For The Love of Krazy Kat

What do Bix Beiderbecke, Jack Kerouac, Pablo Picasso, E.E. Cummings, William Randolph Hearst and Jules Feiffer have in common? They all loved Krazy Kat!

Seldom has a cartoon endured for so long, been so ignored by the public at large, and yet engendered so much affection by intellectuals and artists from such a range of disciplines.

Krazy Kat was possibly the first American transgender cartoon—an early homage to a sexual revolution in the making—one that predated the sexual awakenings of the 1920's, and fifty years before the sexual revolution of the 1960's.

On the other hand, that might just be a lot of pseudo-intellectual nonsense! Culturally, we seem to have a need to justify our tastes for fear of being considered too low-brow to simply enjoy a comic strip.

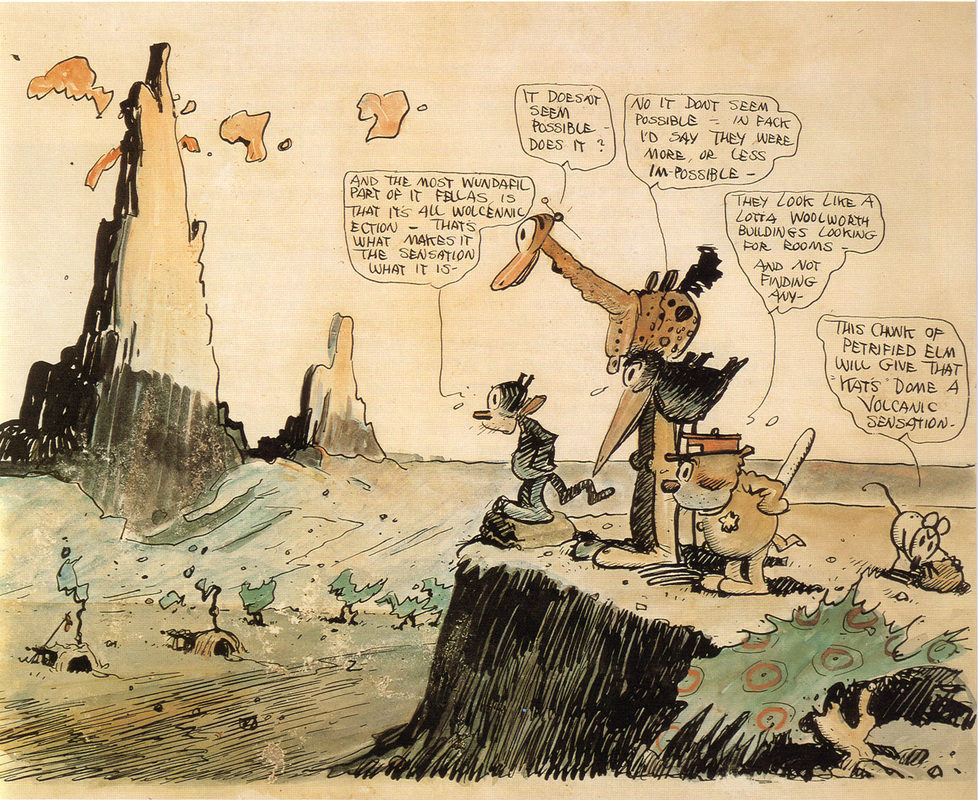

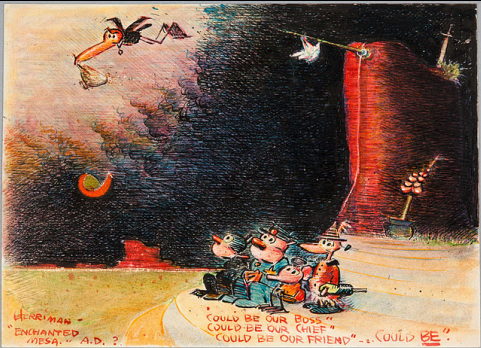

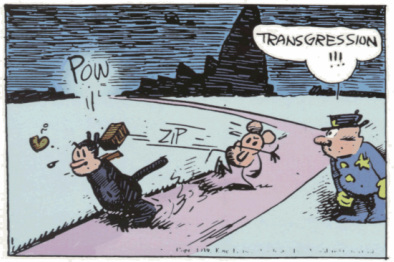

Krazy Kat was a beautifully illustrated, witty, lark of a cartoon, infused with its own ridiculous language and logic, with one simple reoccurring premise. Krazy, a simple-minded cat of ambiguous gender is in love with Ignatz the mouse. Ignatz spurns Krazy's advances and then conspires to launch a brick to Krazy's head in retaliation. Officer Pupp, the third part of the bizarre love triangle tries to foil Ignatz's plans by arresting him and putting him in jail, thereby saving Krazy from harm—while simultaneously hoping to earn Krazy Kat’s affections. The strip never got much more complex than that. It was the wonderfully expressive art and the absurd lengths that Ignatz would go to in retaliation that made it work. This bizarre brand of alternative reality was richly detailed in the vibrant artistic vision of its creator George Herriman.

