Hearing Duane Eddy

Hearing Duane Eddy

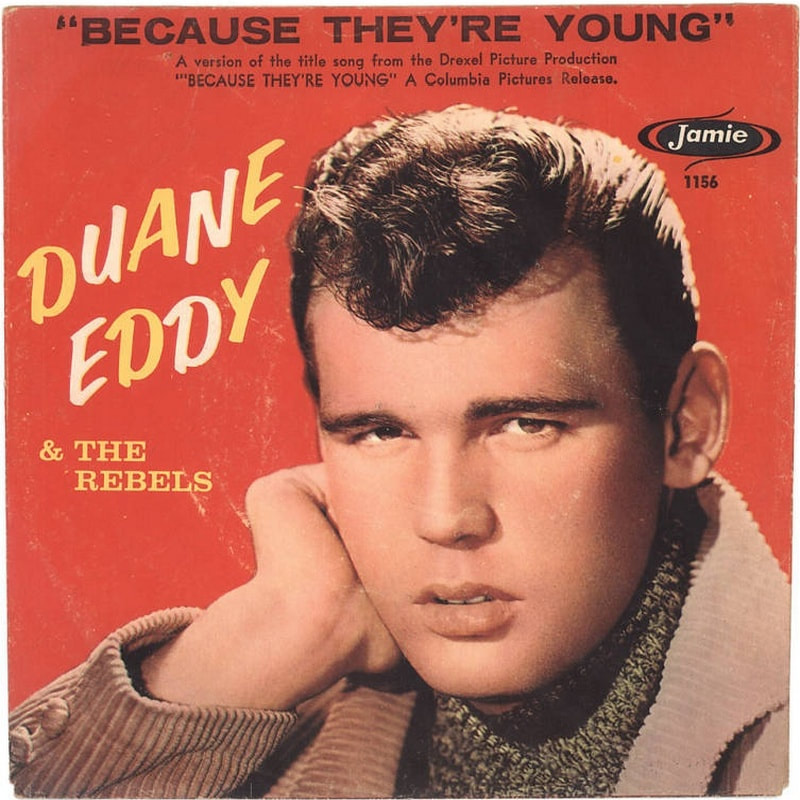

Music never sounds more beautiful, than when it’s barely heard. When it’s rare like a diamond, then, it’s value is almost immeasurable. I remember hearing Duane Eddy’s “Ramrod” sometime in the 1970’s, long after his heyday at the top of charts had passed. A small college radio station happened to play the song, otherwise, there was nothing else like it on the radio, or TV, or the movies. You couldn’t even find his music in most record stores. So, if you wanted to hear Duane Eddy, in any context, you were out of luck.

This was equally true of a host of blues artists like Buddy Guy, who, today, is an icon. But then, Guy was a forgotten man. Under the best of circumstances, though, Buddy was a little-known commodity, in spite of the fact that he’d been a major influence on Hendrix, Clapton, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, as well as pretty much a whole generation of White rockers, who’d made a financial killing out of playing blues-based music for a younger, White audience. Meaning, if I wanted to hear Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, T Bone Walker, Muddy Waters, or Duane Eddy, I was dead out-of-luck. Which is why hearing “Ramrod”, on that day, went through my body like an electrical charge.

Remarkably, later that same afternoon, I happened to stop at a local thrift store, and lo and behold, there it was, a modestly playable Duane Eddy album from 1957, including the song Ramrod. When cleaned up, the scratches were almost inaudible. But even if I could hear them, it still sounded like a long, cool breeze on a hot summer’s day, far better than any remastered CD or Mp3 version of that record sounds today.

What made it sound so good? That was simple. It was scarce, almost unattainable, except for my good fortune in the local thrift store.

I amassed a sizable jazz, blues and early rock and roll collection, using the same method, finding records whenever and wherever I could. When I found them, they sounded far sweeter and more exotic than they do today, when all of this music (and more) is available at my fingertips and costs nothing to hear, whenever I want, as much as I want. Simply put, the value of anything is based on two factors, its availability and its desirability. If any commodity is rare and highly desirable, its value will soar, simply because people will pay more to get it, driving its price higher. This is true of houses, cars, paintings, food, even medicine. But, in a free and open market, that same desirability will drive entrepreneurs to find ways to make it available, leading us to where we are today, a market where it’s all accessible—for damned near nothing—and, in abundance. That’s how and why we live in a culture where “The Poor” are just as likely to suffer from obesity as the rich. Freedom produces prosperity.

