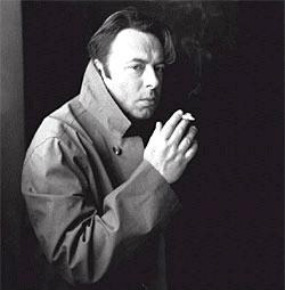

Christopher Hitchens - 4/13/49 - 12/15/11

"The essence of the independent mind lies not in what it thinks, but in how it thinks"

Christopher Hitchens recently died of Cancer—a horrible fate for any living thing. Not just for the rich and famous, those few whose profile is high enough to warrant public attention. Hitchens was a rhetorically gifted writer and speaker, with the kind of intellect seldom seen in a public persona. After all, who would be his audience? He found one nonetheless.

When I was a leftist Hitchens was one as well. His political views and my own shifted, and I found in his writing and public speaking a brilliant, sometimes arrogant and often times difficult man. He challenged his audience, fan and foe alike to think beyond the obvious—and what can be the self-righteous certainty of faith. He pushed forward, asking questions, willing to challenge the status quo politically, spiritually and in any other way that stood in the path of freedom as he understood it.

After the bombing of the World Trade Center in 2001, he boldly took on his old, leftist allies, moving ever so slightly to the right of the public debate—and without hesitation defended the war in Iraq, the Bush administration and Israel. For someone who considered himself a socialist/libertarian in the Chomsky mold, a writer for Vanity Fair among other much further-left-publications, it could have been suicidal. It didn’t matter. Hitchens followed his conscience and the evidence to their logical conclusion.

He probably entered the most public phase of his life after writing the book “God Is Not Great.” His take on the dark side of faith, targeting Mother Theresa, a woman as closely linked to sainthood as any living figure. In the process he exposed some of her less than saintly tendencies, relishing the opportunity to dismember her myth and by proxy, God as well.

When I was a leftist Hitchens was one as well. His political views and my own shifted, and I found in his writing and public speaking a brilliant, sometimes arrogant and often times difficult man. He challenged his audience, fan and foe alike to think beyond the obvious—and what can be the self-righteous certainty of faith. He pushed forward, asking questions, willing to challenge the status quo politically, spiritually and in any other way that stood in the path of freedom as he understood it.

After the bombing of the World Trade Center in 2001, he boldly took on his old, leftist allies, moving ever so slightly to the right of the public debate—and without hesitation defended the war in Iraq, the Bush administration and Israel. For someone who considered himself a socialist/libertarian in the Chomsky mold, a writer for Vanity Fair among other much further-left-publications, it could have been suicidal. It didn’t matter. Hitchens followed his conscience and the evidence to their logical conclusion.

He probably entered the most public phase of his life after writing the book “God Is Not Great.” His take on the dark side of faith, targeting Mother Theresa, a woman as closely linked to sainthood as any living figure. In the process he exposed some of her less than saintly tendencies, relishing the opportunity to dismember her myth and by proxy, God as well.

He publicly debated some of the finest Christian apologists and intellectuals, often on their own turf—fearlessly doing battle with scientists, philosophers and theologians—and in most instances more than held his own. If Hitchens didn’t win every battle, he frequently won the war, with an extraordinary gift for oratory, a mellifluous British-accented baritone speaking voice, and a wide-ranging and intimidating intellect sufficient to eviscerate even the most accomplished opponents.

If it sounds as though I’m in agreement with his view of God, I am not. We both, however, shared a loathing for the form religion often takes, as a kind of arrogant substitute for reason, with a tendency to view God in a way that most tyrants and serial killers would have trouble being associated with.

Hitchens referred to God as a celestial dictator, one that he would never acknowledge, let alone worship. He had a particular distaste for the Judeo-Christian God, who apparently, according to those in the know, demands worship or endless torture. I’m with him on that one. This is an odd thing for someone like me, who is a student of Jesus, whom I believe to be the embodiment of a very great God.

In the Woody Allen movie “Hannah and Her Sisters,” a painter, beautifully played by Max Von Sydow, says to his much younger lover “if Jesus saw what was being done in his name, he'd never stop throwing up!” I agree, I’m sure Christopher did as well.

Towards the end of his life, Hitchens became friends with Francis Collins, the man that headed the program that mapped the human genome—and who was a Christian. Collins attempted to find an alternative treatment for the lethal sickness that was killing Hitchens, a kindness that exemplifies Christ-likeness. Hitchens also acknowledged and thanked the many Christians who wrote and said that they were praying for him. For that I’m grateful.

It’s unfortunate that Hitchens was never presented with the Jesus of scripture, not the post-reformation, European Jesus that emerged about five hundred years ago, but, the first-century, Jewish radical, understood in his own culture, time and place. I think that they would have had much in common. Both were reformers, men of peace, unafraid to launch a rhetorical bomb at the smugly self-righteous, religious leaders of their time. I, frankly, will miss him, his marvelous wit, ferocious intelligence and deep commitment to the truth—wherever it might lead. Rest in peace!

Mark Magula

If it sounds as though I’m in agreement with his view of God, I am not. We both, however, shared a loathing for the form religion often takes, as a kind of arrogant substitute for reason, with a tendency to view God in a way that most tyrants and serial killers would have trouble being associated with.

Hitchens referred to God as a celestial dictator, one that he would never acknowledge, let alone worship. He had a particular distaste for the Judeo-Christian God, who apparently, according to those in the know, demands worship or endless torture. I’m with him on that one. This is an odd thing for someone like me, who is a student of Jesus, whom I believe to be the embodiment of a very great God.

In the Woody Allen movie “Hannah and Her Sisters,” a painter, beautifully played by Max Von Sydow, says to his much younger lover “if Jesus saw what was being done in his name, he'd never stop throwing up!” I agree, I’m sure Christopher did as well.

Towards the end of his life, Hitchens became friends with Francis Collins, the man that headed the program that mapped the human genome—and who was a Christian. Collins attempted to find an alternative treatment for the lethal sickness that was killing Hitchens, a kindness that exemplifies Christ-likeness. Hitchens also acknowledged and thanked the many Christians who wrote and said that they were praying for him. For that I’m grateful.

It’s unfortunate that Hitchens was never presented with the Jesus of scripture, not the post-reformation, European Jesus that emerged about five hundred years ago, but, the first-century, Jewish radical, understood in his own culture, time and place. I think that they would have had much in common. Both were reformers, men of peace, unafraid to launch a rhetorical bomb at the smugly self-righteous, religious leaders of their time. I, frankly, will miss him, his marvelous wit, ferocious intelligence and deep commitment to the truth—wherever it might lead. Rest in peace!

Mark Magula

|

|