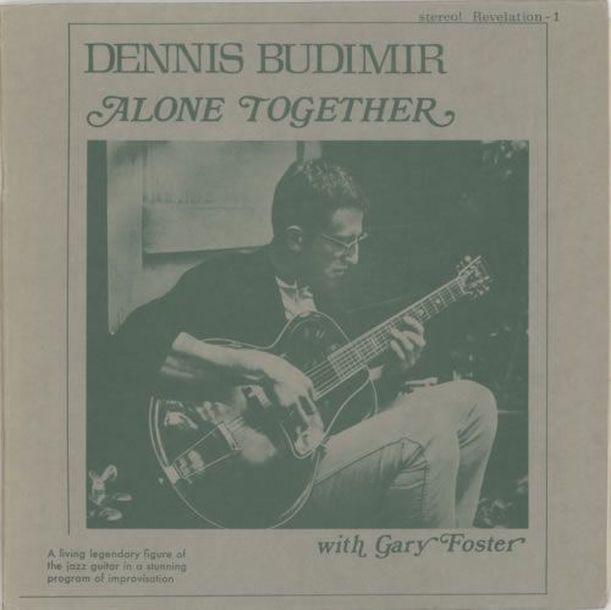

Dennis Budimir: Alone Together

Dennis Budimir’s “Alone Together” Revisited

Critics tend to make the same mistakes. Or, at least most do. They think that they’re supposed to be objective. And, they should try to be, when writing critically, regardless of the form. But part of the beauty of anything, no matter what, is that for you, its personnel. Like lust or love, individual preference, is that mysterious combination of memory, experience, and biology. What works for you, might not work the same for anyone else. Nor should it have to.

Right now I’m listening to an old jazz album “Alone Together” by guitarist Dennis Budimer, who was one of the legendary Wrecking Crew. That group of L.A. hotshot musicians who played on just about everybody’s records back in sixties and seventies. This album (yes, it’s an album) was recorded in 1964, prior to his entry into the L.A. recording scene.

Budimir had been a part Eric Dolphy’s band for a short period. That’s about as high up the food chain as you could get in the free jazz scene of the fifties and sixties. He was also among the first guitarist to play learn how to play “Outside.” In the jazz world, guitarist always seemed to catch on late, whether we’re talking about bebop, modal or free jazz. That eventually changed with the advent of “Fusion.” But that’s another story.

In Budimir’s case, his adaptability and considerable chops, the very things that made him a studio ace, also enabled him to call on a wide range of playing styles, making him a unique jazz stylist, as well. His fist album, recorded for the micro-label, Revelation records, was his take on the classic Bill Evans recording “Conversations with Myself,” featuring Evans playing a duet with himself through the magic of overdubbing. For the time, it was a fairly radical idea, since overdubbing was rare in an era of mostly mono recording. Budimir follows Evan’s lead and duets with himself, using the same process. He also performs with alto saxophonist Gary Foster, who appears on two cuts.

I have to admit, I'm a sucker for this kind of stripped to the bones fare, where musicians have little to hide behind beyond their talent. Budimir acquits himself well, as does Foster. In fact, the record sounds like they’re performing in someone’s living room, keeping it laid back and spare, while playing solely for themselves. In that sense, the music sounds timeless. Or, at least, comfortable in just about any era over the last 75 years. The liner notes by John William Hardy are effusive in their praise for Budimir’s willingness to break through the artificial restraints of the six string tradition and head for the outer limits, which he occasionally does.

Budimir’s playing is always personnel and inventive, never using his considerable chops as an excuse to play it safe, or to play hot and fast just because he can. You can hear him thinking as he negotiates the blues, using everything from raw, almost delta sounding blues licks, to the most modern of modern jazz ideas, all of which were rare for guitarists of the time. Kenny Burrell, like Budimir, was a session player on thousands of dates, playing everything from folk and rock to soul and bebop, but seldom ever had the opportunity to integrate these various forms into a single voice, as Budimir did. At least, that was the case on most of his jazz recordings, where niche markets tend to segregate musicians for the sake of marketing. Recording on a mom and pop label like Revelation--a label dedicated solely to great jazz--can have its benefits creatively, if not economically.