Still, I miss the days when music was a rare and beautiful thing. If for no other reason than the thrill of the hunt. But, also, because of the way the music sounds when it isn’t as common as dirt, overplayed, over-marketed, and supersaturated. It is this strange dichotomy in human nature that assigns value, but more importantly, offers intense pleasure in want. “Want,” becomes preeminent, once our needs are met, and we live in the first society in human history, which has been so successful at providing our needs, that the two are confused as one and the same. How we came to this place, should be studied endlessly. And is, but only by a rare few, who understand just how scarce such a society tends to be—and, just how desirable it is for people who live elsewhere. The rest of us take it for granted, as we do with the music, the food, the new cars, and everything else that exists in such over-abundance. That’s America. A shining city on a hill, as perfectly realized as a deeply imperfect species can hope for.

Mak Magula

Music never sounds more beautiful, than when it’s barely heard. When it’s rare like a diamond, then, it’s value is almost immeasurable. I remember hearing Duane Eddy’s “Ramrod” sometime in the 1970’s, long after his heyday at the top of charts had passed. A small college radio station happened to play the song, otherwise, there was nothing else like it on the radio, or TV, or the movies. You couldn’t even find his music in most record stores. So, if you wanted to hear Duane Eddy, in any context, you were out of luck.

This was equally true of a host of blues artists like Buddy Guy, who, today, is an icon. But then, Guy was a forgotten man. Under the best of circumstances, though, Buddy was a little-known commodity, in spite of the fact that he’d been a major influence on Hendrix, Clapton, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, as well as pretty much a whole generation of White rockers, who’d made a financial killing out of playing blues-based music for a younger, White audience. Meaning, if I wanted to hear Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, T Bone Walker, Muddy Waters, or Duane Eddy, I was dead out-of-luck. Which is why hearing “Ramrod”, on that day, went through my body like an electrical charge.

Remarkably, later that same afternoon, I happened to stop at a local thrift store, and lo and behold, there it was, a modestly playable Duane Eddy album from 1957, including the song Ramrod. When cleaned up, the scratches were almost inaudible. But even if I could hear them, it still sounded like a long, cool breeze on a hot summer’s day, far better than any remastered CD or Mp3 version of that record sounds today.

What made it sound so good? That was simple. It was scarce, almost unattainable, except for my good fortune in the local thrift store.

I amassed a sizable jazz, blues and early rock and roll collection, using the same method, finding records whenever and wherever I could. When I found them, they sounded far sweeter and more exotic than they do today, when all of this music (and more) is available at my fingertips and costs nothing to hear, whenever I want, as much as I want. Simply put, the value of anything is based on two factors, its availability and its desirability. If any commodity is rare and highly desirable, its value will soar, simply because people will pay more to get it, driving its price higher. This is true of houses, cars, paintings, food, even medicine. But, in a free and open market, that same desirability will drive entrepreneurs to find ways to make it available, leading us to where we are today, a market where it’s all accessible—for damned near nothing—and, in abundance. That’s how and why we live in a culture where “The Poor” are just as likely to suffer from obesity as the rich. Freedom produces prosperity.

Still, I miss the days when music was a rare and beautiful thing. If for no other reason than the thrill of the hunt. But, also, because of the way the music sounds when it isn’t as common as dirt, overplayed, over-marketed, and supersaturated. It is this strange dichotomy in human nature that assigns value, but more importantly, offers intense pleasure in want. “Want,” becomes preeminent, once our needs are met, and we live in the first society in human history, which has been so successful at providing our needs, that the two are confused as one and the same. How we came to this place, should be studied endlessly. And is, but only by a rare few, who understand just how scarce such a society tends to be—and, just how desirable it is for people who live elsewhere. The rest of us take it for granted, as we do with the music, the food, the new cars, and everything else that exists in such over-abundance. That’s America. A shining city on a hill, as perfectly realized as a deeply imperfect species can hope for.

Mak Magula