Seldom has a cartoon endured for so long, been so ignored by the public at large, and yet engendered so much affection by intellectuals and artists from such a range of disciplines.

Krazy Kat was possibly the first American transgender cartoon—an early homage to a sexual revolution in the making—one that predated the sexual awakenings of the 1920's, and fifty years before the sexual revolution of the 1960's.

On the other hand, that might just be a lot of pseudo-intellectual nonsense! Culturally, we seem to have a need to justify our tastes for fear of being considered too low-brow to simply enjoy a comic strip.

Krazy Kat was a beautifully illustrated, witty, lark of a cartoon, infused with its own ridiculous language and logic, with one simple reoccurring premise. Krazy, a simple-minded cat of ambiguous gender is in love with Ignatz the mouse. Ignatz spurns Krazy's advances and then conspires to launch a brick to Krazy's head in retaliation. Officer Pupp, the third part of the bizarre love triangle tries to foil Ignatz's plans by arresting him and putting him in jail, thereby saving Krazy from harm—while simultaneously hoping to earn Krazy Kat’s affections. The strip never got much more complex than that. It was the wonderfully expressive art and the absurd lengths that Ignatz would go to in retaliation that made it work. This bizarre brand of alternative reality was richly detailed in the vibrant artistic vision of its creator George Herriman.

George Joseph Herriman was born in New Orleans, Louisiana on August 22, 1880. At ffteen, he was already selling cartoons that were syndicated around the U.S. His work was a unique blend of cutting-edge slapstick that was informed by a kind of metaphysical silliness that did what all great humor and art should do, it defied people’s expectations and offered a peculiar vision of the world as only Herriman saw it.

He created an anthropomorphic world of talking animals and surreal landscapes; using shadow and light, color and character the way a set designer or cinematographer might, decades in advance of the emerging technology. Artists like Herriman laid the ground rules for film animators like those at Disney and Warner Bros—with his creation becoming the subject of early film animation in 1916—works that only partially captured the essence of his strips.

There can be something uniquely powerful in a few frames of a cartoon, as in evidence in some of the pictures that accompany this article. Herriman created landscapes for his characters to move through that were evocative and spoke volumes about the world that they inhabited. Krazy Kat and his/her friends (Krazy Kat’s gender was sometimes referred to as she and at others as he) lived in a surreal version of Coconino County, Arizona, one that reflected the cultural influence of the Pueblo Indians in Herriman's art. As an additional comic device, he created a kind of homemade patois of Yiddish, Spanish and slang that gave depth and a wonderful element of the ridiculous to his creation.

Herriman's influence can easily be seen in later cartoons like the Roadrunner and Wiley Coyote or Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd. It may be that the combative relationships of cartoon tradition are really just a simple variation on the male-female archetypes with a peculiar twist. Fans and critics alike have interpreted the cartoon in the light of the surrealist artistic movements of the early twentieth century, such as Dadaism, which emerged at the same time as Krazy Kat.

He created an anthropomorphic world of talking animals and surreal landscapes; using shadow and light, color and character the way a set designer or cinematographer might, decades in advance of the emerging technology. Artists like Herriman laid the ground rules for film animators like those at Disney and Warner Bros—with his creation becoming the subject of early film animation in 1916—works that only partially captured the essence of his strips.

There can be something uniquely powerful in a few frames of a cartoon, as in evidence in some of the pictures that accompany this article. Herriman created landscapes for his characters to move through that were evocative and spoke volumes about the world that they inhabited. Krazy Kat and his/her friends (Krazy Kat’s gender was sometimes referred to as she and at others as he) lived in a surreal version of Coconino County, Arizona, one that reflected the cultural influence of the Pueblo Indians in Herriman's art. As an additional comic device, he created a kind of homemade patois of Yiddish, Spanish and slang that gave depth and a wonderful element of the ridiculous to his creation.