The album in question, “Alone Together” was recorded in 1964, the same year The Beatles broke in America, This was shortly after JFK’s assassination and about the time that Vietnam really became a national issue. James Bond was a new movie icon, then, while America, for all intents and purposes, was still mulling its way through the remainder of the 1950’s. Motown, like Stax and Muscle Shoals were new recording centers, as well. Limousine-sized cars with big fins were the style—and the 57 Chevy was as mean a car as you could find on the streets—while songs like “Its Judy’s Turn to Cry” exemplified teen life and love for a whole generation.

Meanwhile, Dennis Budimir sat and played inventive jazz and blues on an unamplified Gibson archtop, in complete contradiction to the newly emerging Brit-rock scene of the time. Whether alone or in duet, Budimir pointed the way to freedom for guitarist everywhere. It is a minor moment, in the scheme of things, musically speaking, but it was, and still is, a damn good jazz record.

For me, it's especially meaningful, probably because I first heard it at pivotal moment in my evolution as a musician. At the time, I knew nothing about Dennis Budimir or the music within, but bought it anyway, based primarily on the liner notes. That was one of the values of the LP, album art never looked so good and liner notes were easily readable. Solo jazz guitar was still a rare commodity then, which made it a more compelling way to hear the music, unencumbered by a band. After a few listens I was hooked, and thought, “One day, I’d like to be able to play like that.” Forty plus years and much woodshedding later, I can hold my own. Then, however, jazz was a revelation, just like the record label’s name suggests.

I hadn’t owned this particular record for many years. Ebay, however, gave it back to me. In damned near mint shape, too. After a relative few bucks spent, I once again was twenty years old and eager to learn this language called jazz, as I listened intently to this aging, but still very good LP, by one of jazz guitar's unsung heroes.

There is certainly a healthy measure of nostalgia mixed into my feelings. Which, for me, at least, makes experiencing the music deeper and more meaningful. It isn’t a response, pure and unsullied by bias. Personal bias, in this instance, is everywhere. Like love, it is an intimate mix of memory, emotion and familiarity.

With age, I've become musically more astute, by default, I guess. Meaning, I hear the music differently than I did then. However, I am pleased to find that what I hear, now, has genuine depth and invention, swing and joy, which is exactly what all good jazz should have. That was good enough, then. More than forty years later, it still is.

Mark Magula

Critics tend to make the same mistakes. Or, at least most do. They think that they’re supposed to be objective. And, they should try to be, when writing critically, regardless of the form. But part of the beauty of anything, no matter what, is that for you, its personnel. Like lust or love, individual preference, is that mysterious combination of memory, experience, and biology. What works for you, might not work the same for anyone else. Nor should it have to.

Right now I’m listening to an old jazz album “Alone Together” by guitarist Dennis Budimer, who was one of the legendary Wrecking Crew. That group of L.A. hotshot musicians who played on just about everybody’s records back in sixties and seventies. This album (yes, it’s an album) was recorded in 1964, prior to his entry into the L.A. recording scene.

Budimir had been a part Eric Dolphy’s band for a short period. That’s about as high up the food chain as you could get in the free jazz scene of the fifties and sixties. He was also among the first guitarist to play learn how to play “Outside.” In the jazz world, guitarist always seemed to catch on late, whether we’re talking about bebop, modal or free jazz. That eventually changed with the advent of “Fusion.” But that’s another story.

