtue. The universe simply wasn't made that way—and the belief that we can force it to work differently may be the greatest sin of all.

Mark Magula

There are many ways to save the world, of course; from sin, that would be one way, the word “sin” covers a lot of territory. More specifically; global warming, racism, hunger and war would make any top ten list. Maybe, the greatest sin of all is willful ignorance—from this peculiar form of ignorance flows all the others. Throw in greed and you've pretty much covered everything.

Greed is hard to miss. It tries to hide behind words like: communism, socialism, capitalism, me, mine, us, we—greed, however, can be spotted without much effort, even if it's not so easy to see in ourselves.

Ignorance, on the other hand, can be disguised by lofty rhetoric and soaring oratory, appearing to reflect only our best wishes, making it virtually undetectable. It lurks, obscured by ideology, seen only at the long end of a chain of events, like a shark moving through the shadow of a wave.

It's frequently bolstered by belief and solidified by conviction, leading us to conclude that our intentions couldn't really be bad. Misguided maybe, but bad, that requires an act of will. And, believe me when I say, “I only desire to do good; therefore, whatever I do can't be bad.”

This reminds me of the would-be poet who defensively declares that they intended to say what they said. So, doesn't that at least make them honest, as though honesty and knowledge of craft were one and the same. Suddenly, the bad becomes good because of the goodness and honesty of their intentions. The actual artifact; the poem or song, the congressional bill or governmental mandate must also be good, because it came from people whose intentions were good. But life doesn't work like that.

If you drop a pebble in a pond it causes a ripple that travels outward from it's source, oscillating until it's energy is spent. It does this whether we want it to or not. For everything there is a cause and its effect. That's really what we're talking about. If you don't work, you don't eat; don't eat and you die! Die, and you rot and decay into earth and back from whence you came. It's unavoidable.

Ultimately, arrogance compels us to believe that by virtue of our virtuous intentions, we can undo natural law. That all bad things can be mediated, their effect sent backwards in time to it's zero moment, but nature is indifferent to human desire. From the ripple effect of something as simple as a pebble dropped in a pond, to the inevitable heat-death of our sun, there is no escape from this universal principle and its aftermath. There is no amount of cleverness that can release us from the responsibility to act cautiously, without caution there can be no virtue. The universe simply wasn't made that way—and the belief that we can force it to work differently may be the greatest sin of all.

Mark Magula