Herriman's influence can easily be seen in later cartoons like the Roadrunner and Wiley Coyote or Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd. It may be that the combative relationships of cartoon tradition are really just a simple variation on the male-female archetypes with a peculiar twist. Fans and critics alike have interpreted the cartoon in the light of the surrealist artistic movements of the early twentieth century, such as Dadaism, which emerged at the same time as Krazy Kat.

Dadaism was less an art form than a philosophical approach to painting, literature, poetry, the visual arts, journalism and politics—one that rejected the prevailing values of society and embraced the things that the culture thought of as insignificant. Dadaists were anti-war and anti-bourgeois, with an appreciation for the value of pop culture and the disaffected. Not surprisingly, it coincided with the emergence of various socialist movements that were in part a response to the extraordinary death toll and brutality of World War I. Women won the right to vote, there was the re-birth of political anarchism that was elevated in the public consciousness by the criminal trial of Sacco and Vanzetti, which was, at the time, considered to be the trial of the century. It was a period of great social upheaval in the arts, politics and in American life—as well as the rest of the world.

It wasn’t the first time that artists, poets and philosophers rejected the ideology of the ruling class and it wouldn’t be the last. From the French Revolution of the late seventeenth century to the early woman’s movement of the late nineteenth century to the Dadaists of the early twentieth century and on into the 1960s the pattern continues. War, social upheaval and rebellion are the feul for the new artistic and social movements that give expression to the cast-off and the outcast—and are alive and well in both the Tea Party and the Occupy Wall Street protestors.

It was in this social minefield that Krazy Kat was born and probably in part why it was one of the first comics to be widely praised by intellectuals and treated as "serious" art. Art critic Gilbert Seldes wrote a lengthy public speech about the strip in 1924, calling it "the most amusing, fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today.” Poet E.E. Cummings, another Herriman admirer, wrote the introduction to the first collection of the strip in book form. Other admirers included Pablo Picasso and Gertrude Stein.

Krazy Kat existed in many different incarnations, comic strip, film, as early as 1916 through the 1960’s, and beyond. But nothing is as compelling as Herriman’s original work on the funny pages. Even today, his creation survives as an inspiration to illustrators.

In 1995 Krazy, Ignatz and George Herriman were finally honored with their own stamp by the U.S. Post office.

While the cartoon was never more than modestly successful with American audiences, it has become a landmark for illustrators and art lovers the world over. It was voted by the Comics Journal as the best cartoon/comic book of the 20th century and continues to live on in the work of some of the finest cartoonist of the last hundred years.

It wasn’t the first time that artists, poets and philosophers rejected the ideology of the ruling class and it wouldn’t be the last. From the French Revolution of the late seventeenth century to the early woman’s movement of the late nineteenth century to the Dadaists of the early twentieth century and on into the 1960s the pattern continues. War, social upheaval and rebellion are the feul for the new artistic and social movements that give expression to the cast-off and the outcast—and are alive and well in both the Tea Party and the Occupy Wall Street protestors.

It was in this social minefield that Krazy Kat was born and probably in part why it was one of the first comics to be widely praised by intellectuals and treated as "serious" art. Art critic Gilbert Seldes wrote a lengthy public speech about the strip in 1924, calling it "the most amusing, fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today.” Poet E.E. Cummings, another Herriman admirer, wrote the introduction to the first collection of the strip in book form. Other admirers included Pablo Picasso and Gertrude Stein.

Krazy Kat existed in many different incarnations, comic strip, film, as early as 1916 through the 1960’s, and beyond. But nothing is as compelling as Herriman’s original work on the funny pages. Even today, his creation survives as an inspiration to illustrators.

In 1995 Krazy, Ignatz and George Herriman were finally honored with their own stamp by the U.S. Post office.

While the cartoon was never more than modestly successful with American audiences, it has become a landmark for illustrators and art lovers the world over. It was voted by the Comics Journal as the best cartoon/comic book of the 20th century and continues to live on in the work of some of the finest cartoonist of the last hundred years.

It may be that the best and earliest example of visual humor comes not from the slapstick comedians of the 1920’s or the 1930’s, like Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy or W.C. Fields, but from the artists who wrote and drew for the funny pages. Art, when it really is art, can either comment powerfully on its time or, as in the case of Herriman's best work, transcend it. It may also be that Krazy Kat, like all forms of personal expression, was inextricably linked to the broader culture from which they come, and that what seems, on first examination, like pseudo-intellectual nonsense, may not be as far-fetched as originally seen

Mark Magula

Mark Magula

|

|

|