In Budimir’s case, his adaptability and considerable chops, the very things that made him a studio ace, also enabled him to call on a wide range of playing styles, making him a unique jazz stylist, as well. His fist album, recorded for the micro-label, Revelation records, was his take on the classic Bill Evans recording “Conversations with Myself,” featuring Evans playing a duet with himself through the magic of overdubbing. For the time, it was a fairly radical idea, since overdubbing was rare in an era of mostly mono recording. Budimir follows Evan’s lead and duets with himself, using the same process. He also performs with alto saxophonist Gary Foster, who appears on two cuts.

I have to admit, I'm a sucker for this kind of stripped to the bones fare, where musicians have little to hide behind beyond their talent. Budimir acquits himself well, as does Foster. In fact, the record sounds like they’re performing in someone’s living room, keeping it laid back and spare, while playing solely for themselves. In that sense, the music sounds timeless. Or, at least, comfortable in just about any era over the last 75 years. The liner notes by John William Hardy are effusive in their praise for Budimir’s willingness to break through the artificial restraints of the six string tradition and head for the outer limits, which he occasionally does.

Budimir’s playing is always personnel and inventive, never using his considerable chops as an excuse to play it safe, or to play hot and fast just because he can. You can hear him thinking as he negotiates the blues, using everything from raw, almost delta sounding blues licks, to the most modern of modern jazz ideas, all of which were rare for guitarists of the time. Kenny Burrell, like Budimir, was a session player on thousands of dates, playing everything from folk and rock to soul and bebop, but seldom ever had the opportunity to integrate these various forms into a single voice, as Budimir did. At least, that was the case on most of his jazz recordings, where niche markets tend to segregate musicians for the sake of marketing. Recording on a mom and pop label like Revelation--a label dedicated solely to great jazz--can have its benefits creatively, if not economically.

The album in question, “Alone Together” was recorded in 1964, the same year The Beatles broke in America, This was shortly after JFK’s assassination and about the time that Vietnam really became a national issue. James Bond was a new movie icon, then, while America, for all intents and purposes, was still mulling its way through the remainder of the 1950’s. Motown, like Stax and Muscle Shoals were new recording centers, as well. Limousine-sized cars with big fins were the style—and the 57 Chevy was as mean a car as you could find on the streets—while songs like “Its Judy’s Turn to Cry” exemplified teen life and love for a whole generation.

Meanwhile, Dennis Budimir sat and played inventive jazz and blues on an unamplified Gibson archtop, in complete contradiction to the newly emerging Brit-rock scene of the time. Whether alone or in duet, Budimir pointed the way to freedom for guitarist everywhere. It is a minor moment, in the scheme of things, musically speaking, but it was, and still is, a damn good jazz record.

For me, it's especially meaningful, probably because I first heard it at pivotal moment in my evolution as a musician. At the time, I knew nothing about Dennis Budimir or the music within, but bought it anyway, based primarily on the liner notes. That was one of the values of the LP, album art never looked so good and liner notes were easily readable. Solo jazz guitar was still a rare commodity then, which made it a more compelling way to hear the music, unencumbered by a band. After a few listens I was hooked, and thought, “One day, I’d like to be able to play like that.” Forty plus years and much woodshedding later, I can hold my own. Then, however, jazz was a revelation, just like the record label’s name suggests.

I hadn’t owned this particular record for many years. Ebay, however, gave it back to me. In damned near mint shape, too. After a relative few bucks spent, I once again was twenty years old and eager to learn this language called jazz, as I listened intently to this aging, but still very good LP, by one of jazz guitar's unsung heroes.

There is certainly a healthy measure of nostalgia mixed into my feelings. Which, for me, at least, makes experiencing the music deeper and more meaningful. It isn’t a response, pure and unsullied by bias. Personal bias, in this instance, is everywhere. Like love, it is an intimate mix of memory, emotion and familiarity.

With age, I've become musically more astute, by default, I guess. Meaning, I hear the music differently than I did then. However, I am pleased to find that what I hear, now, has genuine depth and invention, swing and joy, which is exactly what all good jazz should have. That was good enough, then. More than forty years later, it still is.

Mark Magula